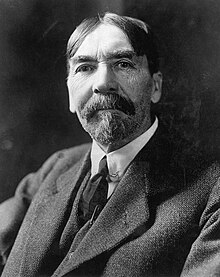

Thorstein Veblen

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Thorstein Bunde Veblen (1857–1929)

|

|

| Born | July 30, 1857 Cato, Wisconsin |

|---|---|

| Died | August 3, 1929 (aged 72) Sand Hill Road, Menlo Park, California |

| Nationality | Norwegian American |

| Field | Evolutionary economics; sociology |

| School/tradition | Institutional economics |

| Influences | Herbert Spencer,[1] William Graham Sumner, Karl Marx, Lester F. Ward, William James, William McDougall, Georges Vacher de Lapouge, John Dewey, Gustav von Schmoller, John Bates Clark, Henri de Saint-Simon,[2] Charles Fourier[3] |

| Influenced | Wesley Clair Mitchell, Clarence Edwin Ayres, John Kenneth Galbraith, C. Wright Mills, Robert A. Brady, Lewis Mumford, Harold Adams Innis, Edith Penrose, John M. Clark, Geoffrey Hodgson, Jonathan Nitzan, Shimshon Bichler |

| Contributions | Conspicuous consumption, penalty of taking the lead, ceremonial/instrumental dichotomy |

| Signature | |

Veblen is famous in the history of economic thought for combining a Darwinian evolutionary perspective with his new institutionalist approach to economic analysis. He combined sociology with economics in his masterpiece The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) where he argued that there was a fundamental split in society between those who make their way via exploit and those who make their way via industry. In early barbarian society this is the difference between the hunter and the gatherer in the tribe, but as society matures it is the difference between the landed gentry and the indentured servant. The titular manifestation of those with the power of exploit is the "leisure class" which is defined by its lack of productive economic activity and its commitment to demonstrations of idleness. As Veblen describes it, as societies mature, conspicuous leisure gives way to "conspicuous consumption", but both are performed for the sole purpose of making an invidious distinction based on pecuniary strength, the demonstration of wealth being the basis for social status.

Veblen was sympathetic to state ownership of industry, but he had a low opinion of workers[citation needed] and the labor movement and there is disagreement about the extent to which his views are compatible with Marxism,[4] socialism or anarchism. Veblen believed that technological developments would eventually lead to a socialist organization of economic affairs. The two were clearly different in that Veblen's views on socialism and the nature of the evolutionary process of economics differed sharply from that of Karl Marx. While Marx saw socialism as the final political precursor to communism, or the ultimate goal for civilization, and believed that the working class would be the group to establish it, Veblen saw socialism as one intermediate phase in an ongoing evolutionary process in society that would be brought about by the natural decay of the business enterprise system and by the inventiveness of engineers.

As a leading intellectual of the Progressive Era, he made sweeping attacks on production for profit, and his stress on the wasteful role of consumption for status greatly influenced socialist thinkers and engineers who sought a non-Marxist critique of capitalism.

Contents

Biography

Early life and family background

Veblen was born on July 30, 1857 in Cato, Wisconsin to Norwegian American immigrant parents, Thomas Veblen and Kari Bunde. He was the fourth of twelve children in the Veblen family. His parents emigrated from Norway to Milwaukee, Wisconsin on September 16, 1847, with little funds and no knowledge of English. Despite their limited circumstances as immigrants, Thomas Veblen’s knowledge in carpentry and construction paired with his wife’s supportive perseverance allowed them to establish a family farm, which is now a National Historic Landmark, in Nerstrand, Minnesota. The farmstead, and other similar settlements were referred to as little Norways, oriented by the religious and cultural traditions of the old country. The farmstead was also where Veblen spent most of his childhood.[5]Although Norwegian was his first language, he learned English from neighbors and at school, which he began at the age of five. In time, his parents learned to speak English fluently, however they continued to read predominantly Norwegian literature with and around their family on the farmstead. With time, the family farm grew more prosperous and allowed Veblen’s parents to provide their children with their primary hope of formal education. Unlike most immigrant families of the time, among Veblen’s siblings, all of them received training in lower schools and went on to receive higher education at the nearby Carleton College. Veblen’s sister, Emily, was recognized as the first woman to graduate from a Minnesota college. The eldest Veblen child, Andrew A. Veblen, ultimately became a professor of physics at Iowa State University and the father of one of America’s leading mathematicians, Dr. Oswald Veblen of Princeton University.[6]

Several critics have argued that Veblen's Norwegian background and his relative isolation from American society are essential to the understanding of his writings. David Riesman maintains that his background as a child of immigrants meant that he was alienated from his parents' previous culture, but that his living in a Norwegian society within America made him unable to completely "assimilate and accept the available forms of Americanism." [7] According to George M. Fredrickson the Norwegian society Veblen lived in was so isolated that when he left it "he was, in a sense, emigrating to America." [8]

Education

At seventeen, in 1874, Thorstein was sent to attend a nearby college named Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. Early in his schooling, he demonstrated both the bitterness and the sense of humor that would characterize his later works.[9]Veblen studied economics and philosophy under the guidance of the young John Bates Clark (1847–1938), who went on to become a leader in the new field of neoclassical economics. Clark’s influence on Veblen was great, and as Clark initiated him into the formal study of economics, Veblen came to recognize the nature and limitations of hypothetical economics that would begin to shape his theories. Veblen later developed an interest in the social sciences, taking courses within the fields of philosophy, natural history, and classical philology. Within the realm of philosophy, the works of Kant and Spencer were of greatest interest to him, inspiring several preconceptions of socio-economics. In contrast, his studies in natural history and classical philology shaped his formal use of the disciplines of science and language respectively.[10]

Veblen graduated in 1880 and subsequently traveled east to study philosophy and Johns Hopkins University. Unfortunately, however, he failed to obtain a scholarship and moved on to Yale University, where he hoped to receive some sort of financial aid. At Yale, he managed to find economic support for his studies and obtained his Ph.D. from the university in 1884 with a major in philosophy and a minor in social studies. His dissertation was entitled “Ethical Grounds of a Doctrine of Retribution”. During his time at Yale, he studied under renowned academics such as philosopher Noah Porter (1811–1892) and economist/sociologist William Graham Sumner (1840–1910).[11]

After some time spent at home on his family’s farm, Veblen returned to the world of academia to attend graduate school at Cornell University. During this time, he focused more on the social sciences.[12]

Academic career

After graduation from Yale in 1884, Veblen was essentially unemployed for seven years. Despite having strong letters of recommendation, he was unable to obtain a university position. Some have speculated that this was partially due to prejudice against Norwegians and others attribute this to the fact that most universities considered him insufficiently educated in Christianity.[13] Most academics at the time held divinity degrees, which Veblen did not have, leading university administrators to turn him away. It also did not help that he openly identified as an agnostic, which was uncommon at that time. As a result, Veblen returned to his family farm, a stay during which he had claimed to be recovering from malaria. He spent those years recovering and reading voraciously.[14]In 1891, Veblen left the farm to return to graduate school to study economics at Cornell University, under the guidance of an economics professor, James Laurence Laughlin. With the help of Professor Laughlin, who was moving to the University of Chicago, Veblen became a fellow at that university in 1892. Throughout his stay, he did much of the editorial work associated with The Journal of Political Economy, one of the many academic journals created during this time at the University of Chicago. Veblen used the journal as an outlet for his writings. His writings also began to appear in other journals, such as The American Journal of Sociology, another journal at the university. While he was mostly a marginal figure at the university, Veblen taught a number of classes at the college.[15]

In 1899, Veblen published his first and best-known book, titled The Theory of the Leisure Class. Despite this, his position at the University of Chicago remained unsubstantial. Upon his request for a customary raise of a few hundred dollars, because of the completion of his first book, the university’s president stated that he would not be upset if Veblen decided to leave the University of Chicago.[16] Notwithstanding, his book received much attention, and as a result, Veblen was eventually promoted to the position of assistant professor. Despite his growing fame, most of the students who took his courses were not fans of his supposedly dreadful teaching. It was noted that, by the end of the semester, few students remained as optimistic as they had been upon starting the semester. Veblen had also offended Victorian sentiments with his participation in extramarital affairs, and his days at the university dwindled in the next few years.[17]

In 1906, Veblen accepted the position of associate professor at Stanford University. Here he taught mostly undergraduate students, who felt similarly to his Chicago students and also noted his boring teaching style. In 1909, Veblen was ridiculed again for his tendencies both as a womanizer and an unfaithful husband. As a result, he was forced to resign from his position, which made it very difficult for him to find another academic position.[18]

With the help of Herbert Davenport, a friend who was the head of the economics department at the University of Missouri, Veblen accepted a position there in 1911. Veblen’s stay at Missouri was not one that he enjoyed. This was in part due to the fact that his position, as a lecturer, was of lower rank than his previous positions and of lower pay. Veblen also strongly disliked the town of Columbia, where the university was located.[19] While he may not have enjoyed his stay at Missouri, he did publish another of his best-known books, The Instinct of Workmanship and the State of the Industrial Arts, in 1914.

By 1917, Veblen moved to Washington, D.C. to work with a group that had been commissioned by President Woodrow Wilson to analyze possible peace settlements for World War I. This marked a series of distinct changes in his career path.[20] Following that, Veblen worked for the US Food Administration for a period of time. Shortly thereafter, Veblen moved to New York City to work as an editor for a magazine, The Dial. Within the next year, as the magazine shifted its orientation, he lost his editorial position.[21]

In the meantime, Veblen had made contacts with several other academics, such as Charles A. Beard, James Harvey Robinson, and John Dewey. The group of university professors and intellectuals eventually founded the New School for Social Research (known today as The New School) in 1919 as a modern, progressive free school where students could “seek an unbiased understanding of the existing order, its genesis, growth, and present working."[22] From 1919 to 1926, Veblen continued to write and maintain a role in The New School’s development. It was during this time that he wrote The Engineers and the Price System.[23]

Contributions to social theory

While Veblen mostly held positions in economics departments, his impacts on social theory were significant. The central problem for Veblen was the friction between "business" and "industry". Veblen identified "business" as the owners and leaders whose primary goal was the profits of their companies but, in an effort to keep profits high, often made efforts to limit production. By obstructing the operation of the industrial system in that way, "business" negatively affected society as a whole (through higher rates of unemployment, for example). With that said, Veblen identified business leaders as the source of many problems in society, which he felt, should be led by people such as engineers, who understood the industrial system and its operation, while also having an interest in the general welfare of society at large.Conspicuous Consumption

Within Veblen’s most famous work, The Theory of the Leisure Class, he writes critically of the leisure class for its role in fostering wasteful consumption. It is within this first work that Veblen coined the term "conspicuous consumption", which is defined as the act of spending more money on goods than they are worth. The term originated during a time when a nouveau riche social class emerged as a result of the accumulation of capital wealth during the Second Industrial Revolution. Veblen identifies the leisure class as members of society who engage in "conspicuous leisure", or the non-productive use of time for the sake of displaying social status. He explains that members of the leisure class, often associated with business, are those who also engage in conspicuous consumption in order to impress the rest of society through the manifestation of their social power and prestige, be it real or perceived. In other words, social status, Veblen explained, becomes earned and displayed by patterns of consumption rather than what the individual does or does not make financially. Subsequently, people in all other social classes are influenced by this behavior and, as Veblen argued, strive to emulate the leisure class. What results from this behavior, is a society characterized by the waste of time and money. Unlike many other sociological works of the time, The Theory of the Leisure Class focused on the notion of consumption, rather than production. It can be argued that Veblen’s writing marked a shift from such focus on production to an emphasis on consumption.Veblen's economics

Veblen and other American institutionalists were indebted to the German Historical School, especially Gustav von Schmoller, for the emphasis on historical fact, their empiricism and especially a broad, evolutionary framework of study.[24][25] Veblen admired Schmoller, but criticized some other leaders of the German school because of their overreliance on descriptions, long displays of numerical data and narratives of industrial development that rested on no underlying economic theory. Veblen tried to use the same approach with his own theory added.[26]Probably the clearest inheritors of Veblen's ideas that humans are not rationally pursuing value and utility through their conspicuous consumption are adherents of the school of behavioral economics, who study the ways consumers and producers act against their own interests in apparently non-rational ways.

Veblen developed a 20th-century evolutionary economics based upon Darwinian principles and new ideas emerging from anthropology, sociology, and psychology. Unlike the neoclassical economics that was emerging at the same time, Veblen described economic behavior as socially determined and saw economic organization as a process of ongoing evolution. Veblen strongly rejected any theory based on individual action or any theory highlighting any factor of an inner personal motivation. Such theories were according to him "unscientific". This evolution was driven by the human instincts of emulation, predation, workmanship, parental bent, and idle curiosity. Veblen wanted economists to grasp the effects of social and cultural change on economic changes. In The Theory of the Leisure Class, the instincts of emulation and predation play a major role. People, rich and poor alike, attempt to impress others and seek to gain advantage through what Veblen termed "conspicuous consumption" and the ability to engage in “conspicuous leisure”. In this work Veblen argued that consumption is used as a way to gain and signal status. Through "conspicuous consumption" often came "conspicuous waste", which Veblen detested.

In The Theory of Business Enterprise, which was published in 1904 during the height of American concern with the growth of business combinations and trusts, Veblen employed his evolutionary analysis to explain these new forms. He saw them as a consequence of the growth of industrial processes in a context of small business firms that had evolved earlier to organize craft production. The new industrial processes impelled integration and provided lucrative opportunities for those who managed it. What resulted was, as Veblen saw it, a conflict between businessmen and engineers, with businessmen representing the older order and engineers as the innovators of new ways of doing things. In combination with the tendencies described in The Theory of the Leisure Class, this conflict resulted in waste and "predation" that served to enhance the social status of those who could benefit from predatory claims to goods and services.

Veblen generalized the conflict between businessmen and engineers by saying that human society would always involve conflict between existing norms with vested interests and new norms developed out of an innate human tendency to manipulate and learn about the physical world in which we exist. He also generalized his model to include his theory of instincts, processes of evolution as absorbed from Sumner, as enhanced by his own reading of evolutionary science, and pragmatic philosophy first learned from Peirce. The instinct of idle curiosity led humans to manipulate nature in new ways and this led to changes in what he called the material means of life. Because, as per the pragmatists, our ideas about the world are a human construct rather than mirrors of reality, changing ways of manipulating nature lead to changing constructs and to changing notions of truth and authority as well as patterns of behavior (institutions). Societies and economies evolve as a consequence, but do so via a process of conflict between vested interests and older forms and the new. Veblen never wrote with any confidence that the new ways were better ways, but he was sure in the last three decades of his life that the American economy could, in the absence of vested interests, have produced more for more people. In the years just after World War I he looked to engineers to make the American economy more efficient.

In addition to The Theory of the Leisure Class and The Theory of Business Enterprise, Veblen's monograph "Imperial Germany and the Industrial Revolution", and his many essays, including "Why is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science", and "The Place of Science in Modern Civilization", remain influential.

Personal Life

Marriages

The two primary relationships that Veblen had were with his first two wives respectively, although he was known for his tendency to engage in extramarital affairs throughout his life.During his time at Carleton, Veblen met his first wife, Ellen Rolfe, the niece of the college president. They married in 1888. While some scholars have attributed his womanizing tendencies to the couple’s numerous separations and eventual divorce in 1911, others have speculated that the relationship's demise was rooted in Ellen’s inability to bear children. Following her death in 1926, it was revealed that she had asked for her autopsy to be sent to Veblen, her then ex-husband. The autopsy showed that Ellen’s reproductive parts had not developed normally, and she had been unable to bear children.[27] A book written by Veblen’s stepdaughter asserted that “this explained her disinterest in a normal wifely relationship with Thorstein” and that he “treated her more like a sister, a loving sister, than a wife”.[28]

Veblen married Ann Bradley Bevans, a former student, in 1914 and became stepfather to her two girls, Becky and Ann. For the most part, it appears that they had a happy marriage. Ann was described by her daughter as a suffragette, a socialist, and a staunch advocate of unions and workers' rights. A year after he married Ann, they were expecting a child together, however, the pregnancy ended in a miscarriage. Veblen never had any children of his own.[29]

Death

After his wife Ann's premature death in 1920, Veblen became active in the care of his stepdaughters. Becky went with him when he moved to California, looked after him there, and was with him at his death in 1929.[30] He died in August 1929, just a few months shy of the Great Depression, the economic crisis that he anticipated in Absentee Ownership: Business Enterprise in Recent Times.[31]Veblen's intellectual legacy

In spite of difficulties of sometimes archaic language, caused in large part by Veblen's struggles with the terminology of unilinear evolution and of biological determination of social variation[citation needed] that still dominated social thought when he began to write, Veblen's work remains relevant, and not simply for the phrase “conspicuous consumption”. His evolutionary approach to the study of economic systems is once again in vogue and his model of recurring conflict between the existing order and new ways can be of great value in understanding the new global economy.The handicap principle of evolutionary sexual selection is often compared to Veblen's “conspicuous consumption”.[32]

Veblen, as noted, is regarded as one of the co-founders (with John R. Commons, Wesley C. Mitchell, and others) of the American school of institutional economics. Present-day practitioners who adhere to this school organise themselves in the Association for Evolutionary Economics (AFEE) and the Association for Institutional Economics (AFIT). AFEE gives an annual Veblen-Commons (see John R. Commons) award for work in Institutional Economics and publishes the Journal of Economic Issues. Some unaligned practitioners include theorists of the concept of "differential accumulation".[33]

Veblen is cited in works of feminist economists.[34]

Veblen's work has also often been cited in American literary works. He is featured in The Big Money by John Dos Passos and mentioned in Carson McCullers' The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter.

One of Veblen's Ph.D. students was George W. Stocking, Sr., a pioneer in the emerging field of industrial organization economics.

Another of Veblen's Ph.D. students was Canadian academic and author Stephen Leacock, who went on to become the head of Department of Economics and Political Science at McGill University. Influence of Theory of the Leisure Class can be seen in Leacock's 1914 satire, Arcadian Adventures with the Idle Rich.

Quotes

“Conspicuous consumption of valuable goods is a means of reputability to the gentleman of leisure.”-Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class

“The institution of a leisure class has emerged gradually during the transition from primitive savagery to barbarism; or more precisely, during the transition from a peaceable to a consistently warlike habit of life.”

-Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class

“However widely, or equally, or ‘fairly’, it may be distributed, no general increase of the community’s wealth can make any approach to satiating this need, the ground of which is the desire of every one to excel every one else in the accumulation of goods.”

-Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class

“Leisure held the first place at the start, and came to hold a rank very much above the wasteful consumption of goods…From that point onward, consumption has gained ground, until, at present, it unquestionably holds the primacy.”

-Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class

“It is much more difficult to recede from a scale of expenditure once adopted than it is to extend the accustomed scale in response to an accession of wealth.”

-Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class

“As increased industrial efficiency makes it possible to procure the means of livelihood with less labor, the energies of the industrious members of the community are bent to the compassing of a higher result in conspicuous expenditure, rather than slackened to a more comfortable pace.”

-Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class

“The requirement of conspicuous wastefulness is…present as a constraining norm selectively shaping and sustaining our sense of what is beautiful.”

-Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class

“The superior gratification from the use and contemplation of costly and supposedly beautiful products is, commonly, in great measure a gratification of our sense of costliness masquerading under the name of beauty.”

-Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class

“Born in iniquity and conceived in sin, the spirit of nationalism has never ceased to bend human institutions to the service of dissension and distress.”

-Veblen, Absentee Ownership: Business Enterprise In Recent Times

“It is always sound business to take any obtainable net gain, at any cost, and at any risk to the rest of the community.”

-Veblen, Absentee Ownership: Business Enterprise in Recent Times

Major works

Books

- Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions 1899, 1915 edition at Internet Archive

- Theory of Business Enterprise 1904, at Internet Archive

- The Instincts of Worksmanship and the State of the Industrial Arts, 1914.

- Imperial Germany and the Industrial Revolution 1915.

- The Higher Learning In America: A Memorandum On the Conduct of Universities By Business Men 1918, at Internet Archive

- An Inquiry Into The Nature Of Peace And The Terms Of Its Perpetuation pdf 1919, at Internet Archive

- The Place of Science in Modern Civilisation and Other Essays 1919, at Internet Archive

- The Vested Interests and the Common Man pdf 1919, on Open Library

- The Engineers and the Price System 1921, at Internet Archive

- Absentee Ownership and Business Enterprise in Recent Times: the case of America, 1923.

- Essays in Our Changing Order, 1927.

- What Veblen Taught: Selected Writings of Thorstein Veblen edited by Wesley C. Mitchell; 1936.

Articles

- "Kant's Critique of Judgement", Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 1884.

- "Some Neglected Points in the Theory of Socialism", Annals of AAPSS 1891.

- "Bohm-Bawerk's Definition of Capital and the Source of Wages", QJE, 1892, .

- "The Overproduction Fallacy", QJE, 1892.

- "The Food Supply and the Price of Wheat", JPE, 1893.

- "The Army of the Commonweal", JPE, 1894.

- "The Economic Theory of Women's Dress", Popular Science Monthly, 1894.

- "Review of Karl Marx's Poverty of Philosophy", JPE, 1896.

- "Review of Werner Sombart's Sozialismus", JPE, 1897.

- "Review of Gustav Schmoller's Über einige Grundfragen der Sozialpolitik", JPE, 1898.

- "Review of Turgot's Reflections", JPE, 1898.

- "Why is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science?", QJE, 1898.

- "The Beginnings of Ownership", American Journal of Sociology, 1898.

- "The Instinct of Workmanship and the Irksomeness of Labor", American Journal of Sociology, 1898.

- "The Barbarian Status of Women", American Journal of Sociology, 1898.

- "The Preconceptions of Economic Science", QJE1899,1900. Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

- "Industrial and Pecuniary Employments", Publications of the AEA, 1901.

- "Gustav Schmoller's Economics", QJE, 1901.

- "Arts and Crafts", JPE, 1902.

- "Review of Werner Sombart's Der moderne Kapitalismus", JPE, 1903.

- "Review of J.A. Hobson's Imperialism", JPE, 1903.

- "An Early Experiment in Trusts", JPE, 1904.

- "Review of Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations", JPE, 1904.

- "Credit and Prices", JPE, 1905.

- "The Place of Science in Modern Civilization", American J of Sociology, 1906.

- "Professor Clark's Economics", QJE, 1906.

- "The Socialist Economics of Karl Marx and His Followers", (1906,1907), QJE.

- "Fisher's Capital and Income", Political Science Quarterly, 1907.

- "The Evolution of the Scientific Point of View", University of California Chronicle.

- "On the Nature of Capital", 1908, QJE, 1908.

- "Fisher's Rate of Interest", Political Science Quarterly, 1909.

- "The Limitations of Marginal Utility", JPE, 1909.

- "Christian Morals and the Competitive System", International J of Ethics, 1910.

- "The Mutation Theory and the Blond Race", Journal of Race Development, 1913.

- "The Blond Race and the Aryan Culture", Univ of Missouri Bulletin, 1913.

- "The Opportunity of Japan", Journal of Race Development, 1915.

- "On the General Principles of a Policy of Reconstruction", J of the National Institute of Social Sciences, 1918.

- "Passing of National Frontiers", Dial, 1918.

- "Menial Servants during the Period of War", Public, 1918.

- "Farm Labor for the Period of War", Public, 1918.

- "The War and Higher Learning", Dial, 1918.

- "The Modern Point of View and the New Order", Dial, 1918.

- "The Intellectual Pre-Eminence of Jews in Modern Europe", Political Science Quarterly, 1919.

- "On the Nature and Uses of Sabotage", Dial, 1919.

- "Bolshevism is a Menace to the Vested Interests", Dial, 1919.

- "Peace", Dial, 1919.

- "The Captains of Finance and the Engineers", Dial, 1919.

- "The Industrial System and the Captains of Industry", Dial, 1919.

- The Place of Science in Modern Civilization and other essays, 1919.

- "Review of J.M.Keynes's Economic Consequences of the Peace, Political Science Quarterly, 1920.

- "Economic theory in the Calculable Future", AER, 1925.

- "Introduction" in The Laxdaela Saga, 1925.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered