In 2016, I poured tremendous time, thought, love, and resources into Brain Pickings, which remains free. If you found any joy and stimulation here last year, please consider supporting my labor of love with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner:

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount:

And if you've already donated, from the bottom of my heart: THANK YOU.

|

|

Hello, Larry! If you missed last week's edition – Steinbeck's elevating perspective on how to start a new year, Neil Gaiman's animated tribute to Leonard Cohen, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this newsletter, please consider supporting my labor of love with a donation – in 2016, I spent thousands of hours and tremendous resources on it, and every little bit of support helps enormously. Hello, Larry! If you missed last week's edition – Steinbeck's elevating perspective on how to start a new year, Neil Gaiman's animated tribute to Leonard Cohen, and more – you can catch up right here. And if you're enjoying this newsletter, please consider supporting my labor of love with a donation – in 2016, I spent thousands of hours and tremendous resources on it, and every little bit of support helps enormously.

|

In case you missed them:

“If we design workplaces that permit people to find meaning in their work, we will be designing a human nature that values work,†“If we design workplaces that permit people to find meaning in their work, we will be designing a human nature that values work,â€psychologist Barry Schwartz wrote in his inquiry into what motivates us to work. But human nature itself is a moody beast. “Given the smallest excuse, one will not work at all,†John Steinbeck lamented in his diary of the creative process as he labored over the novel that would soon earn him the Pulitzer Prize and become the cornerstone for his Nobel Prize two decades later. Work, of course, has a profoundly different meaningfor the artist than it does for the person punching into and out of a nine-to-five workplace. And yet even those fortunate enough to be animated by a deep sense of purpose in a vocation that ensures their livelihood can succumb to the occasional — or even frequent — spell of paralysis at the prospect of another day of work. What, then, are we to do on such days when we simply can’t muster the motivation to get out of bed?

Aurelius writes:

At dawn, when you have trouble getting out of bed, tell yourself: “I have to go to work — as a human being. What do I have to complain of, if I’m going to do what I was born for — the things I was brought into the world to do? Or is thiswhat I was created for? To huddle under the blankets and stay warm?â€

To the mind’s natural protestation that staying under the blankets simply feels nicer, Aurelius retorts:

So you were born to feel “nice� Instead of doing things and experiencing them? Don’t you see the plants, the birds, the ants and spiders and bees going about their individual tasks, putting the world in order, as best they can? And you’re not willing to do your job as a human being? Why aren’t you running to do what your nature demands?

Our nature, he insists, is to live a life of service — to help others and contribute to the world. Any resistance to this inherent purpose is therefore a negation of our nature and a failure of self-love. He writes:

You don’t love yourself enough. Or you’d love your nature too, and what it demands of you.

Many centuries before psychologists identified the experience of “flow†in creative work, he considers a key characteristic of people who love what they do:

When they’re really possessed by what they do, they’d rather stop eating and sleeping than give up practicing their arts.

Is helping others less valuable to you? Not worth your effort?

He revisits the subject in another meditation:

When you have trouble getting out of bed in the morning, remember that your defining characteristic— what defines a human being — is to work with others. Even animals know how to sleep. And it’s the characteristic activity that’s the more natural one — more innate and more satisfying.

To be alive is to marvel — at least occasionally, at least with glimmers of some deep intuitive wonderment — at the Rube Goldberg machine of chance and choice that makes us who we are as we half-stride, half-stumble down the improbable paths that lead us back to ourselves. My own life was shaped by one largely impulsive choice at age thirteen, and most of us can identify points at which we could’ve pivoted into a wholly different direction — to move across the continent or build a home here, to leave the tempestuous lover or to stay, to wait for another promotion or quit the corporate day job and make art. Even the seemingly trivial choices can butterfly enormous ripples of which we may remain wholly unwitting — we’ll never know the exact misfortunes we’ve avoided by going down this street and not that, nor the exact magnitude of our unbidden graces.

Perhaps our most acute awareness of the lacuna between the one life we do have and all the lives we could have had comes in the grips of our fear of missing out — those sudden and disorienting illuminations in which we recognize that parallel possibilities exists alongside our present choices. “Our lived lives might become a protracted mourning for, or an endless tantrum about, the lives we were unable to live,†wrote the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips in his elegant case for the value of our unlived lives. “But the exemptions we suffer, whether forced or chosen, make us who we are.â€

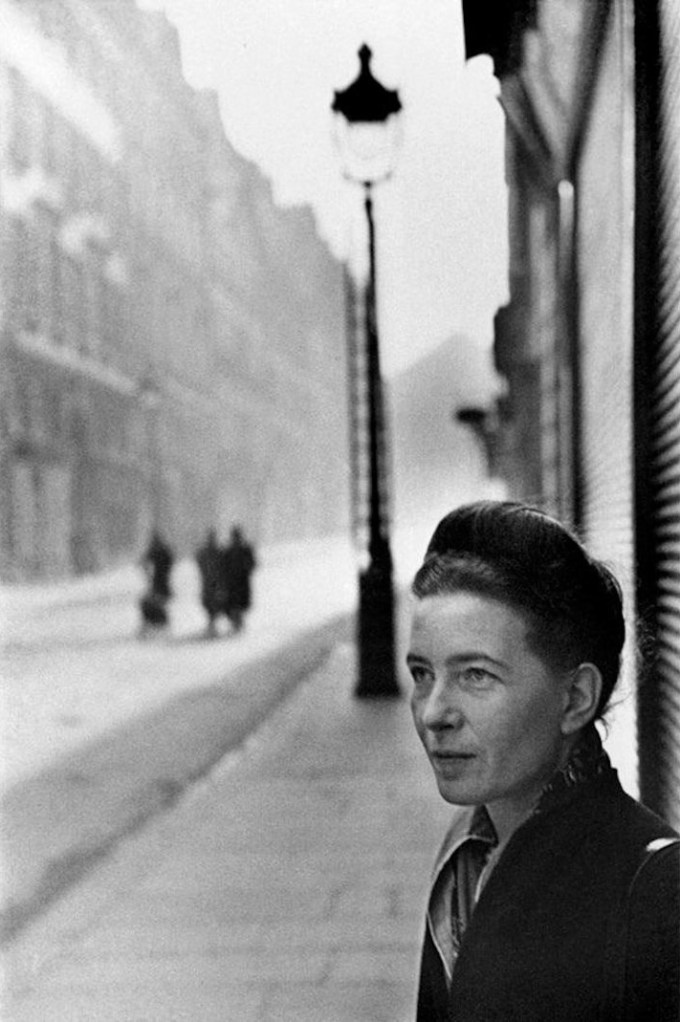

No one has captured that ultimate existential awareness more beautifully, nor with greater nuance, than the trailblazing French existentialist philosopher and feminist Simone de Beauvoir (January 9, 1908–April 14, 1986) in her autobiography, All Said and Done ( public library).

Simone de Beauvoir, 1946 (Photograph: Henri Cartier-Bresson)

From the fortunate rostrum of her own long life, De Beauvoir reflects on this constellation of chance and choice:

Every morning, even before I open my eyes, I know I am in my bedroom and my bed. But if I go to sleep after lunch in the room where I work, sometimes I wake up with a feeling of childish amazement — why am I myself? What astonishes me, just as it astonishes a child when he becomes aware of his own identity, is the fact of finding myself here, and at this moment, deep in this life and not in any other. What stroke of chance has brought this about? What astonishes me, just as it astonishes a child when he becomes aware of his own identity, is the fact of finding myself here, and at this moment, deep in this life and not in any other.

With an eye to the element of chance and its myriad manifestations, she adds:

The penetration of that particular ovum by that particular spermatozoon, with its implications of the meeting of my parents and before that of their birth and the births of all their forebears, had not one chance in hundreds of millions of coming about. And it was chance, a chance quite unpredictable in the present state of science, that caused me to be born a woman. From that point on, it seems to me that a thousand different futures might have stemmed from every single movement of my past: I might have fallen ill and broken off my studies; I might not have met Sartre; anything at all might have happened.

But the most curious part of this perplexity, De Beauvoir notes, is that despite the larger cosmic accident of all lifeand the chance nature of our particular lives within it, we experience ourselves and our existence as non-accidental — a disconnect that fringes on the free will paradox. She writes:

Tossed into the world, I have been subjected to its laws and its contingencies, ruled by wills other than my own, by circumstance and by history: it is therefore reasonable for me to feel that I am myself contingent. What staggers me is that at the same time I am not contingent. If I had not been born no question would have arisen: I have to take the fact that I do exist as my starting point. To be sure, the future of the woman I have been may turn me into someone other than myself. But in that case it would be this other woman who would be asking herself who she was. For the person who says “Here am I†there is no other coexisting possibility. Yet this necessary coincidence of the subject and his history is not enough to do away with my perplexity. My life: it is both intimately known and remote; it defines me and yet I stand outside it.

Like Einstein’s universe, it is both boundless and finite. Boundless: it runs back through time and space to the very beginnings of the world and to its utmost limits. In my being I sum up the earthly inheritance and the state of the world at this moment.

[…]

And yet life is also a finite reality. It possesses an inner heart, a centre of interiorization, a me which asserts that it is always the same throughout the whole course. A life is set within a given space of time; it has a beginning and an end; it evolves in given places, always retaining the same roots and spinning itself an unchangeable past whose opening toward the future is limited. It is possible to grasp and define a life as one can grasp and define a thing, since a life is “an unsummed whole,†as Sartre puts it, a detotalized totality, and therefore it has no being. But one can ask certain questions about it.

Of course, as De Beauvoir’s American peer and contemporary Susanne Langer has memorably pointed out, our questions invariably shape our answers. But to this central question of whether and to what degree we are contingent upon chance, De Beauvoir offers an answer that radiates the ultimate antidote to regret:

Chance … has a distinct meaning for me. I do not know where I might have been led by the paths that, as I look back, I think I might have taken but that in fact I did not take. What is certain is that I am satisfied with my fate and that I should not want it changed in any way at all. So I look upon these factors that helped me to fulfill it as so many fortunate strokes of chance.

Simone de Beauvoir, 1952 (Photograph: Gisèle Freund)

In his insightful reflection on the crucial difference between talent and genius, Schopenhauer likened talent to a marksman who hits a target others cannot hit, and genius to a marksman who hits a target others cannot see. Among humanity’s rare genius-seers was pioneering astrophysicist Vera Rubin(July 23, 1928–December 25, 2016) — a coruscating intellect animated by a sinewy tenacity, who overcame towering cultural odds by the sheer force of her unbridled curiosity and rigorous devotion to science. In confirming the existence of dark matter, Rubin revolutionized our understanding of the universe, paved the way for modern women in science, and recalibrated the stilted norms of her profession.

Rubin fell in love with the night sky as a young girl, but knew no astronomer, living or dead, to hold as a role model. Eventually, she came upon a children’s book about 19th-century trailblazer Maria Mitchell — America’s first professional female astronomer and the first woman admitted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences — whose story reframed Rubin’s landscape of possibility and emboldened her to pursue stargazing as a vocation rather than a hobby. “It never occurred to me that I couldn’t be an astronomer,†she told Alan Lightman many years later in their wonderful 1990 conversation.

Vera Rubin as an undergraduate at Vassar, 1940s

Rubin received a scholarship to Vassar, where Maria Mitchell had taught the first class of women astronomers as the first woman on the faculty nearly a century earlier. “As long as you stay away from science, you should do okay,†her chauvinist high school physics teacher counseled her upon receiving the admission news. Mercifully, she didn’t heed the unsubtle message — driven by the same tenacious obsessiveness that underlined her groundbreaking discoveries, she plunged straight into science and graduated from Vassar in 1948 as the only astronomy major in her class. Rejected from Princeton’s graduate program, which only admitted men, Rubin instead obtained her master’s degree from Cornell and Georgetown while nursing one child and pregnant with her second. (She would go on to raise four children, all of whom would become scientists.)

In her work on spectroscopy, Rubin drew on the revolutionary discoveries of the Harvard computers — the unheralded team of 19th-century women astronomers who classified stellar spectra decades before women were able to vote. In 1965, she broke a colossal glass ceiling by becoming the first woman to observe at the Palomar Observatory, home to the world’s most powerful telescopes at the time. She went on to do pioneering work on galaxy rotation, based on which she confirmed the existence of dark matter— a cornerstone of our modern understanding of the cosmos.

Vera Rubin with her “measuring engine†used to examine photographic plates, 1974

For decades, Rubin remained a tireless champion of science as a pillar of society. “We need senators who have studied physics and representatives who understand ecology,†she asserted in her electrifying 1996 Berkeley commencement address — a remark of chilling timeliness and urgency today.

That Rubin died without her Nobel Prize is nothing short of a travesty, bespeaking the flawed cultural machinery by which such honors are meted out. But there is higher-order consolation in the wise words of astrophysicist Janna Levin, whose own career was built on the path Rubin paved:

Scientists do not devote their lives to the sometimes lonely, agonizing, toilsome investigation of an austere universe because they want a prize.

In the preface to Bright Galaxies, Dark Matters ( public library) — Rubin’s anthology of essays, papers, and speeches spanning 36 years, her commencement address among them — she addresses one of the most central and most misunderstood principles of science: that the power of not-knowing is as essential to science as it is to art and that ignorance, rather than hindering knowledge, is the springboard for it. Rubin writes:

Scientists too seldom stress the enormity of our ignorance. Virtually everything we know about galaxies we have learned during the last 100 years… But what are the questions for future astronomers? What questions will astronomers be asking of the universe 100 years from now? A thousand years from now?

The questions easiest to enumerate, Rubin points out, are those identified but unanswered by the era — questions about the precise rate of expansion of the universe, the amount of mass it contains, the nature of dark matter, and the potential for life on other planets. But the more interesting questions, she suggests, are those “we barely know enough to ask†— among them, the possibility of other universes and the question of how the detection of gravitational waves, merely a hypothetical feat at the time of her writing, would change our understanding of the cosmos. (We’ve only just answered the latter, two decades later; as Rubin anticipated, the answer has profoundly altered our understanding of the universe.)

Echoing her formative role model — “The world of learning is so broad, and the human soul is so limited in power! We reach forth and strain every nerve, but we seize only a bit of the curtain that hides the infinite from us,â€Maria Mitchell had marveled in her diary more than a century earlier — Rubin writes:

As we peer into the universe we are peering into our past, but our “eyes†are weak and we have not yet seen to great distances. No one promised that we should live in the era that would unravel the mysteries of the cosmos. The edge of the universe is far beyond our grasp. Like Columbus, perhaps like the Vikings, we have peered into a new world and have seen that it is more mysterious and more complex than we had imagined. Still more mysteries of the universe remain hidden. Their discovery awaits the adventurous scientists of the future. I like it this way.

In early 2016, halfway through her eighty-seventh year, Rubin joined Twitter for approximately twenty-four hours, over the course of which she tweeted exactly six times: five aphoristic thoughts on human life and the universe, one piece of dark matter news, and one warm congratulatory note to a laureate of the Nobel Prize she herself was never awarded — a testament to her singleminded scientific devotion and her unbegrudging generosity of spirit.

To commemorate this irreplaceable woman, I’ve joined forces with artist Debbie Millman — who also helped me commemorate Oliver Sacks — on an original piece of art based on Rubin’s final Twitter aphorism: “Don’t shoot for the stars, we already know what’s there. Shoot for the space in between because that’s where the real mystery lies,†rendered in felt letters over the hand-painted abstract text of Rubin’s groundbreaking 1980 paper on galaxy rotation. The piece is available as an art print, canvas print, and stationery cards, with all proceeds benefiting the Association for Women in Science in Rubin’s name.

“There is, in sanest hours, a consciousness, a thought that rises, independent, lifted out from all else, calm, like the stars, shining eternal,†Walt Whitman wrote as he contemplated the experience of identity and the paradox of the self. And yet we know — we even feel — that what we experience as ourselves is not eternal but transient, an ever-changing constellation of components drawn from our living lives. This transient, emergent nature of personhood becomes acutely apparent and acutely disorienting as soon as we consider what makes one and one’s childhood self the “same†person despite a lifetime of biological, psychological, and spiritual change. But this transience itself is the wellspring of our vitality, the fountain at which we slake our thirst for life.

That paradoxical notion is what the great Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue (January 1, 1956–January 4, 2008) explores in a portion of Four Elements: Reflections on Nature ( public library) — a posthumous collection of previously unpublished papers, in which O’Donohue draws on his Celtic heritage, his poetic gift, and his lyrical approach to philosophy to explore how the corporeality and spirituality that mark our existence interact to reveal us to ourselves.

John O’Donohue (Photograph: Colm Hogan)

O’Donohue writes:

Selfhood is not an imperial possession of the human orphan. It is not exclusively human. Selfhood is more patient and ancient, a diverse intimacy of the earth with itself.

If the earth has the most ancient networks of selfhood, then the memory of the earth is the ultimate harvester and preserver of all happening and experience. In modern life, experience enjoys privileged status as the force which awakens, enables and stabilizes human growth. The significance of experience is intimately bound up with the urgency of modern individuality. This sense of individuality achieved its classical contour through the metaphysical scalpel of Descartes’ “Cogito†which cut the individual free from the cosmic webbing of scholasticism.

This concept of individuality was further intensified in German Idealism and Existentialism. Life is seen to be woven on the loom of individual experience.

Taking experience seriously must make it equally necessary to take the destiny or future of experience seriously. This is a particularly poignant necessity, given that the future of each experience is its disappearance. The destiny of every experience is transience.

Transience makes a ghost out of each experience. There was never a dawn that did not drop down into noon, never a noon which did not fade into evening, and never an evening that did not get buried in the graveyard of the night.

One remembers the sentence which won the contest of wisdom in ancient Greece: “This too will pass.†The pain of transience haunted Goethe’s Faust; he implored the beautiful figure who appeared to him: “Verweile doch, Du bist so schön!†Linger a while, for you are so beautiful!

O’Donohue considers the only human faculty that appeases and anneals us to the inescapable transience of all experience, including life itself:

Out of the fiber and density of each experience transience makes a ghost. The future, rich with possibility, becomes a vacant past. Every thing, no matter how painful, beautiful or sonorous, recedes into the silence of transience. Transience too is the maker of the final silence, the silence of death.

Is the silence which transience brings a vacant silence? Does everything vanish into emptiness? Like the patterns which birdflight makes in the air, is there nothing left? Where does the flame go when the candle is blown out? Is there a place where the past can gather? I believe there is. That place is memory. That which holds out against transience is memoria.

Memoria is always quietly at work, gathering and interweaving experience. Memoria is the place where our vanished lives secretly gather. For nothing that happens to us is ever finally lost or forgotten. In a strange way, everything that happens to us remains somehow still alive within us.

[…]

It is crucial to understand that experience itself is not merely an empirical process of appropriating or digesting blocks of life. Experience is rather a journey of transfiguration. Both that which is lived and the one who lives it are transfigured. Experience is not about the consumption of life, rather it is about the interflow of creation into the self and of the self into creation. This brings about subtle and consistently new configurations in both. That is the activity of growth and creativity.

Viewed against this perspective, the concealed nature of memoria is easier to understand. Memoria is the harvester and harvest of transfigured experience. Deep in the silent layers of selfhood, the coagulations of memoria are at work. It is because of this subtle integration of self and life that there is the possibility of any continuity in experience.

“All great truths are obvious truths,†Aldoux Huxley wrote, “but not all obvious truths are great truths.â€Perhaps it is an obvious truth, but it is also a great truth that years after his sudden and untimely death, O’Donohue lives on in our collective memoria through his transcendent writings, which continue to offer a consecrating lens on the transience we call life.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered