Sandra Day O'Connor

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Sandra Day O'Connor | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office September 21, 1981 – January 31, 2006 |

|

| Appointed by | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | Potter Stewart |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Alito |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Sandra Day March 26, 1930 (age 83) El Paso, Texas, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | John O'Connor (1952–2009) (his death) |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Stanford University (B.A, J.D) |

| Religion | Episcopal |

| Signature | |

Prior to O'Connor's appointment to the Court, she was an elected official and judge in Arizona serving as the first female Majority Leader in the United States as the Republican leader in the Arizona Senate.[2] On July 1, 2005, she announced her intention to retire effective upon the confirmation of a successor.[3] Samuel Alito was nominated to take her seat in October 2005, and joined the Court on January 31, 2006.

Considered a federalist and a moderate conservative, O'Connor tended to approach each case narrowly without arguing for sweeping precedents. She most frequently sided with the court's conservative bloc, although in the latter years of her tenure, she was regarded as having the swing opinion in many cases. Her unanimous confirmation by the Senate in 1981 was supported by most conservatives, led by Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, and liberals, including Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy and women's rights groups like the National Organization for Women.

O'Connor was Chancellor of The College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, and currently serves on the board of trustees of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Several publications have named O'Connor among the most powerful women in the world.[4][5] On August 12, 2009, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor of the United States, by President Barack Obama.

Contents

Early life and education

She was born in El Paso, Texas, to Harry Alfred Day, a rancher, and Ada Mae (Wilkey).[6] She grew up on a cattle ranch near Duncan, Arizona. She later wrote a book with her brother, H. Alan Day, Lazy B : Growing up on a Cattle Ranch in the American West (2002), about her childhood experiences on the ranch. For most of her early schooling, O'Connor lived in El Paso with her maternal grandmother, and attended public schools and the Radford School for Girls, a private school. She graduated sixth in her class at Austin High School in El Paso in 1946.[7] She attended Stanford University, where she received her B.A. in economics in 1950. She continued at the Stanford Law School for her LL.B.. There, she served on the Stanford Law Review with its presiding editor in chief, future Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist, who was the class valedictorian,[8] and whom she briefly dated during law school.[9] She has stated that she graduated third in her law school class,[10] although Stanford's official position is that the law school did not rank students in 1952.[11]On December 20, 1952, six months after graduating from law school, she married John Jay O'Connor III. They had three sons: Scott, Brian, and Jay. Her husband suffered from Alzheimer's disease for nearly twenty years until his death in 2009,[12] and she has become involved in raising awareness of the disease.

After graduation from law school, at least 40 law firms refused to interview her for a position as an attorney because she was a woman.[13] She eventually found employment as a deputy county attorney in San Mateo, California, after she offered to work for no salary and without an office, sharing space with a secretary.[13]

O'Connor served as Assistant Attorney General of Arizona 1965–69 until she was appointed to fill a vacancy in the Arizona State Senate. She was re-elected to the State Senate in 1973 and became the first woman to serve as its Majority Leader. In 1975 she was elected to the Maricopa County Superior Court and in 1979 was elevated to the Arizona State Court of Appeals. She served on the Court of Appeals until 1981 when she was appointed to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court career

Appointment

Supreme Court Justice-nominee Sandra Day O'Connor talks with President Ronald Reagan outside the White House, July 15, 1981.

Reagan wrote in his diary on July 6, 1981: "Called Judge O'Connor and told her she was my nominee for supreme court. Already the flak is starting and from my own supporters. Right to Life people say she is pro abortion. She says abortion is personally repugnant to her. I think she'll make a good justice."[20] On September 21, O'Connor was confirmed by the U.S. Senate with a decision of 99–0;[15] Senator Max Baucus of Montana was absent for the decision, and sent O'Connor a copy of A River Runs Through It by way of apology.[21] In her first year on the Court she received over 60,000 letters from the public, more than any other justice in history.

Response to being first woman on the Supreme Court

In response to a carelessly written editorial in The New York Times which mentioned the "nine old men" of the Court,[citation needed] the self-styled FWOTSC (First Woman On The Supreme Court) sent a pithy letter to the editor:| “ | I noticed the following ....:

|

” |

—Sandra D. O'Connor, Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, October 12, 1983, "High Court's '9 Men' Were a Surprise to One", The New York Times, October 5, 1983 re: (First Woman On The Supreme Court); William Safire, "On Language; Potus and Flotus", The New York Times Magazine, October 12, 1997. Retrieved December 7, 2007

|

||

Supreme Court jurisprudence

Voting record and deciding votes

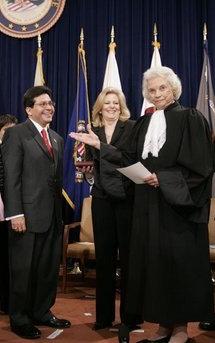

Justice O'Connor presents Alberto Gonzales to the audience after swearing him in as U.S. Attorney General, as Mrs. Becky Gonzales looks on.

Later on, as the Court's make-up became more conservative (e.g., Anthony Kennedy replacing Lewis Powell, and Clarence Thomas replacing Thurgood Marshall), O'Connor often became the swing vote on the Court. However, she usually disappointed the Court's more liberal bloc in contentious 5–4 decisions: from 1994 to 2004, she joined the traditional conservative bloc of Rehnquist, Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy, and Thomas 82 times; she joined the liberal bloc of John Paul Stevens, David Souter, Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer only 28 times.[25]

O'Connor's relatively small[26] shift away from conservatives on the Court seems to have been due at least in part to Thomas's views.[27] When Thomas and O'Connor were voting on the same side, she would typically write a separate opinion of her own, refusing to join his.[28] In the 1992 term, O'Connor did not join a single one of Thomas' dissents.[29]

Willamette University College of Law Professor Steven Green, who served for nine years as general counsel for Americans United for Separation of Church and State and has argued before the Court numerous times stated, "She was a moderating voice on the court and was very hesitant to expand the law in either direction." Green also noted that, unlike some other Court justices, O'Connor "[s]eemed to look at each case with an open mind".[30]

Some of the cases in which O'Connor was the deciding vote include:

- McConnell v. FEC, 540 U.S. 93 (2003)

- This ruling upheld the constitutionality of most of the McCain-Feingold campaign-finance bill regulating "soft money" contributions.

- Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003) and Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003)

- O'Connor wrote the opinion of the court in Grutter and joined the majority in Gratz. In this pair of cases, the University of Michigan's undergraduate admissions program was held to have engaged in unconstitutional reverse discrimination, but the more-limited type of affirmative action in the University of Michigan Law School's admissions program was held to have been constitutional.

- Lockyer v. Andrade, 538 U.S. 63 (2003)

- O'Connor wrote the majority opinion, with the four conservative justices concurring, that a 50 year sentence without parole for petty shoplifting a few children's videotapes under California's three strikes law was not cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment because there was no "clearly established" law to that effect. Leandro Andrade, a Latino nine year Army veteran and father of three, will be eligible for parole in 2046 at age eighty-seven.

- Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639 (2002)

- O'Connor joined the majority holding that the use of school vouchers for religious schools did not violate the First Amendment's Establishment Clause.

- Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640 (2000)

- O'Connor joined the majority in holding that New Jersey violated the Boy Scouts' freedom of association by prohibiting it from selecting its troop leaders on the basis of sexual orientation.

- United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995)

- O'Connor joined a majority holding unconstitutional Gun-Free School Zones Act as beyond Congress's Commerce Clause power.

- Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000)

- O'Connor joined with four other justices on December 12, 2000, to rule on the Bush v. Gore case that ceased challenges to the results of the 2000 presidential election (ruling to stop the ongoing Florida election recount and to allow no further recounts). This case effectively ended Gore's hopes to become president. Some legal scholars have argued that she should have recused herself from this case, citing several reports that she became upset when the media initially announced that Gore had won Florida, with her husband explaining that they would have to wait another four years before retiring to Arizona.[31]

- Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, 492 U.S. 490 (1989)

- This decision upheld as constitutional state restrictions on second trimester abortions that are not necessary to protect maternal health, contrary to the original trimester requirements in Roe v. Wade. Although O'Connor joined the majority, which also included Rehnquist, Scalia, Kennedy and Byron White, in a concurring opinion she refused to explicitly overturn Roe.

- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003)

- O'Connor wrote a concurring opinion contending that state laws that prohibited homosexual sodomy, but not heterosexual sodomy, violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Although she agreed with the majority in holding such laws unconstitutional, she did not join in the opinion that they violated the substantive due process afforded by the Due Process Clause. Under a ruling under the Equal Protection Clause, states could still prohibit sodomy, provided they prohibited both homosexual sodomy and heterosexual sodomy.

Fourth Amendment

According to George Washington University law professor Jeffrey Rosen, "O'Connor was an eloquent opponent of intrusive group searches that threatened privacy without increasing security. In a 1983 opinion upholding searches by drug-sniffing dogs, she recognized that a search is most likely to be considered constitutionally reasonable if it is very effective at discovering contraband without revealing innocent but embarrassing information."[32] Howard University law professor Andrew Taslitz, referencing O'Connor's dissent in a 2001 case, said of her Fourth Amendment jurisprudence: "O'Connor recognizes that needless humiliation of an individual is an important factor in determining Fourth Amendment reasonableness."[33]Cases involving minorities

From her start on the Court until 1998, O'Connor voted against the minority litigant in all but two of the forty-one close cases involving race.[34]In the 1990 and 1995 Missouri v. Jenkins rulings, O'Connor voted with the majority that district courts had no authority to require the state of Missouri to increase school funding in order to counteract racial inequality. In the 1991 Freeman v. Pitts case, O'Connor joined a concurring opinion in a plurality, agreeing that a school district that had formerly been under judicial review for racial segregation could be freed of this review, even though not all desegregation targets had been met. Law professor Herman Schwartz criticized these rulings, writing that in both cases "both the fact and effects of segregation were still present."[34]

In 1987's McCleskey v. Kemp, O'Connor joined a 5–4 majority that voted to uphold the death penalty for an African American man, Warren McCleskey, convicted of killing a white police officer, despite statistical evidence that black defendants were more likely to receive the death penalty than others both in Georgia and in the U.S. as a whole.[34][35][36]

In 1996's Shaw v. Hunt and Shaw v. Reno, O'Connor joined a Rehnquist opinion, following an earlier path-breaking decision she authored in 1993, in which the court struck down an electoral districting plan designed to facilitate the election of two black representatives out of twelve from North Carolina, a state that had not had any black representative since Reconstruction, despite being approximately 20% black[34]—the Court held that the districts were unacceptably gerrymandered and O'Connor called the odd shape of the district in question, North Carolina's 12th, "bizarre".

Law Professor Herman Schwartz called O'Connor "the Court’s leader in its assault on racially oriented affirmative action,"[34] although she joined with the Court in upholding the constitutionality of race-based admissions to universities.[14]

In late 2008, O'Connor said she believed racial affirmative action should continue to help heal the inequalities created by racial discrimination. She stressed this wouldn't be a cure-all but rather a bandage and that society has to do much more to correct our racial imbalance. In 2003 Justice O'Connor authored a majority Supreme Court opinion (Grutter v. Bollinger) saying racial affirmative action wouldn't be constitutional permanently but long enough to correct past discrimination ─ an approximation limit of around 25 years, or until 2028.[37]

Abortion

The four women who have served on the Court (from left to right: O'Connor and Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Elena Kagan) on October 1, 2010, prior to Justice Kagan's Investiture Ceremony.

O'Connor allowed certain limits to be placed on access to abortion, but supported the fundamental right to abortion protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey, O'Connor used a test she had originally developed in City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health to limit the holding of Roe v. Wade, opening up a legislative portal where a State could enact measures so long as they did not place an "undue burden" on a woman's right to an abortion. Casey revised downward the standard of scrutiny federal courts would apply to state abortion restrictions, a major departure from Roe. However it preserved Roe's core constitutional precept: that the Fourteenth Amendment protects the fundamental right to control one's reproductive destiny. Writing the plurality opinion for the Court, O'Connor, along with Justices Kennedy and Souter, famously declared: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life. Beliefs about these matters could not define the attributes of personhood were they formed under compulsion of the State.” Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833, 851 (1992).

Foreign law

O'Connor was a vigorous defender of the citing of foreign laws in judicial decisions. In a well-publicized October 28, 2003, speech at the Southern Center for International Studies, O'Connor said:The impressions we create in this world are important and can leave their mark ... [T]here is talk today about the "internationalization of legal relations". We are already seeing this in American courts, and should see it increasingly in the future. This does not mean, of course, that our courts can or should abandon their character as domestic institutions. But conclusions reached by other countries and by the international community, although not formally binding upon our decisions, should at times constitute persuasive authority in American courts—what is sometimes called "transjudicialism".[40]In the speech she noted the 2002 Court case, Atkins v. Virginia, in which the majority decision (which included her) cited disapproval of the death penalty in Europe as part of its argument. This speech, and the general concept of relying on foreign law and opinion, was widely criticized by conservatives.[41] In May 2004, the U.S. House of Representatives responded by passing a non-binding resolution, the "Reaffirmation of American Independence Resolution", stating that "U.S. judicial decisions should not be based on any foreign laws, court decisions, or pronouncements of foreign governments unless they are relevant to determining the meaning of American constitutional and statutory law."[42]

O'Connor once quoted the constitution of the Middle Eastern nation of Bahrain, which states that "[n]o authority shall prevail over the judgement of a judge, and under no circumstances may the course of justice be interfered with." Further, "[i]t is in everyone's interest to foster the rule-of-law evolution." O'Connor proposed that such ideas be taught in American law schools, high schools and universities. Critics contend that such thinking is contrary to the U.S. Constitution and establishes a rule of man, rather than law.[40] In her retirement, she has continued to speak and organize conferences on the issue of judicial independence.

Conservative criticism

O'Connor's case-by-case approach routinely placed her in the center of the court and drew both criticism and praise. The Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer, for instance, described her as lacking a judicial philosophy and instead displaying "political positioning embedded in a social agenda".[43] Another conservative commentator, Ramesh Ponnuru, wrote that, although O'Connor "has voted reasonably well", her tendency to issue very case-specific rulings "undermines the predictability of the law and aggrandizes the judicial role".[44]Christian heritage

In 1989, a letter O'Connor wrote regarding three Court rulings on Christian heritage was used by a group of conservative Arizona Republicans in their claim that America was a "Christian nation". O'Connor, an Episcopalian, said, "[i]t was not my intention to express a personal view on the subject of the inquiry."'[45]Retirement

O'Connor was successfully treated for breast cancer in 1988 (she also had her appendix removed that year). One side effect of this experience was that there was perennial speculation over the next seventeen years that she might retire from the Court.On December 12, 2000, The Wall Street Journal reported that O'Connor was reluctant to retire with a Democrat in the presidency:

| “ | At an Election Night party at the Washington, D.C. home of Mary Ann Stoessel, widow of former Ambassador Walter Stoessel, the justice's husband, John O'Connor, mentioned to others her desire to step down, according to three witnesses. But Mr. O'Connor said his wife would be reluctant to retire if a Democrat were in the White House and would choose her replacement. Justice O'Connor declined to comment.[46] | ” |

On July 19, Bush nominated D.C. Circuit Judge John G. Roberts, Jr. to succeed O'Connor. O'Connor heard the news over the car radio on the way back from a fishing trip.[citation needed] She felt he was an excellent and highly qualified choice — he had argued numerous cases before the Court during her tenure.[citation needed] However, she was terribly disappointed her replacement was not a woman.[47]

On July 21, O'Connor spoke to a Ninth Circuit conference and blamed the televising of Senate Judiciary Committee hearings for escalated conflicts over judges. She expressed sadness over attacks on the independent judiciary, and praised President Reagan for opening doors for women.[citation needed] O'Connor had been expected to leave the Court before the next term started on October 3, 2005. However, Rehnquist died on September 3 (she spoke at his funeral). Two days later, Bush withdrew Roberts as his nominee for her seat and instead appointed him to fill the vacant office of Chief Justice. O'Connor agreed to stay on the Court until her replacement was confirmed. On October 3, Bush nominated White House Counsel Harriet Miers to replace O'Connor. After much criticism and controversy over her nomination, on October 27, Miers asked Bush to withdraw her nomination. Bush accepted her request later the same day. On October 31, Bush nominated Third Circuit Judge Samuel Alito to replace O'Connor; Alito was confirmed and sworn in on January 31, 2006.

O'Connor's last Court opinion, Ayotte v. Planned Parenthood of New England, written for a unanimous court, was a procedural decision that involved abortion.

She stated that she plans to travel, spend time with family, and, because of her fear of the attacks on judges by legislators, will work with the American Bar Association on a commission to help explain the separation of powers and the role of judges. She has also announced that she is working on a new book, which will focus on the early history of the Court. She is currently a trustee on the board of the Rockefeller Foundation. She would have preferred to stay on the Court for several more years until she was ill and "really in bad shape" but stepped down to spend more time with her husband, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease previous to his death in 2009. O'Connor said it was her plan to follow the tradition of previous justices, who enjoy lifetime appointments. "Most of them get ill and are really in bad shape, which I would've done at the end of the day myself, I suppose, except my husband was ill and I needed to take action there."'[48]

As of August 2009, she continues to hear cases and has rendered over a dozen opinions in federal appellate courts across the country, filling in as a substitute judge when vacations or vacancies leave their three-member panels understaffed.[49]

Since retiring, O'Connor has reflected on her time on the Supreme Court by saying that she regrets the court hearing the Bush v. Gore case in 2000 because it "stirred up the public" and "gave the court a less-than-perfect reputation." The former justice told the Chicago Tribune that "Maybe the court should have said, 'We’re not going to take it, goodbye,’...It turned out the election authorities in Florida hadn’t done a real good job there and kind of messed it up. And probably the Supreme Court added to the problem at the end of the day.”[50]

Post-Supreme Court career

O'Connor in 2008 with then Harvard Law School Dean Elena Kagan. Kagan is the fourth female Justice on the Court.

| This article is in a list format that may be better presented using prose. (September 2009) |

Commentary

On March 9, 2006, during a speech at Georgetown University, O'Connor said some political attacks on the independence of the courts pose a direct threat to the constitutional freedoms of Americans. She said "any reform of the system is debatable as long as it is not motivated by "nakedly partisan reasoning" retaliation because congressmen or senators dislike the result of the cases. Courts interpret the law as it was written, not as the congressmen might have wished it was written, and "it takes a lot of degeneration before a country falls into dictatorship, but we should avoid these ends by avoiding these beginnings."[51] On September 19, 2006, she echoed her concerns for an independent judiciary during the dedication address at the Elon University School of Law.On September 28, 2006, O'Connor co-hosted and spoke at a conference at Georgetown University Law Center, Fair and Independent Courts: A Conference on the State of the Judiciary.[52][53]

Judge William H. Pryor, Jr., a conservative jurist, has criticized O'Connor's speeches and op-eds for hyperbole and factual inaccuracy, based in part on O'Connor's opinions as to whether judges face a rougher time in the public eye today than in the past.[54][55]

On November 7, 2007, at a conference on her landmark opinion in Strickland v. Washington (1984) sponsored by the Constitution Project, O'Connor urged the creation of a system for "merit selection for judges". She also highlighted the lack of proper legal representation for many of the poorest defendants.[56]

On August 7, 2008, O'Connor and Abdurrahman Wahid, the former President of Indonesia, wrote an editorial in the Financial Times stating their concerns about the threatened imprisonment of Malaysian opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim.[57]

On November 19, 2008, O'Connor published an introductory essay to a themed issue on judicial accountability in the Denver University Law Review. She calls for a better public understanding of judicial accountability.[58]

On January 26, 2010 O'Connor issued her own polite public dissent to the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision on corporate political spending, telling law students that the court has created an unwelcome new path for wealthy interests to exert influence on judicial elections.[59]

Activities and memberships

As a Retired Supreme Court Justice (roughly equivalent to senior status for judges of lower federal courts), O'Connor has continued to receive a full salary, maintain a staffed office with at least one law clerk, and to hear cases on a part-time basis in federal district courts and courts of appeals as a visiting judge. However, conservative commentator Ed Whelan has questioned whether O'Connor is constitutionally entitled to act as a federal judge following her resignation: "In short, O’Connor resigned and became a former justice; she did not just take 'senior status.' Therefore, she was no longer a federal judge at all and has not been constitutionally eligible to serve as a judge."[60]In 2003, she wrote a book titled The Majesty of the Law: Reflections of a Supreme Court Justice (ISBN 0-375-50925-9).

On October 4, 2005, President Gene Nichol of the College of William & Mary announced that O'Connor had accepted[61] the largely ceremonial role of becoming the 23rd Chancellor of the College, replacing Henry Kissinger, and following in the position held by Margaret Thatcher, Chief Justice Warren Burger, and President George Washington. The Investiture Ceremony was held April 7, 2006. O'Connor continues to make semi-regular visits to the college.

In 2005, she wrote a children's book, Chico (ISBN 0-525-47452-8), which gives an autobiographical description of her childhood.

O'Connor was a member of the 2006 Iraq Study Group, appointed by the U.S. Congress.[62]

On May 15, 2006, O'Connor gave the commencement address at the William & Mary School of Law, where she said that judicial independence is "under serious attack at both the state and national level".[63]

As of Spring 2006, O'Connor teaches a two-week course called "The Supreme Court" at the University of Arizona's James E. Rogers College of Law every spring semester.

In October 2006, O'Connor sat as a member of panels of the United States Courts of Appeals for the Second, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits, to hear arguments in one-day's cases in each court.[64]

O'Connor chaired the Jamestown 2007 celebration, commemorating the 400th anniversary of the founding of the colony at Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. Her appearances in Jamestown dovetailed with her appearances and speeches as chancellor at The College of William & Mary nearby. In the fall of 2007, O'Connor and W. Scott Bales taught a course at the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law at Arizona State University.

In 2008, O'Connor was named an inaugural Harry Rathbun Visiting Fellow by the Office for Religious Life at Stanford University. On April 22, 2008, she gave "Harry's Last Lecture on a Meaningful Life" in honor of the former Stanford Law professor who shaped her undergraduate and law careers.[65]

In February 2009, O'Connor launched Our Courts, a website she created to offer interactive civics lessons to students and teachers because she was concerned about the lack of knowledge among most young Americans about how their government works. On March 3, 2009, O'Connor appeared on the satirical television program The Daily Show with Jon Stewart to promote the website. In August 2009, http://ourcourts.org/ added two online interactive games.[66] The initiative expanded, becoming iCivics in May 2010, and continues to offer free lessons plans, games, and interactive videogames for middle and high school educators.[67] During the inauguration of Mesa Municipal Court on April 16, 2010, she gracefully received a blessed garland – along with a copy of Bhagavad-Gītā As It Is[68] from Dr. Prayag Narayan Misra – a Hare Krishna devotee.[69]

She currently serves on the Board of Trustees of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, which is a museum dedicated to the U.S. Constitution.[70]

In 2013, she wrote "Out of Order: Stories from the History of the Supreme Court", a book containing stories from the history of the Supreme Court.[71]

In April 2013, the Board of Directors of Justice at Stake, a nonpartisan national partnership of more than 50 organizations that focuses exclusively on keeping courts fair and impartial, announced that O'Connor would be joining the organization as Honorary Chair. “The greatest threat to judicial independence in our country today is the flood of money coming into the courtrooms by increasingly expensive and volatile campaigns,” Justice O’Connor said in a press release. “Justice at Stake is a nonpartisan partnership that has done groundbreaking work. I’ve worked with Justice at Stake in the past. I’m happy now to help raise its profile in protecting fair courts around the country.”[72]

Legacy, awards

- The federal courthouse in Phoenix, dedicated in 2000, is named in her honor.[73]

- In 1985, she received the Elizabeth Blackwell Award, an award presented periodically to a woman who has demonstrated "outstanding service to humankind", from Hobart and William Smith Colleges.

- In 1998, O'Connor was awarded the Mary Harriman Community Leadership award by The Association of Junior Leagues International, Inc. for her work supporting bilingual education, repealing "women's work" laws that prohibited the number of hours women could work and reforming Arizona's marital laws to make marriage more equitable for women. O'Connor is a member of the Junior League of Phoenix and served as the League's President from 1966 to 1967.

- In 2002, O'Connor was inducted into the National Cowgirl Hall of Fame in Fort Worth.[74]

- On July 4, 2003, the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia awarded O'Connor the Liberty Medal. In her acceptance speech she stated, "one of our greatest judges, Learned Hand, explained:

'Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women. When it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it.' But our understanding today must go beyond the recognition that ‘liberty lies in (our) hearts’ to the further recognition that only citizens with knowledge about the content and meaning of our constitutional guarantees of liberty are likely to cherish those concepts."[75]

- On September 8, 2004, Redwood City, California dedicated the courtroom of its renovated historical courthouse (now a museum) to O'Connor.[76]

- In 2004, O'Connor received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[77]

- For her commitment to the ideals of "Duty, Honor, Country", she was awarded the Sylvanus Thayer Award by the United States Military Academy in 2005, becoming only the third woman to receive the award.

- On January 2, 2006, she served as Grand Marshal at the 117th annual Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena, California. She started the 92nd annual Rose Bowl Game with a coin toss on January 4. Coincidentally, the parade was conducted in heavy rain for the first time since 1955, when the Grand Marshal had been then-Chief Justice Earl Warren.

- On April 5, 2006, Arizona State University renamed its law school the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law.[78]

- Yale University awarded O'Connor an honorary doctoral degree at its 305th commencement on May 22, 2006.

- On September 19, 2006, she delivered the Dedication Address for the Elon University School of Law in Greensboro, North Carolina and accepted an Honorary Doctor of Laws degree. Earlier that day, she delivered the Fall Convocation Address at Elon University, where she accepted a Doctor of Laws degree.

- 2007 – Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences[79]

- On March 26, 2008, O'Connor was given the Harry F. Byrd Jr. '35 Public Service Award from the Virginia Military Institute.

- On September 22, 2008, she received the 2008 Franklin Award for commitment to public service and strengthening civic participation from the National Conference on Citizenship.

- On October 7, 2008, she was inducted into the Texas Women's Hall of Fame in Denton, Texas.

- In 2009, Sandra Day O’Connor's house was relocated from its original site on Denton Lane in Paradise Valley to 1230 North College Avenue in Tempe Papago Park. The Wright and Ranch architectural style house was built in 1959. It is considered eligible for landmark designation and listing in the Tempe Historic Property Register by the Historic Preservation Office.[80]

- On April 9, 2009, Sandra Day O'Connor was named Fifteenth Hendrick Fellow by the United States Coast Guard Academy.

- O'Connor was awarded the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama on August 12, 2009.[81][82]

- In October 2011, Sandra Day O'Connor received the Brigham-Kanner Property Rights Prize during the Eighth Annual Brigham–Kanner Property Rights Conference, held at Tsingua University, Beijing, China

- Inducted into San Mateo County Women's Hall of Fame on 21 March 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered