Big Data Could Help Some of the 200,000 NYC Households That Get Eviction Notices This Year

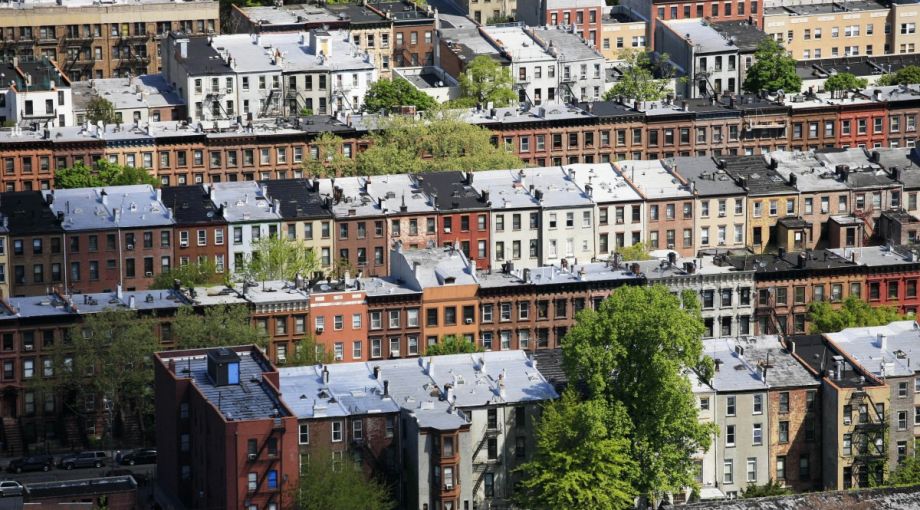

An eviction assistance pilot program using data analytics helped about 65 families avoid homelessness last year in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

Every renter’s bad dream is to get evicted, but that happens for 200,000 households a year in New York City. Not all evictions, however, are equal in terms of the devastation they cause. A college student who has blown his rent money on beer, for example, is much less likely to end up in a homeless shelter than a single mother struggling to get by.

The problem for social service agencies is figuring out who’s at risk of imminently becoming homeless amid thousands of eviction notices, and reaching those who need help. The nonprofit data analytics firm SumAll is trying to help with that challenge.

Taking a page from the playbook of marketing firms who use “big data” to target potential customers, SumAll has developed a tool that uses data — court records, shelter history, demographic information — to identify people at risk of becoming homeless. SumAll’s algorithm helps social workers decide where to focus their efforts — down to the individual.

“Think about a highly targeted marketing campaign trying to sell something,” explains Stefan Heeke, SumAll’s CEO. “This is the same thing.”

Last summer, SumAll conducted its first pilot in collaboration with CAMBA, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit social service organization. They tracked four districts and targeted outreach in one, the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood.

Pre-SumAll, CAMBA’s efforts to reach out to families going through the protracted eviction process was arduous. Social workers would look through the entire list of new eviction cases at Brooklyn’s Kings County Housing Court — roughly 5,000 per month — and then manually figure out which addresses fell in the areas they serve, says Melissa Mowery, vice president of CAMBA’s eviction counseling project, HomeBase. They then would mail letters to those in their zones, about 400 a month telling people about their eviction prevention counseling services.

With the help of SumAll, they were able to first geo-code the list and figure out which addresses were in the right neighborhoods — a process that took hours rather than days. “Hello, that saved a lot of manpower,” Mowery says. Then they used SumAll’s tool to figure out the 30 to 50 most at-risk cases. “At-risk” indicators included previous experience with the shelter system (using data from the city’s Department of Homeless Services), education level, employment status, age and even factors going back to childhood such as interaction with the foster care system. (All of this is public information.)

During the pilot, at-risk families received several letters in the mail — more personalized than previous outreach letters — and they were given a hotline number to call or text to set up an appointment. Only targeted families were given the hotline number, so their calls went to the top of the priority list, making the process of connecting them with services as efficient as possible.

The pilot results were promising. With SumAll’s data analysis, CAMBA was able to connect 50 percent more families in the test neighborhood with eviction prevention services compared to demographically similar neighborhoods nearby over the same period of time. That’s about 65 families that avoided ending up in a shelter. “That was huge, really huge,” says Mowery.

The use of big data to target individuals has a shaky reputation. “You don’t want big data to be used in ways that would invade privacy or would be used in ways that could have negative repercussions in other contexts,” says Jay Stanley, senior policy analyst with the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy and Technology Project. But, he says, “Incentives matter. The incentives here are for the social service agency to provide services to those in need the most, which is different from other contexts where the interests of the entity doing the data mining may run counter to the subjects of the data mining.” He warns that the analysis must be sound, or it could potentially exclude some in need of services.

“It’s kind of controversial, targeting in the social service world,” Mowery admits.

She says part of the controversy comes from the idea that social service agencies should cast a wide net, to everyone who might be in need. But this approach of trawling for any and all possible clients, she says, wastes time and resources — both of which are thin at CAMBA, as with most nonprofits.

With SumAll’s tool, her team got the most at-risk families through the door. “Bam, these are the 50 people you need to be thinking about,” she says. “Don’t worry about these other 4,550.”

Several nonprofits in New York are interested in using the tool. The system requires access to a robust database from government and the courts, Heeke says. One challenge is in accessing eviction filings, which lie in the hands of the city and housing courts. Currently SumAll is re-negotiating relationships with officials in the new administration to streamline access to data. But with the right cooperation, Heeke says, “targeting critical services to most vulnerable populations could be done in any neighborhood, in any city.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Maura Ewing is a Brooklyn-based writer. She writes (mostly) about affordable housing and criminal justice. You can read more of her work here.

And the Oscar Goes to … a City?

(Photo by European People’s Party)

From platinum-certified bike cities to LEED buildings and points-earning waterfronts, green infrastructure advocates are increasingly going the way of second-grade teachers and handing out gold stars. With at least two new certification programs launching this month, I spoke with several groups about why they’re turning to awards instead of simply lobbying for code and policy change.

Roland Lewis, CEO of Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance, says his organization’s new certification program, dubbed WEDG for Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines, relies on a principal “appealing to human nature”: competition.

Launched last week, the WEDG program, billed as a “LEED for the waterfront,” is essentially a ratings system. Waterfront projects, from ports to shiny new esplanades, earn points if they’re prepared for sea-level rise, situated near ferry service or clean up an existing brownfield. (Those three examples come from the residential/commercial section; parks and industrial/maritime works have their own set of credits.)

Lewis says that MWA’s goal is to assemble a best-practice metric for public agencies and developers, especially as they reclaim more waterfronts nationwide. But in order to reach the many stakeholders involved in, say, a port-to-park project, Lewis believes that packaging matters.

“We could put it out as a booklet of suggestions that would hopefully be a bestseller, but that’s not too likely,” he says, when asked why MWA chose the certification route. The organization could also lobby policymakers for better environmental regulations — but many rules and codes already exist. The WEDG format, however, “turns the conversation around” from compliance to motivation.

MWA isn’t alone. The League of American Bicyclists employs a similar carrot-and-not-stick methodology through its Bicycle Friendly America program. A yearly assessment of businesses, communities and universities, the program ranks participants on a scale of bronze to diamond, evaluating everything from enforcement practices to lanes.

With its Olympics-style ratings, the program’s achievement-oriented strategy isn’t exactly subtle — but like trophies, medals and gold stars, it seems to work.

“I don’t really believe that [policymakers and communities] are making decisions based on an award system. They share a desire for the outcomes we advocate,” says Bill Nesper, the League’s vice president of programs. “But if you set up strong targets, people want to hit them.”

As one of the nation’s most visible bike lobbying organizations — “from the halls of Congress to the streets of your community,” a tagline on its website reads — the League is no stranger to traditional advocacy. But since launching the program in 2002, Nesper says the League has watched participant demographics change from urban to suburban and even rural. Small communities whose names wouldn’t even be recognized on Capitol Hill made systemic changes to accommodate bikers based on the program.

“Communities like the recognition,” he adds.

A third certification, being unveiled by Bay Area organization TransForm today, takes straight-A achievement to an entirely new level. (Disclosure: TransForm is funded by some of the same sources as Next City.)

Already, its GreenTRIP certification program ranks multi-family housing with an unusual goal — reducing free and subsidized parking. Apartment and condo providers can become GreenTRIP-certified through a number of strategies, which have traditionally included unbundling the price of parking from rent (i.e., ditch your car, pay less), discounting transit passes and providing free car-share memberships. TransForm’s new platinum-level certification is a step up, based on one development that was able to scrap its $2.3 million garage entirely.

According to Ann Cheng, GreenTRIP program developer, the certification acts like a political endorsement.

“It helps to have that third-party validation and approval,” she says. “People have really busy lives. They need a quick gauge of who’s lining up on controversial projects.”

GreenTRIP programs are more numbers-oriented than a traditional endorsement, Cheng says, but like the bike and waterfront awards, they’re essentially motivators. Because TransForm is a third party and not a government organization, the company’s job isn’t to mandate code adoption or environmental regulation compliance.

“Like any A student, our developers want to go above and beyond,” she says. “They’re not being forced to do anything, but they want our certification.”

“TransForm also does ‘traditional advocacy,’ by speaking at meetings [and] starting mass sign-on letters/emails,” she adds later in an email. “But this type of ‘stick’-based advocacy only gets you so far in long, drawn-out project-specific battles.”

Echoing Lewis, she adds that, in many cases, human nature just seems to be more responsive to the carrot.

The Works is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Rachel Dovey is an award-winning freelance writer and former USC Annenberg fellow living at the northern tip of California’s Bay Area. She writes about infrastructure, water and climate change and has been published by Bust, Wired, Paste, SF Weekly, the East Bay Express and the North Bay Bohemian.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered