To look back on any period of reading with the intention of selecting one’s favorite books is a curious two-way time machine — one must scoop the memory of a past and filter it through the sieve of an indefinite future in an effort to discern which books have left a mark on one’s conscience deep enough to last a lifetime. Of the many books I read in 2016, these are the sixteen that moved me most deeply and memorably. And since I stand with Susan Sontag, who

considered reading an act of rebirth, I invite you to revisit the annual favorites for

2015,

2014, and

2013.

“You are born alone. You die alone. The value of the space in between is trust and love,â€

“You are born alone. You die alone. The value of the space in between is trust and love,â€artist Louise Bourgeoise wrote in her diary at the end of a long and illustrious life as she contemplated

how solitude enriches creative work. It’s a lovely sentiment, but as empowering as it may be to those willing to embrace solitude, it can be tremendously lonesome-making to those for whom loneliness has contracted the space of trust and love into a suffocating penitentiary. For if in solitude, as Wendell Berry

memorably wrote, “one’s inner voices become audible [and] one responds more clearly to other lives,†in loneliness one’s inner scream becomes deafening, deadening, severing any thread of connection to other lives.

How to break free of that prison and reinhabit the space of trust and love is what

Olivia Laing explores in

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone (

public library) — an extraordinary more-than-memoir; a sort of memoir-plus-plus, partway between Helen MacDonald’s

H Is for Hawk and the diary of Virginia Woolf; a lyrical account of wading through a period of self-expatriation, both physical and psychological, in which Laing paints an intimate portrait of loneliness as “a populated place: a city in itself.â€

After the sudden collapse of a romance marked by extreme elation, Laing left her native England and took her shattered heart to New York, “that teeming island of gneiss and concrete and glass.†The daily, bone-deep loneliness she experienced there was both paralyzing in its all-consuming potency and, paradoxically, a strange invitation to aliveness. Indeed, her choice to leave home and wander a foreign city is itself a rich metaphor for the paradoxical nature of loneliness, animated by equal parts restlessness and stupor, capable of turning one into a voluntary vagabond and a catatonic recluse all at once, yet somehow a vitalizing laboratory for self-discovery. The pit of loneliness, she found, could “drive one to consider some of the larger questions of what it is to be alive.â€

She writes:

There were things that burned away at me, not only as a private individual, but also as a citizen of our century, our pixelated age. What does it mean to be lonely? How do we live, if we’re not intimately engaged with another human being? How do we connect with other people, particularly if we don’t find speaking easy? Is sex a cure for loneliness, and if it is, what happens if our body or sexuality is considered deviant or damaged, if we are ill or unblessed with beauty? And is technology helping with these things? Does it draw us closer together, or trap us behind screens?

Bedeviled by this acute emotional anguish, Laing seeks consolation in the great patron saints of loneliness in twentieth-century creative culture. From this eclectic tribe of the lonesome — including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Alfred Hitchcock, Peter Hujar, Billie Holiday, and Nan Goldin — Laing chooses four artists as her companions charting the terra incognita of loneliness: Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, Henry Darger, and David Wojnarowicz, who had all “grappled in their lives as well as work with loneliness and its attendant issues.â€

Laing examines the particular, pervasive form of loneliness in the eye of a city aswirl with humanity:

Imagine standing by a window at night, on the sixth or seventeenth or forty-third floor of a building. The city reveals itself as a set of cells, a hundred thousand windows, some darkened and some flooded with green or white or golden light. Inside, strangers swim to and fro, attending to the business of their private hours. You can see them, but you can’t reach them, and so this commonplace urban phenomenon, available in any city of the world on any night, conveys to even the most social a tremor of loneliness, its uneasy combination of separation and exposure.

You can be lonely anywhere, but there is a particular flavour to the loneliness that comes from living in a city, surrounded by millions of people. One might think this state was antithetical to urban living, to the massed presence of other human beings, and yet mere physical proximity is not enough to dispel a sense of internal isolation. It’s possible – easy, even – to feel desolate and unfrequented in oneself while living cheek by jowl with others. Cities can be lonely places, and in admitting this we see that loneliness doesn’t necessarily require physical solitude, but rather an absence or paucity of connection, closeness, kinship: an inability, for one reason or another, to find as much intimacy as is desired. Unhappy, as the dictionary has it, as a result of being without the companionship of others. Hardly any wonder, then, that it can reach its apotheosis in a crowd.

There is, of course, a universe of difference between solitude and loneliness — two radically different interior orientations toward the same exterior circumstance of lacking companionship. We speak of

“fertile solitude†as a developmental achievement essential for our creative capacity, but loneliness is barren and destructive; it cottons in apathy the will to create. More than that, it seems to signal an existential failing — a social stigma the nuances of which Laing addresses beautifully:

Loneliness is difficult to confess; difficult too to categorise. Like depression, a state with which it often intersects, it can run deep in the fabric of a person, as much a part of one’s being as laughing easily or having red hair. Then again, it can be transient, lapping in and out in reaction to external circumstance, like the loneliness that follows on the heels of a bereavement, break-up or change in social circles.

Like depression, like melancholy or restlessness, it is subject too to pathologisation, to being considered a disease. It has been said emphatically that loneliness serves no purpose… Perhaps I’m wrong, but I don’t think any experience so much a part of our common shared lives can be entirely devoid of meaning, without a richness and a value of some kind.

I’ve found no more lucid and luminous a defense of hope than the one

Rebecca Solnit launches in

Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities (

public library) — a slim, potent book that has grown only more relevant and poignant in the decade since its original publication in the wake of the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq, recently reissued with a new introduction by Solnit.

Rebecca Solnit (Photograph: Sallie Dean Shatz)

We lose hope, Solnit suggests, because we lose perspective — we lose sight of the “accretion of incremental, imperceptible changes†which constitute progress and which render our era dramatically different from the past, a contrast obscured by the undramatic nature of gradual transformation punctuated by occasional tumult. She writes:

There are times when it seems as though not only the future but the present is dark: few recognize what a radically transformed world we live in, one that has been transformed not only by such nightmares as global warming and global capital, but by dreams of freedom and of justice — and transformed by things we could not have dreamed of… We need to hope for the realization of our own dreams, but also to recognize a world that will remain wilder than our imaginations.

Solnit — one of the most singular, civically significant, and poetically potent voices of our time, emanating echoes of Virginia Woolf’s luminous prose and Adrienne Rich’s unflinching political conviction — looks back on the seemingly distant past as she peers forward into the near future:

The moment passed long ago, but despair, defeatism, cynicism, and the amnesia and assumptions from which they often arise have not dispersed, even as the most wildly, unimaginably magnificent things came to pass. There is a lot of evidence for the defense… Progressive, populist, and grassroots constituencies have had many victories. Popular power has continued to be a profound force for change. And the changes we’ve undergone, both wonderful and terrible, are astonishing.

[…]

This is an extraordinary time full of vital, transformative movements that could not be foreseen. It’s also a nightmarish time. Full engagement requires the ability to perceive both.

To read

Mary Oliver is to be read by her — to be made real by her words, to have the richest subterranean truths of your own experience mirrored back to you with tenfold the luminosity. Her prose collection

Upstream: Selected Essays (

public library) is a book of uncommon enchantment, containing Oliver’s largehearted wisdom on writing, creative work, and the art of life.

The working, concentrating artist is an adult who refuses interruption from himself, who remains absorbed and energized in and by the work — who is thus responsible to the work… Serious interruptions to work, therefore, are never the inopportune, cheerful, even loving interruptions which come to us from another.

[…]

It is six A.M., and I am working. I am absentminded, reckless, heedless of social obligations, etc. It is as it must be. The tire goes flat, the tooth falls out, there will be a hundred meals without mustard. The poem gets written. I have wrestled with the angel and I am stained with light and I have no shame. Neither do I have guilt. My responsibility is not to the ordinary, or the timely. It does not include mustard, or teeth. It does not extend to the lost button, or the beans in the pot. My loyalty is to the inner vision, whenever and howsoever it may arrive. If I have a meeting with you at three o’clock, rejoice if I am late. Rejoice even more if I do not arrive at all.

There is no other way work of artistic worth can be done. And the occasional success, to the striver, is worth everything. The most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave to it neither power nor time.

Everything we know about the universe so far comes from four centuries of sight — from peering into space with our eyes and their prosthetic extension, the telescope. Now commences a new mode of knowing the cosmos through sound. The detection of gravitational waves is one of the most significant discoveries in the entire history of physics, marking the dawn of a new era as we begin listening to the sound of space — the probable portal to mysteries as unimaginable to us today as galaxies and nebulae and pulsars and other cosmic wonders were to the first astronomers. Gravitational astronomy, as Levin elegantly puts it, promises a “score to accompany the silent movie humanity has compiled of the history of the universe from still images of the sky, a series of frozen snapshots captured over the past four hundred years since Galileo first pointed a crude telescope at the Sun.â€

Astonishingly enough, Levin wrote the book before the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) — the monumental instrument at the center of the story, decades in the making — made the actual detection of a ripple in the fabric of spacetime caused by the collision of two black holes in the autumn of 2015, exactly a century after Einstein first envisioned the possibility of gravitational waves. So the story she tells is not that of the triumph but that of the climb, which renders it all the more enchanting — because it is ultimately a story about the human spirit and its incredible tenacity, about why human beings choose to devote their entire lives to pursuits strewn with unimaginable obstacles and bedeviled by frequent failure, uncertain rewards, and meager public recognition.

Indeed, what makes the book interesting is that it tells the story of this monumental discovery, but what makes it enchanting is that Levin comes at it from a rather unusual perspective. She is a working astrophysicist who studies black holes, but she is also an

incredibly gifted novelist — an artist whose medium is language and thought itself. This is no popular science book but something many orders of magnitude higher in its artistic vision, the impeccable craftsmanship of language, and the sheer pleasure of the prose. The story is structured almost as a series of short, integrated novels, with each chapter devoted to one of the key scientists involved in LIGO. With Dostoyevskian insight and nuance, Levin paints a psychological, even philosophical portrait of each protagonist, revealing how intricately interwoven the genius and the foibles are in the fabric of personhood and what a profoundly human endeavor science ultimately is.

She writes:

Scientists are like those levers or knobs or those boulders helpfully screwed into a climbing wall. Like the wall is some cemented material made by mixing knowledge, which is a purely human construct, with reality, which we can only access through the filter of our minds. There’s an important pursuit of objectivity in science and nature and mathematics, but still the only way up the wall is through the individual people, and they come in specifics… So the climb is personal, a truly human endeavor, and the real expedition pixelates into individuals, not Platonic forms.

Gleick, who examined

the origin of our modern anxiety about time with remarkable prescience nearly two decades ago, traces the invention of the notion of time travel to H.G. Wells’s 1895 masterpiece

The Time Machine. Although Wells — like Gleick, like any reputable physicist — knew that time travel was a scientific impossibility, he created an aesthetic of thought which never previously existed and which has since shaped the modern consciousness. Gleick argues that the art this aesthetic produced — an entire canon of time travel literature and film — not only permeated popular culture but even influenced some of the greatest scientific minds of the past century, including

Stephen Hawking, who once cleverly hosted a party for time travelers and when no one showed up considered the impossibility of time travel proven, and

John Archibald Wheeler, who

popularized the term “black hole†and coined “wormhole,†both key tropes of time travel literature.

Gleick considers how a scientific impossibility can become such fertile ground for the artistic imagination:

Why do we need time travel, when we already travel through space so far and fast? For history. For mystery. For nostalgia. For hope. To examine our potential and explore our memories. To counter regret for the life we lived, the only life, one dimension, beginning to end.

Wells’s Time Machine revealed a turning in the road, an alteration in the human relationship with time. New technologies and ideas reinforced one another: the electric telegraph, the steam railroad, the earth science of Lyell and the life science of Darwin, the rise of archeology out of antiquarianism, and the perfection of clocks. When the nineteenth century turned to the twentieth, scientists and philosophers were primed to understand time in a new way. And so were we all. Time travel bloomed in the culture, its loops and twists and paradoxes.

I wrote about Gleick’s uncommonly pleasurable book at length

here.

THE VIEW FROM THE CHEAP SEATS

|

Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman is one of the most beloved storytellers of our time, unequaled at his singular brand of darkly delightful fantasy. His long-awaited nonfiction collection

The View from the Cheap Seats (

public library) celebrates a different side of Gaiman. Here stands a writer of firm conviction and porous curiosity, an idealist amid our morass of cynicism who, in revealing who he is, reveals who we are and who we can be if we only tried a little bit harder to wrest more goodness out of our imperfect humanity. An evangelist for the righteous without a shred of our culture’s pathological self-righteousness, Gaiman jolts us out of our collective amnesia and reminds us again and again what matters: ideas over ideologies, public libraries, the integrity of children’s inner lives, the stories we choose to tell of why the world is the way it is, the moral obligation to imagine better stories — and, oh, the sheer fun of it all.

I believe that it is difficult to kill an idea because ideas are invisible and contagious, and they move fast.

I believe that you can set your own ideas against ideas you dislike. That you should be free to argue, explain, clarify, debate, offend, insult, rage, mock, sing, dramatize, and deny.

I do not believe that burning, murdering, exploding people, smashing their heads with rocks (to let the bad ideas out), drowning them or even defeating them will work to contain ideas you do not like. Ideas spring up where you do not expect them, like weeds, and are as difficult to control.

I believe that repressing ideas spreads ideas.

“Memory is never a precise duplicate of the original… it is a continuing act of creation,â€

“Memory is never a precise duplicate of the original… it is a continuing act of creation,â€pioneering researcher Rosalind Cartwright wrote in distilling

the science of the unconscious mind.

Although I lack early childhood memories, I do have one rather eidetic recollection: I remember standing before the barren elephant yard at the Sofia Zoo in Bulgaria, at age three or so, clad in a cotton polka-dot jumper. I remember squinting into a scowl as the malnourished elephant behind me swirls dirt into the air in front of her communism-stamped concrete edifice. I don’t remember the temperature, though I deduce from the memory of my outfit that it must have been summer. I don’t remember the smell of the elephant or the touch of the blown dirt on my skin, though I remember my grimace.

For most of my life, I held onto that memory as the sole surviving mnemonic fragment of my early childhood self. And then, one day in my late twenties, I discovered an old photo album tucked into the back of my grandmother’s cabinet in Bulgaria. It contained dozens of photographs of me, from birth until around age four, including one depicting that very vignette — down to the minutest detail of what I believed was my memory of that moment. There I was, scowling in my polka-dot jumper with the elephant and the cloud of dust behind me. In an instant, I realized that I had been holding onto a prosthetic memory — what I remembered was the photograph from that day, which I must have been shown at some point, and not the day itself, of which I have no other recollection. The question — and what a Borgesian question — remains whether one should prefer having such a prosthetic memory, constructed entirely of photographs stitched together into artificial cohesion, to having no memory at all.

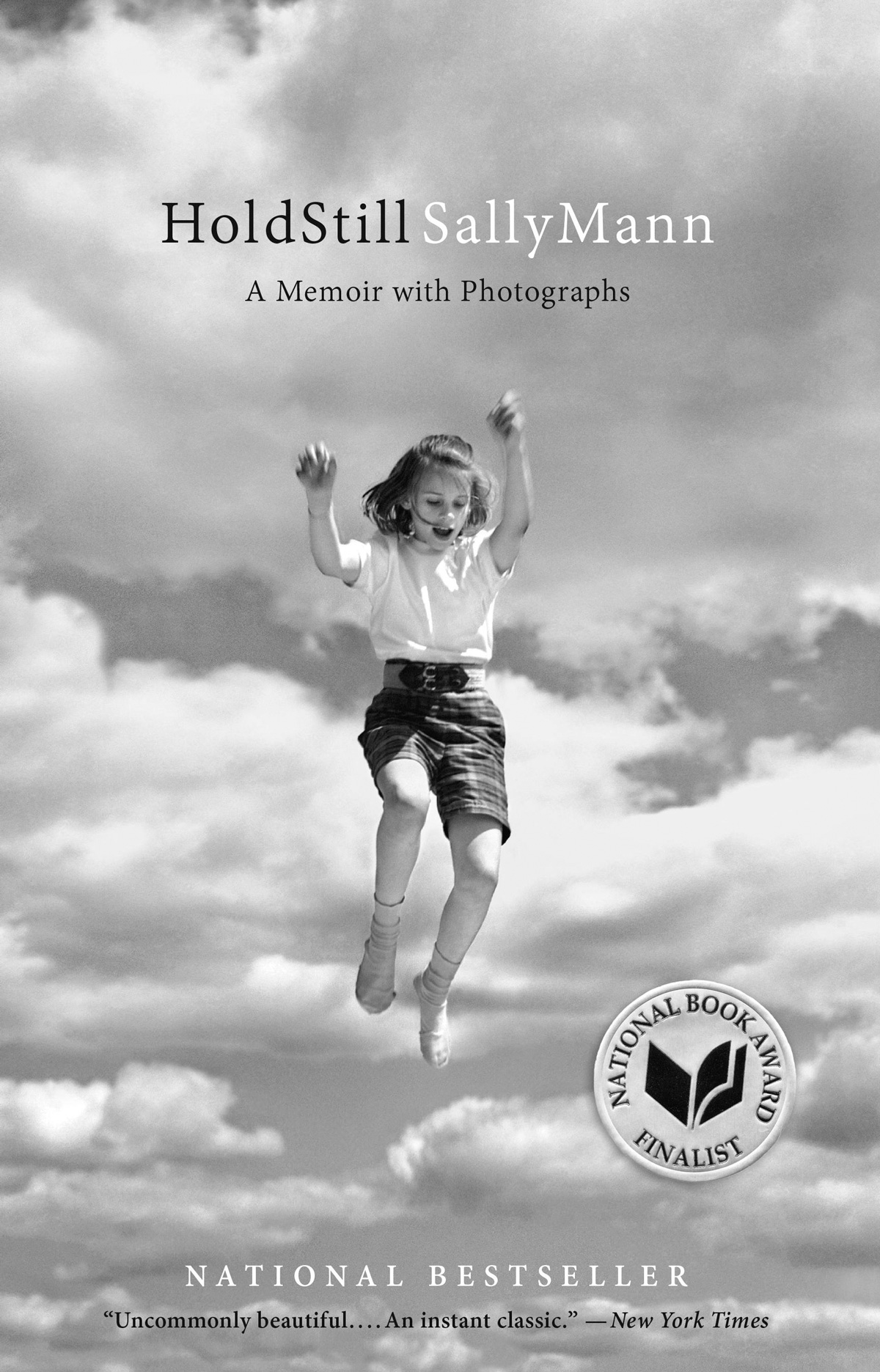

That confounding parallax of personal history is what photographer

Sally Mann explores throughout

Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs (

public library) — a lyrical yet unsentimental meditation on art, mortality, and the lacuna between memory and myth, undergirded by what Mann calls her “long preoccupation with the treachery of memory†and “memory’s truth, which is to scientific, objective truth as a pearl is to a piece of sand.â€

Sally Mann as a child

Whatever of my memories hadn’t crumbled into dust must surely by now have been altered by the passage of time. I tend to agree with the theory that if you want to keep a memory pristine, you must not call upon it too often, for each time it is revisited, you alter it irrevocably, remembering not the original impression left by experience but the last time you recalled it. With tiny differences creeping in at each cycle, the exercise of our memory does not bring us closer to the past but draws us farther away.

I had learned over time to meekly accept whatever betrayals memory pulled over on me, allowing my mind to polish its own beautiful lie. In distorting the information it’s supposed to be keeping safe, the brain, to its credit, will often bow to some instinctive aesthetic wisdom, imparting to our life’s events a coherence, logic, and symbolic elegance that’s not present or not so obvious in the improbable, disheveled sloppiness of what we’ve actually been through.

Photograph: Sally Mann

As far back as 1901 Émile Zola telegraphed the threat of this relatively new medium, remarking that you cannot claim to have really seen something until you have photographed it. What Zola perhaps also knew or intuited was that once photographed, whatever you had “really seen†would never be seen by the eye of memory again. It would forever be cut from the continuum of being, a mere sliver, a slight, translucent paring from the fat life of time; elegiac, one-dimensional, immediately assuming the amber quality of nostalgia: an instantaneous memento mori. Photography would seem to preserve our past and make it invulnerable to the distortions of repeated memorial superimpositions, but I think that is a fallacy: photographs supplant and corrupt the past, all the while creating their own memories. As I held my childhood pictures in my hands, in the tenderness of my “remembering,†I also knew that with each photograph I was forgetting.

Martha Nussbaum

Nussbaum, who has previously examined

the intelligence of the emotions and whom I consider the most incisive philosopher of our time, argues that despite anger’s long cultural history of being seen as morally justifiable and as a useful signal that wrongdoing has taken place, it is a normatively faulty response that masks deeper, more difficult emotions and stands in the way of resolving them. Consequently, forgiveness — which Nussbaum defines as “a change of heart on the part of the victim, who gives up anger and resentment in response to the offender’s confession and contrition†— is also warped into a transactional proposition wherein the wrongdoer must earn, through confession and apology, the wronged person’s morally superior grace.

Nussbaum outlines the core characteristics and paradoxes of anger:

Anger is an unusually complex emotion, since it involves both pain and pleasure [because] the prospect of retribution is pleasant… Anger also involves a double reference—to a person or people and to an act… The

focus of anger is an act imputed to the target, which is taken to be a wrongful damage.

Injuries may be the focus in grief as well. But whereas grief focuses on the loss or damage itself, and lacks a target (unless it is the lost person, as in “I am grieving for so-and-soâ€), anger starts with the act that inflicted the damage, seeing it as intentionally inflicted by the target — and then, as a result, one becomes angry, and one’s anger is aimed at the target. Anger, then, requires causal thinking, and some grasp of right and wrong.

[…]

Notoriously, however, people sometimes get angry when they are frustrated by inanimate objects, which presumably cannot act wrongfully… In 1988, the Journal of the American Medical Association published an article on “vending machine rageâ€: fifteen injuries, three of them fatal, as a result of angry men kicking or rocking machines that had taken their money without dispensing the drink. (The fatal injuries were caused by machines falling over on the men and crushing them.)

Beneath this tragicomic response lies a combination of personal insecurity, vulnerability, and what Nussbaum calls status-injury (or what Aristotle called down-ranking) — the perception that the wrongdoer has lowered the social status of the wronged — conspiring to produce a state of exasperating helplessness. Anger, Nussbaum argues, is how we seek to create an illusion of control where we feel none.

She writes:

Anger is not always, but very often, about status-injury. And status-injury has a narcissistic flavor: rather than focusing on the wrongfulness of the act as such, a focus that might lead to concern for wrongful acts of the same type more generally, the status-angry person focuses obsessively on herself and her standing vis-Ã -vis others.

[…]

We are prone to anger to the extent that we feel insecure or lacking control with respect to the aspect of our goals that has been assailed — and to the extent that we expect or desire control. Anger aims at restoring lost control and often achieves at least an illusion of it. To the extent that a culture encourages people to feel vulnerable to affront and down-ranking in a wide variety of situations, it encourages the roots of status-focused anger.

Nowhere is anger more acute, nor more damaging, than in intimate relationships, where the stakes are impossibly high. Because they are so central to our flourishing and because our personal investment in them is at its deepest, the potential for betrayal there is enormous and therefore enormously vulnerable-making. Crucially, Nussbaum argues, intimate relationships involve

trust, which is predicated on inevitable vulnerability. She considers what trust actually means:

Trust … is different from mere reliance. One may rely on an alarm clock, and to that extent be disappointed if it fails to do its job, but one does not feel deeply vulnerable, or profoundly invaded by the failure. Similarly, one may rely on a dishonest colleague to continue lying and cheating, but this is reason, precisely, not to trust that person; instead, one will try to protect oneself from damage. Trust, by contrast, involves opening oneself to the possibility of betrayal, hence to a very deep form of harm. It means relaxing the self-protective strategies with which we usually go through life, attaching great importance to actions by the other over which one has little control. It means, then, living with a certain degree of helplessness.

Is trust a matter of belief or emotion? Both, in complexly related ways. Trusting someone, one believes that she will keep her commitments, and at the same time one appraises those commitments as very important for one’s own flourishing. But that latter appraisal is a key constituent part of a number of emotions, including hope, fear, and, if things go wrong, deep grief and loss. Trust is probably not identical to those emotions, but under normal circumstances of life it often proves sufficient for them. One also typically has other related emotions toward a person whom one trusts, such as love and concern. Although one typically does not decide to trust in a deliberate way, the willingness to be in someone else’s hands is a kind of choice, since one can certainly live without that type of dependency… Living with trust involves profound vulnerability and some helplessness, which may easily be deflected into anger.

In the collection’s standout essay, titled “Against Self-Criticism,†Phillips reaches across the space-time of culture to both revolt against and pay homage to Susan Sontag’s masterwork

Against Interpretation, and examines “our virulent, predatory self-criticism [has] become one of our greatest pleasures.†He writes:

In broaching the possibility of being, in some way, against self-criticism, we have to imagine a world in which celebration is less suspect than criticism; in which the alternatives of celebration and criticism are seen as a determined narrowing of the repertoire; and in which we praise whatever we can.

But we have become so indoctrinated in this conscience of self-criticism, both collectively and individually, that we’ve grown reflexively suspicious of that alternative possibility. (Kafka, the great patron-martyr of self-criticism, captured this pathology perfectly:

“There’s only one thing certain. That is one’s own inadequacy.â€) Phillips writes:

Self-criticism, and the self as critical, are essential to our sense, our picture, of our so-called selves.

[…]

Nothing makes us more critical, more confounded — more suspicious, or appalled, or even mildly amused — than the suggestion that we should drop all this relentless criticism; that we should be less impressed by it. Or at least that self-criticism should cease to have the hold over us that it does.

“Nothing awakens us to the reality of life so much as a true love,â€

“Nothing awakens us to the reality of life so much as a true love,†Vincent van Gogh

wrote to his brother.

“Why is love rich beyond all other possible human experiences and a sweet burden to those seized in its grasp?†philosopher Martin Heidegger asked in his

electrifying love letters to Hannah Arendt.

“Because we become what we love and yet remain ourselves.†Still, nearly every anguishing aspect of love arises from the inescapable tension between this longing for transformative awakening and the sleepwalking selfhood of our habitual patterns. True as it may be that

frustration is a prerequisite for satisfaction in romance, how are we to reconcile the sundering frustration of these polar pulls?

The multiple sharp-edged facets of this question are what

Alain de Botton explores in

The Course of Love (

public library) — a meditation on the beautiful, tragic tendernesses and fragilities of the human heart, at once unnerving and assuring in its psychological insightfulness. At its heart is a lamentation of — or, perhaps, an admonition against — how the classic Romantic model has sold us on a number of self-defeating beliefs about the most essential and nuanced experiences of human life: love, infatuation, marriage, sex, children, infidelity, trust.

Alain de Botton

A sequel of sorts to his 1993 novel

On Love, the book is bold bending of form that fuses fiction and De Botton’s

supreme forte, the essay — twined with the narrative thread of the romance between the two protagonists are astute observations at the meeting point of psychology and philosophy, spinning out from the particular problems of the couple to unravel broader insight into the universal complexities of the human heart.

In fact, as the book progresses, one gets the distinct and surprisingly pleasurable sense that De Botton has sculpted the love story around the robust armature of these philosophical meditations; that the essay is the raison d’être for the fiction.

In one of these contemplative interstitials, De Botton writes:

Maturity begins with the capacity to sense and, in good time and without defensiveness, admit to our own craziness. If we are not regularly deeply embarrassed by who we are, the journey to self-knowledge hasn’t begun.

In 1885, a young woman sent the editor of her hometown newspaper a

brilliant response to a letter by a patronizing chauvinist, which the paper had published under the title “What Girls Are Good For.†The woman, known today as Nellie Bly, so impressed the editor that she was hired at the paper and went on to become a trailblazing journalist,

circumnavigating the globe in 75 days with only a duffle bag and risking her life to write

a seminal exposé of asylum abuse, which forever changed legal protections for the mentally ill. But Bly’s courage says as much about her triumphant character as it does about the tragedies of her culture — she is celebrated as a hero in large part because she defied and transcended the limiting gender norms of the Victorian era, which reserved courageous and adventurous feats for men, while raising women to be diffident, perfect, and perfectly pretty instead.

Writer

Caroline Paul, one of the first women on San Francisco’s firefighting force and an experimental plane pilot,

believes that not much has changed in the century since — that beneath the surface progress, our culture still nurses girls on “the insidious language of fear†and boys on that of bravery and resilience. She offers an intelligent and imaginative antidote in

The Gutsy Girl: Escapades for Your Life of Epic Adventure (

public library) — part memoir, part manifesto, part aspirational workbook, aimed at tween girls but speaking to the ageless, ungendered spirit of adventure in all of us, exploring what it means to be brave, to persevere, to break the tyranny of perfection, and to laugh at oneself while setting out to do the seemingly impossible.

Illustrated by Paul’s partner (and my

frequent collaborator), artist and graphic journalist

Wendy MacNaughton, the book features sidebar celebrations of diverse “girl heroes†of nearly every imaginable background, ranging from famous pioneers like Nellie Bly and astronaut Mae Jemison to little-known adventurers like canopy-climbing botanist Marie Antoine, prodigy rock-climber Ashima Shiraishi, and barnstorming pilot and parachutist Bessie “Queen Bess†Coleman.

A masterful

memoirist who has previously written about

what a lost cat taught her about finding human love and

what it’s like to be a twin, Paul structures each chapter as a thrilling micro-memoir of a particular adventure from her own life — building a milk carton pirate ship as a teenager and sinking it triumphantly into the rapids, mastering a challenging type of paragliding as a young woman, climbing and nearly dying on the formidable mount Denali as an adult.

Let me make one thing clear: Throughout the book, Paul does a remarkably thoughtful job of pointing out the line between adventurousness and recklessness. Her brushes with disaster, rather than lionizing heedlessness, are the book’s greatest gift precisely because they decondition the notion that an adventure is the same thing as an achievement — that one must be perfect and error-proof in every way in order to live a daring and courageous life. Instead, by chronicling her many missteps along the running starts of her leaps, she assures the young reader over and over that owning up to mistakes isn’t an attrition of one’s courage but an essential building block of it. After all, the fear of humiliation is perhaps what undergirds all fear, and in our culture of

stubborn self-righteousness, there are few things we resist more staunchly, to the detriment of our own growth, than looking foolish for being wrong. The courageous, Paul reminds us, trip and fall, often in public, but get right back up and leap again.

Indeed, the book is a lived and living testament to psychologist Carol Dweck’s

seminal work on the “fixed†vs. “growth†mindsets — life-tested evidence that courage is the fruit not of perfection but of doggedness in the face of fallibility, fertilized by the choice (and it is a choice, Paul reminds us over and over) to get up and dust yourself off each time.

But Paul wasn’t always an adventurer. She reflects:

I had been a shy and fearful kid. Many things had scared me. Bigger kids. Second grade. The elderly woman across the street. Being called on in class. The book

Where the Wild Things Are. Woods at dusk. The way the bones in my hand crisscrossed.

Being scared was a terrible feeling, like sinking in quicksand. My stomach would drop, my feet would feel heavy, my head would prickle. Fear was an all-body experience. For a shy kid like me it was overwhelming.

Let me pause here to note that Caroline Paul is one of the most extraordinary human beings I know — a modern-day Amazon, Shackleton, Amelia Earhart, and Hedy Lamarr rolled into one — and since she is also a brilliant writer, the self-deprecating humor permeating the book serves a deliberate purpose: to assure us that no one is born a modern-day Amazon, Shackleton, Amelia Earhart, and Hedy Lamarr rolled into one, but the determined can become it by taking on challenges, conceding the possibility of imperfection and embarrassment, and seeing those outcomes as part of the adventure rather than as failure at achievement.

That’s exactly what Paul does in the adventures she chronicles. It’s time, after all, to replace that woeful

Victorian map of woman’s heart with a modern map of the gutsy girl spirit.

“No woman should say, ‘I am but a woman!’ But a woman! What more can you ask to be?â€

“No woman should say, ‘I am but a woman!’ But a woman! What more can you ask to be?†astronomer Maria Mitchell, who

paved the way for women in American science, admonished the first class of female astronomers at Vassar in 1876. By the middle of the next century, a team of unheralded women scientists and engineers were

powering space exploration at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Meanwhile, across the continent and in what was practically another country, a parallel but very different revolution was taking place: In the segregated South, a growing number of black female mathematicians, scientists, and engineers were steering early space exploration and helping American win the Cold War at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

Long before the term “computer†came to signify the machine that dictates our lives, these remarkable women were working as human “computers†— highly skilled professional reckoners, who thought mathematically and computationally for their living and for their country. When Neil Armstrong set his foot on the moon, his “giant leap for mankind†had been powered by womankind, particularly by Katherine Johnson — the “computer†who calculated Apollo 11’s launch windows and who was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama at age 97 in 2015, three years after the accolade was conferred upon John Glenn, the astronaut whose flight trajectory Johnson had made possible.

Katherine Johnson at her Langley desk with a globe, or “Celestial Training Device,†1960 (Photographs: NASA)

She writes:

Just as islands — isolated places with unique, rich biodiversity — have relevance for the ecosystems everywhere, so does studying seemingly isolated or overlooked people and events from the past turn up unexpected connections and insights to modern life.

Against a sobering cultural backdrop, Shetterly captures the enormous cognitive dissonance the very notion of these black female mathematicians evokes:

Before a computer became an inanimate object, and before Mission Control landed in Houston; before Sputnik changed the course of history, and before the NACA became NASA; before the Supreme Court case

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka established that separate was in fact not equal, and before the poetry of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream†speech rang out over the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Langley’s West Computers were helping America dominate aeronautics, space research, and computer technology, carving out a place for themselves as female mathematicians who were also black, black mathematicians who were also female.

Shetterly herself grew up in Hampton, which dubbed itself “Spacetown USA,†amid this archipelago of women who were her neighbors and teachers. Her father, who had built his first rocket in his early teens after seeing the Sputnik launch, was one of Langley’s African American scientists in an era when words we now shudder to hear were used instead of “African American.†Like him, the first five black women who joined Langley’s research staff in 1943 entered a segregated NASA — even though, as Shetterly points out, the space agency was among the most inclusive workplaces in the country, with more than fourfold the percentage of black scientists and engineers than the national average.

Over the next forty years, the number of these trailblazing black women mushroomed to more than fifty, revealing the mycelia of a significant groundswell. Shetterly’s favorite Sunday school teacher had been one of the early computers — a retired NASA mathematician named Kathleen Land. And so Shetterly, who considers herself “as much a product of NASA as the Moon landing,†grew up believing that black women simply belonged in science and space exploration as a matter of course — after all, they populated her father’s workplace and her town, a town whose church “abounded with mathematicians.â€

Building 1236, my father’s daily destination, contained a byzantine complex of government-gray cubicles, perfumed with the grown-up smells of coffee and stale cigarette smoke. His engineering colleagues with their rumpled style and distracted manner seemed like exotic birds in a sanctuary. They gave us kids stacks of discarded 11×14 continuous-form computer paper, printed on one side with cryptic arrays of numbers, the blank side a canvas for crayon masterpieces. Women occupied many of the cubicles; they answered phones and sat in front of typewriters, but they also made hieroglyphic marks on transparent slides and conferred with my father and other men in the office on the stacks of documents that littered their desks. That so many of them were African American, many of them my grandmother’s age, struck me as simply a part of the natural order of things: growing up in Hampton, the face of science was brown like mine.

[…]

The community certainly included black English professors, like my mother, as well as black doctors and dentists, black mechanics, janitors, and contractors, black cobblers, wedding planners, real estate agents, and undertakers, several black lawyers, and a handful of black Mary Kay salespeople. As a child, however, I knew so many African Americans working in science, math, and engineering that I thought that’s just what black folks did.

Katherine Johnson, age 98 (Photograph: Annie Leibovitz for

Vanity Fair)

“Words are events, they do things, change things,â€

“Words are events, they do things, change things,†Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in her beautiful meditation on

the power and magic of real human conversation.

“They transform both speaker and hearer; they feed energy back and forth and amplify it. They feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it.†Hardly anyone in our time has been a greater amplifier of spirits than longtime journalist,

On Being host, and patron saint of nuance

Krista Tippett — a modern-day

Simone Weil who has been fusing spiritual life and secular culture with remarkable virtuosity through her conversations with physicists and poets, neuroscientists and novelists, biologists and Benedictine monks, united by the quality of heart and mind that Einstein so beautifully termed “spiritual genius.â€

In her interviews with the great spiritual geniuses of our time, Tippett has cultivated a rare space for reflection and redemption amid our reactionary culture — a space framed by her generous questions exploring the life of meaning. In

Becoming Wise: An Inquiry into the Mystery and Art of Living (

public library), Tippett distills more than a decade of these conversations across disciplines and denominations into a wellspring of wisdom on the most elemental questions of being human — questions about happiness, morality, justice, wellbeing, and love — reanimated with a fresh vitality of insight.

Krista Tippett

At the core of Tippett’s inquiry is the notion virtue — not in the limiting, prescriptive sense with which scripture has imbued it, but in the expansive, empowering sense of a psychological, emotional, and spiritual technology that allows us to first fully inhabit, then conscientiously close the gap between who we are and who we aspire to be.

She explores five primary fertilizers of virtue: words — the language we use to tell the stories we tell about who we are and how the world works; flesh — the body as the birthplace of every virtue, rooted in the idea that “how we inhabit our senses tests the mettle of our soulsâ€; love — a word so overused that it has been emptied of meaning yet one that gives meaning to our existence, both in our most private selves and in the fabric of public life; faith — Tippett left a successful career as a political journalist in divided Berlin in the 1980s to study theology not in order to be ordained but in order to question power structures and examine the grounds of moral imagination through the spiritual wisdom of the ages; and hope — an orientation of the mind and spirit predicated not on the blinders of optimism but on a lucid lens on the possible furnished by an active, unflinching reach for it.

If I’ve learned nothing else, I’ve learned this: a question is a powerful thing, a mighty use of words. Questions elicit answers in their likeness. Answers mirror the questions they rise, or fall, to meet. So while a simple question can be precisely what’s needed to drive to the heart of the matter, it’s hard to meet a

simplistic question with anything but a simplistic answer. It’s hard to transcend a combative question. But it’s hard to resist a generous question. We all have it in us to formulate questions that invite honesty, dignity, and revelation. There is something redemptive and life-giving about asking better questions.

For decades,

Annie Dillardhas beguiled those in search of truth and beauty in the written word with the lyrical splendor and wakeful sagacity of her prose.

The Abundance: Narrative Essays Old and New(

public library) collects her finest work, spanning such varied subjects as writing, the consecrating art of attention, and the surreal exhilaration of witnessing a total solar eclipse.

In a beautiful 1989 piece titled “A Writer in the World,†Dillard writes:

People love pretty much the same things best. A writer, though, looking for subjects asks not after what he loves best, but what he alone loves at all… Why do you never find anything written about that idiosyncratic thought you advert to, about your fascination with something no one else understands? Because it is up to you. There is something you find interesting, for a reason hard to explain because you have never read it on any page; there you begin. You were made and set here to give voice to this, your own astonishment.

And yet this singular voice is refined not by the stubborn flight from all that has been said before but by a deliberate immersion in the very best of it. Like Hemingway, who insisted that aspiring writers should metabolize a

certain set of essential books, Dillard counsels:

The writer studies literature, not the world. He lives in the world; he cannot miss it. If he has ever bought a hamburger, or taken a commercial airplane flight, he spares his readers a report of his experience. He is careful of what he reads, for that is what he will write. He is careful of what he learns, because that is what he will know.

The writer as a consequence reads outside his time and place.

The most significant animating force of great art, Dillard argues, is the artist’s willingness to hold nothing back and to create, always, with an unflappable generosity of spirit:

One of the few things I know about writing is this: Spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Don’t hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The very impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful; it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.

All life is lived in the shadow of its own finitude, of which we are always aware — an awareness we systematically blunt through the daily distraction of living. But when this finitude is made acutely imminent, one suddenly collides with awareness so acute that it leaves no choice but to fill the shadow with as much light as a human being can generate — the sort of inner illumination we call meaning: the meaning of life.

That tumultuous turning point is what neurosurgeon

Paul Kalanithi chronicles in

When Breath Becomes Air(

public library), also among the year’s

best science books — his piercing memoir of being diagnosed with terminal cancer at the peak of a career bursting with potential and a life exploding with aliveness. Partway between

Montaigne and

Oliver Sacks, Kalanithi weaves together philosophical reflections on his personal journey with stories of his patients to illuminate the only thing we have in common — our mortality — and how it spurs all of us, in ways both minute and monumental, to pursue a life of meaning.

What emerges is an uncommonly insightful, sincere, and sobering revelation of how much our sense of self is tied up with our sense of potential and possibility — the selves we would like to become, those we work tirelessly toward becoming. Who are we, then, and what remains of “us†when that possibility is suddenly snipped?

Paul Kalanithi in 2014 (Photograph: Norbert von der Groeben/Stanford Hospital and Clinics)

At age thirty-six, I had reached the mountaintop; I could see the Promised Land, from Gilead to Jericho to the Mediterranean Sea. I could see a nice catamaran on that sea that Lucy, our hypothetical children, and I would take out on weekends. I could see the tension in my back unwinding as my work schedule eased and life became more manageable. I could see myself finally becoming the husband I’d promised to be.

And then the unthinkable happens. He recounts one of the first incidents in which his former identity and his future fate collided with jarring violence:

My back stiffened terribly during the flight, and by the time I made it to Grand Central to catch a train to my friends’ place upstate, my body was rippling with pain. Over the past few months, I’d had back spasms of varying ferocity, from simple ignorable pain, to pain that made me forsake speech to grind my teeth, to pain so severe I curled up on the floor, screaming. This pain was toward the more severe end of the spectrum. I lay down on a hard bench in the waiting area, feeling my back muscles contort, breathing to control the pain — the ibuprofen wasn’t touching this — and naming each muscle as it spasmed to stave off tears: erector spinae, rhomboid, latissimus, piriformis…

A security guard approached. “Sir, you can’t lie down here.â€

“I’m sorry,†I said, gasping out the words. “Bad … back … spasms.â€

“You still can’t lie down here.â€

[…]

I pulled myself up and hobbled to the platform.

Like the book itself, the anecdote speaks to something larger and far more powerful than the particular story — in this case, our cultural attitude toward what we consider the failings of our bodies: pain and, in the ultimate extreme, death. We try to dictate the terms on which these perceived failings may occur; to make them conform to wished-for realities; to subvert them by will and witless denial. All this we do because, at bottom, we deem them impermissible — in ourselves and in each other.

This “discovering faculty†of the imagination, which breathes life into both the most captivating myths and the deepest layers of reality, is what animated Italian artist Alessandro Sanna one winter afternoon when he glimpsed a most unusual tree branch from the window of a moving train — a branch that looked like a sensitive human silhouette, mid-fall or mid-embrace.

As Sanna cradled the enchanting image in his mind and began sketching it, he realized that something about the “body language†of the branch reminded him of a small, delicate, terminally ill child he’d gotten to know during his visits to Turin’s Pediatric Hospital. In beholding this common ground of tender fragility, Sanna’s imagination leapt to a foundational myth of his nation’s storytelling — the Pinocchio story.

In the astonishingly beautiful and tenderhearted

Pinocchio: The Origin Story (

public library), also among the year’s

loveliest picture-books, Sanna imagines an alternative prequel to the beloved story, a wordless genesis myth of the wood that became Pinocchio, radiating a larger cosmogony of life, death, and the transcendent continuity between the two.

A fitting follow-up to

The River — Sanna’s exquisite visual memoir of life on the Po River in Northern Italy, reflecting on the seasonality of human existence — this imaginative masterwork dances with the cosmic unknowns that eclipse human life and the human mind with their enormity: questions like what life is, how it began, and what happens when it ends.

Origin myths have been our oldest sensemaking mechanism for wresting meaning out of these as-yet-unanswered, perhaps

unanswerable questions. But rather than an argument with science and our secular sensibility, Sanna’s lyrical celebration of myth embodies Margaret Mead’s insistence on

the importance of poetic truth in the age of facts.

It is both a pity and a strange comfort that Sanna’s luminous, buoyant watercolors and his masterful subtlety of scale don’t fully translate onto this screen — his analog and deeply humane art is of a different order, almost of a different time, and yet woven of the timeless and the eternal.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered