The One That Got Away: The Bittersweet Story of George Orwell and His Childhood Sweetheart

by Maria Popova

“It took me literally years to realise that we are all imperfect creatures but that Eric was less imperfect than anyone else I ever met.”

One summer day in a1914, an English family found a neighborhood boy standing on his head in their garden. When asked about his peculiar position, he replied: “You are noticed more if you stand on your head than if you are the right way up.”

One summer day in a1914, an English family found a neighborhood boy standing on his head in their garden. When asked about his peculiar position, he replied: “You are noticed more if you stand on your head than if you are the right way up.”

The boy was eleven-year-old Eric Blaire, better known today as George Orwell (June 25, 1903–January 21, 1950), and the neighboring family were the Buddicoms, whose three children — Jacintha, Prosper, and Guinever — became young Eric’s favorite playmates. But it was the budding poet Jacintha, two years older than Eric, who captured his heart — soon, between them blossomed the tender and unspoken romantic affection of early adolescence.

And then something happened that abruptly ruptured the relationship — something that would remain a secret for decades, until years after Jacintha’s death in 1994 and more than half a century after Orwell’s.

In the 2006 postscript to Buddicom’s 1974 memoir Eric & Us (public library), her cousin Dione Venables — who was left the copyrights to the book after Buddicom’s death and did significant research in the family archives — tells a disquieting story: Although Eric was a romantically awkward youth reticent to assert himself and unprone to aggression — and although he would grow up to be quite the feminist — during a summer holiday with the Buddicoms shortly before his departure to Burma in 1922, he “attempted to take things further and make SERIOUS love to Jacintha” despite her protestations. Failing to honor the basic “no means no” tenet of respectful intimate relationships, he pinned her down — he was 6’4″ and she just under 5′ — and, despite her exhorting him to stop, managed to rip her skirt and bruise her shoulder. He came to what little was left of his senses before the bodily assault went any further, but the assault on the relationship had fully ruptured it. Eric stayed with the family for the remainder of the holiday, but was kept apart from Jacintha.

Upon returning from Burma five years later, he immediately sought out the Buddicoms, hoping to see Jacintha. Although he could barely make ends meet, he had brought with him an engagement ring for her.

He was invited for a visit, but only her siblings were there and the family was evasive about her absence — an absence shrouded in shame, for it was due to what was considered a grave transgression: Jacintha had just given birth to a child out of wedlock, by a man who fled the country as soon as he found out about the pregnancy. Her aunt and uncle adopted the baby, and she never told Orwell any of what was going on despite their occasional correspondence. He, instead, assumed that Jacintha was gone because she was still hurt and angry with him — which was undoubtedly true, but far from the complete story.

He eventually convinced Prosper to share her London number and telephoned her right away, begging her to meet him so he could make amends. She refused. He tried again two weeks later, but she would not relent. They went their separate ways. Jacintha eventually became the inspiration for many of Orwell’s female characters, most notably Julia in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

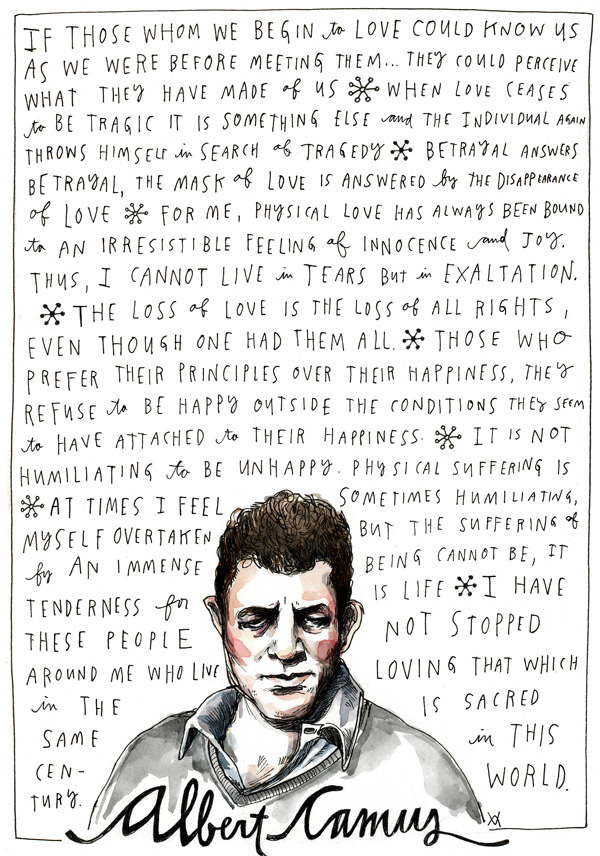

Illustration by Jonathan Burton for a Folio Society edition of 'Nineteen Eighy-Four.' Click image for more.

But the story doesn’t end there. Mere months before Orwell’s death, Buddicom found out in a letter from her aunt that her childhood friend Eric was the famous author George Orwell. Her feelings for him had remained conflicted and complex — she was hurt by his inexplicable youthful outburst, but had also never forgiven herself for not forgiving his flawed humanity and giving him a second change. She was haunted by the latent realization that he had been her big love, the one that got away.

But the story doesn’t end there. Mere months before Orwell’s death, Buddicom found out in a letter from her aunt that her childhood friend Eric was the famous author George Orwell. Her feelings for him had remained conflicted and complex — she was hurt by his inexplicable youthful outburst, but had also never forgiven herself for not forgiving his flawed humanity and giving him a second change. She was haunted by the latent realization that he had been her big love, the one that got away.

In a moving 1972 letter, found in the altogether revelatory George Orwell: A Life in Letters(public library), Buddicom exorcised this conflictedness while trying to console a relative navigating a similar situation of bearing a child out of wedlock. She writes:

I have just finished reading your sad letter and hasten to answer it. I cannot believe that the same miserable tragedy has struck twice in the same family but I CAN give you my total understanding and sympathy which might help a little. Strangely, your letter comes at a time when my mind and concentration are centred on similar events that took place in my life also some time ago.[…]How I wish I had been ready for betrothal when Eric asked me to marry him on his return from Burma. He had ruined what had been such a close and fulfilling relationship since childhood by trying to take us the whole way before I was anywhere near ready for that. It took me literally years to realise that we are all imperfect creatures but that Eric was less imperfect than anyone else I ever met. When the time came and I was ready for the next step it was with the wrong man and the result haunts me to this day… Memories of the joys and fun that Eric and I shared, knowing each others’ minds so totally ensured that I would never marry unless that “oneness”” could be found again.

One can’t help but feel that Buddicom is speaking to her own younger self — this, after all, might be true of most advice ever given — as she issues an unambiguous admonition to the young woman from this ambivalent place of resentment and wistful what-ifs:

You are still an extremely beautiful woman, even if you feel that this has been your downfall. The men in your life have not wanted your very great intelligence and so it has caused you to drift from relationship to relationship, looking for something you never find. A tragedy which you simply must take control of, or life will begin to depend on the bottle rather than the fascination of other lives and situations. At least you have not had the public shame of being destroyed in a classic book as Eric did to me. Julia in Nineteen Eighty-Four is clearly Jacintha, of that I feel certain. He describes her with thick dark hair, being very active, hating politics — and their meeting place was a dell full of bluebells. We always wandered off to our special place when we were at Ticklerton which was full of bluebells. They die so quickly if you pick them so we never did but lay amongst them and adored their heavy pungent scent. That very bluebell dell is described in his book and is part of the central story but in the end he absolutely destroys me, like a man in hob nailed boots stamping on a spider. It hurt my mother so much when she read that book that we always thought it brought on her final heart attack a few days later. Be glad that you have not been torn limb from limb in public.Gather yourself together, my Dear. Our family is well blessed with looks and brains and you have both in liberal quantities. You are an extremely elegant communicator so enjoy what you have instead of looking at the past… You have the finest of minds which outstrips your physical attributes. Make both work for you. Look ahead. What is past is gone. It is the only way I manage to keep my reason.

But the story of Jacintha and Eric isn’t entirely heartbreaking — it has, in fact, a rather bittersweet ending.

In early 1949, as soon as Buddicom found out from her aunt that George Orwell was her childhood friend Eric, she telephoned his publisher to find out where he lived, hoping to reconnect and repair the relationship. Orwell, already in poor health, was being cared for in a sanatorium. She wrote to him on February 9, as soon as she got his address, but dated the letter February 14 — Valentine’s Day.

Orwell was greatly delighted by her missive and responded the very same day, but at first kept his tone rather reserved and signed with the somewhat distancing “Yours, Eric Blair.” He wrote:

I am a widower. My wife died suddenly four years ago, leaving me with a little (adopted) son who was then not quite a year old… I have been having this dreary disease (T.B.) in an acute way since the autumn of 1947, but of course it has been hanging over me all my life, and actually I think I had my first go of it in early childhood… I am trying now not to do any work at all, and shan’t start any for another month or two. All I do is read and do crossword puzzles. I am well looked after here and can keep quiet and warm and not worry about anything, which is about the only treatment that is any good in my opinion. Thank goodness Richard is extremely tough and healthy and is unlikely, I should think, ever to get this disease.

But seeing that the letter wasn’t posted immediately, he wrote a second, far warmer and more emotional one the next day, opening with their favorite childhood greeting:

Hail and Fare Well, my dear Jacintha,… Ever since I got your letter I’ve been remembering. I can’t stop thinking about the young days with you & Guin & Prosper, & things put out of mind for 20 and 30 years. I am so wanting to see you. We must meet when I get out of this place, but the doctor says I’ll have to stay another 3 or 4 months.

What he writes next is of particular poignancy in light of the past — after Jacintha’s illegitimate daughter was born, her sister Guinever had remarked that young Eric “might well have welcomed the little girl as his own child.” Now, thirty years later, in telling Jacintha about his five-year-old adopted son, he poses a question perfectly innocent for him and perfectly piercing for her:

I would like you to see Richard… When I was not much more than his age I always knew I wanted to write, but for the first ten years it was very hard to make a living…Are you fond of children? I think you must be. You were such a tender-hearted girl, always full of pity for the creatures we others shot & killed. But you were not so tender-hearted to me when you abandoned me to Burma with all hope denied. We are older now, & with this wretched illness the years will have taken more of a toll of me than of you. But I am well cared-for here & feel much better than I did when I got here last month. As soon as I can get back to London I do so want to meet you again. As we always ended so that there should be no ending.Farewell and Hail.Eric

Despite their mutual eagerness to reconnect, there was indeed no ending — Orwell’s health suffered a rapid decline over the next few months and he died of a massive lung hemorrhage in the early hours of January 21, 1950. But in this bittersweet epistolary reconciliation, the two shared a grace that few ruptured relationships enjoy — a special kind of closure in that one final, redemptive “Farewell and Hail.”

George Orwell: A Life in Letters is a. Complement these with the beloved author on why he writes, his eleven golden rules for the perfect cup of tea, and some beautifully haunting illustrations for the celebrated novel into which he wrote Jacintha.

Donating = Loving

Bringing you (ad-free) Brain Pickings takes hundreds of hours each month. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider becoming a Supporting Member with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner.

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.

Brain Pickings has a free weekly newsletter. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week’s best articles. Here’s what to expect. Like? Sign up.newsletter

Brain Pickings has a free weekly interestingness digest. It comes out on Sundays and offers the week's best articles. Here's an example. Like? Sign up.

donating = loving

Brain Pickings remains free (and ad-free) and takes me hundreds of hours a month to research and write, and thousands of dollars to sustain. If you find any joy and value in what I do, please consider becoming a Member and supporting with a recurring monthly donationof your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner:

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount:

labors of love

explore

- activism

- advertising

- animation

- art

- books

- children's books

- collaboration

- creativity

- culture

- data visualization

- design

- diaries

- documentary

- education

- film

- happiness

- history

- illustration

- innovation

- interview

- knowledge

- letters

- literature

- love

- music

- omnibus

- out of print

- philosophy

- photography

- poetry

- politics

- psychology

- religion

- remix

- science

- social web

- SoundCloud

- sustainability

- technology

- TED

- video

- vintage

- vintage children's books

- world

- writing

Brain Pickings participates in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to Amazon. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book on Amazon from a link on here, I get a small percentage of its price. That helps support Brain Pickings by offsetting a fraction of what it takes to maintain the site, and is very much appreciated.

Design by: Josh Boston

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered