Prohibition in the United States

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the introduction of alcohol prohibition and its subsequent enforcement in law was a hotly-debated issue. Prohibition supporters, called drys, presented it as a victory for public morals and health. Anti-prohibitionists, known as wets, criticized the alcohol ban as an intrusion of mainly rural Protestant ideals on a central aspect of urban, immigrant, and Catholic life. When federal prohibition legislation was passed, effective enforcement of the ban during the Prohibition Era proved difficult and the law was widely flouted. Without a solid popular consensus for its enforcement, Prohibition led to some unintended consequences and its ultimate repeal in 1933: the growth of criminal organizations, including the modern American Mafia and various other criminal groups, disregard of federal law, and corruption among some politicians and within law enforcement. Despite these criticisms, overall consumption of alcohol halved during the 1920s and remained below pre-Prohibition levels until the 1940s.[2]

Contents

History

The U.S. Senate proposed the Eighteenth Amendment on December 18, 1917. Having been approved by thirty-six states, the amendment was ratified on January 16, 1919, and the country went dry on January 17, 1920.[3][4]On November 18, 1918, prior to ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment, the U.S. Congress passed the temporary Wartime Prohibition Act, which banned the sale of alcoholic beverages having an alcohol content of greater than 2.75 percent.[5] (This act, which was intended to save grain for the war effort, was passed after the armistice ending World War I was signed on November 11, 1918.) The Wartime Prohibition Act took effect June 30, 1919, with July 1, 1919, becoming known as the "Thirsty-First".[6][7]

On October 28, 1919, Congress passed the Volstead Act, the popular name for the National Prohibition Act, over President Woodrow Wilson's veto. The act established the legal definition of intoxicating liquors as well as penalties for producing them.[8] Although the Volstead Act prohibited the sale of alcohol, the federal government lacked resources to enforce it. By 1925, in New York City alone, there were anywhere from 30,000 to 100,000 speakeasy clubs.[9]

While Prohibition was successful in reducing the amount of liquor consumed, it stimulated the proliferation of rampant underground, organized and widespread criminal activity.[10] Many were astonished and disenchanted with the rise of spectacular gangland crimes (such as Chicago's Saint Valentine's Day Massacre), when prohibition was supposed to reduce crime. Prohibition lost its advocates one by one, while the wet opposition talked of personal liberty, new tax revenues from legal beer and liquor, and the scourge of organized crime.[11]

On March 22, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law the Cullen–Harrison Act, legalizing beer with an alcohol content of 3.2 percent (by weight) and wine of a similarly low alcohol content. On December 5, 1933, ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment repealed the Eighteenth Amendment. However, United States federal law still prohibits the manufacture of distilled spirits without meeting numerous licensing requirements that make it impractical to produce spirits for personal beverage use.[12]

Origins

The Drunkard's Progress: A lithograph by Nathaniel Currier supporting the temperance movement, January 1846

In general, informal social controls in the home and community helped maintain the expectation that the abuse of alcohol was unacceptable. "Drunkenness was condemned and punished, but only as an abuse of a God-given gift. Drink itself was not looked upon as culpable, any more than food deserved blame for the sin of gluttony. Excess was a personal indiscretion."[14] When informal controls failed, there were legal options.

Shortly after the United States obtained independence, the Whiskey Rebellion took place in western Pennsylvania in protest of government-imposed taxes on whiskey. Although the taxes were primarily levied to help pay down the newly formed national debt, it also received support from some social reformers, who hoped a "sin tax" would raise public awareness about the harmful effects of alcohol.[15] The whiskey tax was repealed after Thomas Jefferson's Republican Party, which opposed the Federalist Party of Alexander Hamilton and George Washington, came to power in 1800.[16]

Benjamin Rush, one of the foremost physicians of the late eighteenth century, believed in moderation rather than prohibition. In his treatise, "The Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits upon the Human Body and Mind" (1784), Rush argued that the excessive use of alcohol was injurious to physical and psychological health, labeling drunkenness as a disease.[17] Apparently influenced by Rush's widely discussed belief, about 200 farmers in a Connecticut community formed a temperance association in 1789. Similar associations were formed in Virginia in 1800 and New York in 1808.[18] Within a decade other temperance groups had formed in eight states, some of them as being statewide organizations. The words of Rush and other early temperance reformers served to dichotomize the use of alcohol for men and women. While men enjoyed drinking and often considered it vital to their health, women who began to embrace the ideology of 'true motherhood' refrained from consumption of alcohol. Middle-class women, who were considered the moral authorities of their households, consequently rejected the drinking of alcohol, which they believed to be a threat to the home.[18] In 1830, on average, Americans consumed 1.7 bottles of hard liquor per week, three times the amount consumed in 2010.[10]

Development of the prohibition movement

Main articles: Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and Volstead Act

"Who does not love wine, wife and song, will be a fool for his lifelong!" — a vigorous 1873 assertion of the cultural values of German-Americans.

The prohibition movement, also known as the dry crusade, continued in the 1840s, spearheaded by pietistic religious denominations, especially the Methodists. The late nineteenth century saw the temperance movement broaden its focus from abstinence to include all behavior and institutions related to alcohol consumption. Preachers such as Reverend Mark A. Matthews linked liquor-dispensing saloons with prostitution.

Some successes were achieved in the 1850s, including the Maine law, adopted in 1851, which banned the manufacture and sale of liquor. However, it was repealed in 1856. The temperance movement lost strength and was marginalized during the American Civil War (1861–1865).

|

Prohibition era song recorded by Thomas Edison studio, 1922. Duration 3:29.

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

In 1881 Kansas became the first state to outlaw alcoholic beverages in its Constitution. Carrie Nation gained notoriety for enforcing the state's ban on alcohol consumption by walking into saloons, scolding customers, and using her hatchet to destroy bottles of liquor. Nation recruited ladies into the Carrie Nation Prohibition Group, which she also led. While Nation's vigilante techniques were rare, other activists enforced the dry cause by entering saloons, singing, praying, and urging saloonkeepers to stop selling alcohol.[23] Other dry states, especially those in the South, enacted prohibition legislation, as did individual counties within a state.

Court cases also debated the subject of prohibition. Although there was a tendency to support prohibition, some cases ruled in opposition. In Mugler v. Kansas (1887), Justice Harlan commented: "We cannot shut out of view the fact, within the knowledge of all, that the public health, the public morals, and the public safety, may be endangered by the general use of intoxicating drinks; nor the fact established by statistics accessible to every one, that the idleness, disorder, pauperism and crime existing in the country, are, in some degree... traceable to this evil."[24] In support of prohibition, Crowley v. Christensen (1890), remarked: "The statistics of every state show a greater amount of crime and misery attributable to the use of ardent spirits obtained at these retail liquor saloons than to any other source."[24]

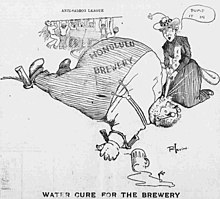

Proliferation of neighborhood saloons in the post-Civil War era became a phenomenon of an increasingly industrialized, urban workforce. Workingmen's bars were popular social gathering places from the workplace and home life. The brewing industry was actively involved in establishing saloons as a lucrative consumer base in their business chain. Saloons were more often than not linked to a specific brewery, where the saloonkeeper‘s operation was financed by a brewer and contractually obligated to sell the brewer’s product to the exclusion of competing brands. A saloon's business model often included the concept of the free lunch, where the bill of fare commonly consisting of heavily-salted food meant to induce thirst and the purchase of drink.[25] During the Progressive Era (1890–1920), hostility toward saloons and their political influence became widespread, with the Anti-Saloon League superseding the Prohibition Party and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union as the most influential advocate of prohibition, after these latter two groups expanded their efforts to support other social reform issues, such as women's suffrage, onto their prohibition platform.

Prohibition was an important force in state and local politics from the 1840s through the 1930s. The political forces involved were ethnoreligious in character, as demonstrated by numerous historical studies.[26] Prohibition was supported by the drys, primarily pietistic Protestant denominations that included Methodists, Northern Baptists, Southern Baptists, New School Presbyterians, Disciples of Christ, Congregationalists, Quakers, and Scandinavian Lutherans. These religious groups identified saloons as politically corrupt and drinking as a personal sin. Other active organizations included the Women's Church Federation, the Women's Temperance Crusade, and the Department of Scientific Temperance Instruction. They were opposed by the wets, primarily liturgical Protestants (Episcopalians and German Lutherans) and Roman Catholics, who denounced the idea that the government should define morality.[27] Even in the wet stronghold of New York City there was an active prohibition movement, led by Norwegian church groups and African-American labor activists who believed that prohibition would benefit workers, especially African Americans. Tea merchants and soda fountain manufacturers generally supported prohibition, believing a ban on alcohol would increase sales of their products.[28] A particularly effective operator on the political front was Wayne Wheeler of the Anti-Saloon League, who made Prohibition a wedge issue and succeeded in getting many pro-prohibition candidates elected. Wheeler became known as the "dry boss" because of his influence and power.[29]

Prohibition represented a conflict between urban and rural values emerging in the United States. Given the mass influx of immigrants to the urban centers of the United States, many individuals within the prohibition movement associated the crime and morally-corrupt behavior of American cities with their large, immigrant populations. Saloons frequented by immigrants in these cities were often frequented by politicians desiring to "buy" immigrants votes in exchange for favors such as job offers, legal assistance, financial help, and trade union memberships. Thus, saloons were seen as a breeding ground for political corruption.[30] In a backlash to the emerging reality of a changing American demographic, many prohibitionists subscribed to the doctrine of nativism, in which they endorsed the notion that America was made great as a result of its white Anglo-Saxon ancestry. This belief fostered resentiments towards urban immigrant communities who typically argued in favor of abolishing prohibition.[31] Additionally, nativist sentiments were part of a larger process of Americanization taking place during the same time period.[32]

Two other amendments to the Constitution were championed by dry crusaders to help their cause. The Sixteenth Amendment (1913), which replaced alcohol taxes that funded the federal government with a federal income tax.[33] Also, since women tended to support prohibition, temperance organizations supported woman suffrage, which was granted after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.[33]

In the presidential election of 1916, the Democratic incumbent, Woodrow Wilson, and the Republican candidate, Charles Evans Hughes, ignored the prohibition issue, as did both parties' political platforms. Democrats and Republicans had strong wet and dry factions, and the election was expected to be close, with neither candidate wanting to alienate any part of his political base.

In January 1917, the 65th Congress convened, in which the dries outnumbered the wets by 140 to 64 in the Democratic Party and 138 to 62 among Republicans. With America's declaration of war against Germany in April, German Americans, a major force against prohibition, were sidelined and their protests subsequently ignored. In addition, a new justification for prohibition arose: prohibiting the production of alcoholic beverages would allow more resources—especially grain that would otherwise be used to make alcohol—to be devoted to the war effort. While wartime prohibition was a spark for the movement,[34] World War I ended before nationwide Prohibition was enacted.

The Defender Of The 18th Amendment. From Klansmen: Guardians of Liberty published by the Pillar of Fire Church

Start of national prohibition (January 1920)

Prohibition began on January 17, 1920, when the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect. A total of 1,520 Federal Prohibition agents (police) were given the task of enforcing the law.Although it was highly controversial, Prohibition received support among diverse groups. Progressives believed Prohibition would improve society as generally did women, southerners, those living in rural areas, and African Americans; however, a few exceptions, such as the Woman’s Organization for Prohibition Reform, opposed it. American humorist Will Rogers joked about southern prohibitionists: "The South is dry and will vote dry. That is, everybody sober enough to stagger to the polls."[citation needed] Supporters of the Amendment soon became confident that it would not be repealed. One of its creators, Senator Morris Sheppard, joked that "there is as much chance of repealing the Eighteenth Amendment as there is for a humming-bird to fly to the planet Mars with the Washington Monument tied to its tail."[37]

At the same time, songs emerged decrying the act. After Edward, Prince of Wales, returned to the United Kingdom following his tour of Canada in 1919, he recounted to his father, King George V, a ditty he had heard at a border town:

| “ |

Four and twenty Yankees, feeling very dry, Went across the border to get a drink of rye. When the rye was opened, the Yanks began to sing, "God bless America, but God save the King!"[38] |

” |

While the manufacture, importation, sale, and transport of alcohol was illegal in the United States, Section 29 of the Volstead Act allowed of wine and cider to be made from fruit at home, but not beer. Up to 200 gallons of wine and cider per year could be made, and some vineyards grew grapes for home use. The Act did not prohibit consumption of alcohol. Many people stockpiled wines and liquors for their personal use in the latter part of 1919 before sales of alcoholic beverages became illegal in January 1920.

Prohibition in the United States did not apply in neighboring countries, where alcoholic drinks were not illegal. Distilleries and breweries in Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean flourished as their products were either consumed by visiting Americans or smuggled into the United States illegally. The Detroit River, which forms part of the U.S. border with Canada, was notoriously difficult to control, especially rum-running in Windsor, Canada. When the U.S. government complained to the British that American law was being undermined by officials in Nassau, Bahamas, the head of the British Colonial Office refused to intervene.[40] Winston Churchill believed that Prohibition was "an affront to the whole history of mankind".[41]

During the time known as the "Roaring Twenties", Chicago became a haven for Prohibition dodgers. Many of Chicago's most notorious gangsters, including Al Capone and his enemy Bugs Moran, made millions of dollars through illegal alcohol sales. By the end of the decade Capone controlled 10,000 speakeasies in Chicago and ruled the bootlegging business from Canada to Florida. Numerous other crimes, including theft and murder, were directly linked to criminal activities in Chicago and elsewhere in violation of Prohibition.[citation needed]

Three federal agencies were assigned the task of enforcing the Volstead Act: the U.S. Coast Guard Office of Law Enforcement,[42][43] the U.S. Treasury Department's IRS Bureau of Prohibition,[44][45] and the U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Prohibition.[46][47]

A policeman with wrecked automobile and confiscated moonshine, 1922

Unpopularity of prohibition and repeal movement

Main article: Repeal of Prohibition

As early as 1925, journalist H. L. Mencken believed that Prohibition was not working.[48]

As the prohibition years continued, more of the country’s populace came

to see prohibition as illustrative of class distinctions, a law

unfairly biased in its administration favoring social elites.

"Prohibition worked best when directed at its primary target: the

working-class poor."[49]

Historian Lizabeth Cohen writes: "A rich family could have a

cellar-full of liquor, but if a poor family had a bottle of home-brew,

there would be trouble.”[citation needed]

Working-class people were inflamed by the fact that their employers

could dip into a cache of private stock while they, the employees, were

denied a similar indulgence.[50]Before the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect in January 1920, many of the upper classes stockpiled alcohol for home consumption. They bought the inventories of liquor retailers and wholesalers, emptying out their warehouses, saloons, and club storerooms. American lawmakers followed these practices at the highest levels of government. President Woodrow Wilson moved his own supply of alcoholic beverages to his Washington residence after his term of office ended. His successor, Warren G. Harding, relocated his own large supply into the White House after inauguration.[51][52]

In October 1930, just two weeks before the congressional midterm elections, bootlegger George Cassiday, "the man in the green hat," came forward and told how he had bootlegged for ten years for members of Congress. One of the few bootleggers ever to tell his story, Cassiday wrote five, front-page articles for The Washington Post. He estimated that eighty percent of congressmen and senators drank, even though they were the ones passing dry laws. This had a significant impact on the midterm election, which saw Congress shift from a dry Republican majority to a wet Democratic majority, who understood that Prohibition was unpopular and called for its repeal.[53] As Prohibition became increasingly unpopular, especially in urban areas, its repeal was eagerly anticipated. Economic urgency played no small part in accelerating the advocacy for repeal. Prior to 1920 the implementation of the Volstead Act, approximately fourteen percent of federal, state, and local tax revenues were derived from alcohol commerce. The government needed this income and also felt that reinstating the manufacture and sale of alcohol would create desperately-needed jobs for the unemployed.[54]

On March 22, 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt signed an amendment to the Volstead Act, known as the Cullen–Harrison Act, allowing the manufacture and sale of 3.2 beer (3.2 percent alcohol by weight, approximately 4 percent alcohol by volume) and light wines. The Volstead Act previously defined an intoxicating beverage as one with greater than 0.5 percent alcohol.[8] Upon signing the Cullen–Harrison Act, Roosevelt made his famous remark: "I think this would be a good time for a beer."[55] The Cullen-Harrison Act became law on April 7, 1933, and the following day Anheuser-Busch sent a team of Clydesdale horses to deliver a case of Budweiser beer to the White House.[citation needed]

Repeal

The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed on December 5, 1933, with ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Despite the efforts of Heber J. Grant, president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a Utah convention helped ratify the Twenty-first Amendment.[56] While Utah can be considered the deciding thirty-sixth state to ratify the Amendment and make it law, both Pennsylvania and Ohio approved it the same day that Utah did.[citation needed]One of the main reasons why enforcement of Prohibition did not proceed smoothly was the inefficient means of enforcing it. From its inception the Eighteenth Amendment lacked legitimacy in the eyes of the public who had previously been drinkers and law-abiding citizens. In some instances the public viewed Prohibition laws as “arbitrary and unnecessary”, and therefore were willing to break them. Law enforcement agents found themselves overwhelmed by the rise in illegal, wide-scale distribution of alcohol due to the Volstead Act. The magnitude of their task was not anticipated and law enforcement agencies lack the resources needed. Additionally, enforcement of the law under the Eighteenth Amendment lacked a centralized authority. Many attempts to impose Prohibition laws were deterred due to the lack of transparency between federal and state authorities. Furthermore, American geography contributed to the difficulties in enforcing Prohibition. The varied terrain of valleys, mountains, lakes, and swamps, as well as the extensive seaways, ports, and borders the United States shared with Canada and Mexico made it exceedingly difficult for Prohibition agents to stop bootleggers given their lack of resources. Ultimately it was recognized with its repeal that the means by which the law was to be enforced was not pragmatic, and in many cases the legislature did not match the general public opinion.[57]

Prohibition was a major blow to the alcoholic beverage industry and its repeal was a step toward the amelioration of one sector of the economy. An example of this is the case of St. Louis, one of the most important alcohol producers before prohibition started, who was ready to resume its position in the industry as soon as possible. Its major brewery had "50,000 barrels" of beer ready for distribution since March 22, 1933, and was the first alcohol producer to resupply the market; others soon followed. After repeal, stores obtained liquor licenses and restocked for business. After beer production resumed, thousands of workers found jobs in the industry again.[58]

Prohibition created a black market that competed with the formal economy, which already was under pressure.[clarification needed] Roosevelt was elected based on the New Deal, which promised economic improvement that was only possible if the formal economy competed successfully against various economic forces, including the black market. This influenced his support for ratifying the Twenty-first amendment, which repealed the Prohibition.[59]

Post-repeal

Additionally, many tribal governments prohibit alcohol on Indian reservations. Federal law also prohibits alcohol on Indian reservations,[62] although this law is currently only enforced when there is a concomitant violation of local tribal liquor laws.[63] The federal law prohibiting alcohol in Indian country pre-dates the Eighteenth Amendment. No constitutional changes were necessary prior to the passage of this amendment, since Indian reservations and U.S. territories have always been considered areas of direct federal jurisdiction.[citation needed]

After repeal of Prohibition, some supporters openly admitted its failure. John D. Rockefeller, Jr. explained his view in a letter written in 1932:[64]

When Prohibition was introduced, I hoped that it would be widely supported by public opinion and the day would soon come when the evil effects of alcohol would be recognized. I have slowly and reluctantly come to believe that this has not been the result. Instead, drinking has generally increased; the speakeasy has replaced the saloon; a vast army of lawbreakers has appeared; many of our best citizens have openly ignored Prohibition; respect for the law has been greatly lessened; and crime has increased to a level never seen before.It is not clear whether Prohibition reduced per-capita consumption of alcohol. Some historians claim that alcohol consumption in the United States did not exceed pre-Prohibition levels until the 1960s;[65] others claim that alcohol consumption reached the pre-Prohibition levels several years after its enactment, and have continued to rise.[66] Cirrhosis of the liver, normally a result of alcoholism, dropped nearly two thirds during Prohibition.[67][68] In the decades after Prohibition, Americans shed any stigma they might have had against alcohol consumption. According to a Gallup Poll survey conducted almost every year since 1939, some two-thirds of American adults age 18 and older drink alcohol.[69]

Prohibition and pietistic Protestantism

Prohibition in the early to mid-twentieth century was fueled by the Protestant denominations in the United States.[70] Pietistic churches in the United States sought to end drinking and the saloon culture during the Third Party System. Liturgical ("high") churches (Catholic, Episcopal, and German Lutheran) opposed prohibition laws because they did not want the government redefining morality to a narrow standard and criminalizing the common liturgical practice of using wine.[71]Revivalism in Second Great Awakening and the Third Great Awakening in the mid- and late-nineteenth century set the stage for the bond between pietistic Protestantism and prohibition in the United States: "The greater prevalence of revival religion within a population, the greater support for the Prohibition parties within that population."[72] Historian Nancy Koester expressed the belief that Prohibition was a “victory for progressives and social gospel activists battling poverty”.[73] Prohibition also united progressives and revivalists.[74]

Effects of Prohibition

Organized crime

Organized crime received a major boost from Prohibition. Mafia groups limited their activities to prostitution, gambling, and theft until 1920, when organized bootlegging emerged in response to Prohibition.[75] A profitable, often violent, black market for alcohol flourished. Powerful criminal organizations corrupted some law enforcement agencies, leading to racketeering.[citation needed] Prohibition provided a financial basis for organized crime to flourish.[76]Rather than reducing crime, Prohibition transformed some cities into battlegrounds between opposing bootlegging gangs.[citation needed] In a study of more than thirty major U.S cities during the Prohibition years of 1920 and 1921, the number of crimes increased by 24 percent. Additionally, theft and burglaries increased by 9 percent, homicides by 12.7 percent, assaults and battery rose by 13 percent, drug addiction by 44.6 percent, and police department costs rose by 11.4 percent. This was largely the result of “black-market violence” and the diversion of law enforcement resources elsewhere. Despite the Prohibition movement's hope that outlawing alcohol would reduce crime, the reality was that the Volstead Act led to higher crime rates than were experienced prior to Prohibition and the establishment of a black market dominated by criminal organizations.[77]

Furthermore, stronger liquor surged in popularity because its potency made it more profitable to smuggle. To prevent bootleggers from using industrial ethyl alcohol to produce illegal beverages, the federal government ordered the poisoning of industrial alcohols. In response, bootleggers hired chemists who successfully renatured the alcohol to make it drinkable. As a response, the Treasury Department required manufacturers to add more deadly poisons, including the particularly deadly methyl alcohol. New York City medical examiners prominently opposed these policies because of the danger to human life. As many as 10,000 people died from drinking denatured alcohol before Prohibition ended.[78] New York City medical examiner Charles Norris believed the government took responsibility for murder when they knew the poison was not deterring people and they continued to poison industrial alcohol (which would be used in drinking alcohol) anyway. Norris remarked: "The government knows it is not stopping drinking by putting poison in alcohol..."[Y]et it continues its poisoning processes, heedless of the fact that people determined to drink are daily absorbing that poison. Knowing this to be true, the United States government must be charged with the moral responsibility for the deaths that poisoned liquor causes, although it cannot be held legally responsible."[78]

Making alcohol at home was very common during Prohibition. Stores sold grape concentrate with warning labels that listed the steps that should be avoided to prevent the juice from fermenting into wine. Some drugstores sold "medical wine" with around a 22 percent alcohol content. In order to justify the sale, the wine was given a medicinal taste.[79] Home-distilled hard liquor was called bathtub gin in northern cities, and moonshine in rural areas of Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia. and Tennessee. Homebrewing good hard liquor was easier than brewing good beer.[79] Since selling privately distilled alcohol was illegal and bypassed government taxation, law enforcement officers relentlessly pursued manufacturers.[80] In response, bootleggers modified their cars and trucks by enhancing the engines and suspensions to make faster vehicles that, they presumed, would improve their chances of outrunning and escaping agents of the Bureau of Prohibition, commonly called "revenue agents" or "revenuers." These cars became known as “moonshine runners” or "'shine runners".[81] Shops were also known to participate in the underground liquor market, by loading their stocks with ingredients for liquors, which anyone could legally purchase (these include: benedictine, vermouth, scotch mash, and even ethyl alcohol).[82]

Prohibition also had an effect on the music industry in the United States, specifically with jazz. Speakeasies became far more popular during that time, and the effects of the Great Depression caused a migration that led to a greater dispersal of jazz music. Movement began from New Orleans and went north through Chicago and to New York. This led to the development of different styles in different cities. Because of its popularity in speakeasies and the development of more advanced recording devices, jazz became very popular very quickly. It was also at the forefront of the minimal integration efforts going on at the time, as it united mostly black musicians with mostly white audiences.[83]

Along with other economic effects, the enactment and enforcement of Prohibition caused an increase in resource costs. During the 1920s the annual budget of the Bureau of Prohibition went from $4.4 million to $13.4 million. Additionally, the U.S. Coast Guard spent an average of $13 million annually on enforcement of prohibition laws.[84] These numbers do not take into account the costs to local and state governments.

When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, organized crime lost nearly all of its black market profits from alcohol in most states, because of competition with legal liquor stores selling alcohol at lower prices. (States still retained the right to enforce their own state laws concerning alcohol consumption.)[citation needed]

Other impacts

Men and women drinking beer at a bar in Raceland, Louisiana,

September 1938. Pre-Prohibition saloons were mostly male

establishments; post-Prohibition bars catered to both males and females.

As the saloon began to die out, public drinking lost much of its macho connotation, resulting in increased social acceptance of women drinking in the semi-public environment of the speakeasies. This new norm established women as a notable new target demographic for alcohol marketeers, who sought to expand their clientele.[85]

In 1930 the Prohibition Commissioner estimated that in 1919, the year before the Volstead Act became law, the average drinking American spent $17 per year on alcoholic beverages. By 1930, because enforcement diminished the supply, spending had increased to $35 per year (there was no inflation in this period). The result was an illegal alcohol beverage industry that made an average of $3 billion per year in illegal untaxed income.[86]

Heavy drinkers and alcoholics were among the most affected groups during Prohibition. Those who were determined to find liquor could still do so, but those who saw their drinking habits as destructive typically had difficulty in finding the help they sought. Self-help societies had withered away along with the alcohol industry. In 1935 a new self-help group was founded: Alcoholics Anonymous (AA).[85]

Prohibition had a notable effect on the alcohol brewing industry in the United States. When Prohibition ended, only half the breweries that previously existed reopened.[citation needed] Wine historians note that Prohibition destroyed what was a fledgling wine industry in the United States. Productive, wine-quality grapevines were replaced by lower-quality vines that grew thicker-skinned grapes, which could be more easily transported. Much of the institutional knowledge was also lost as winemakers either emigrated to other wine producing countries or left the business altogether.[87] Distilled spirits became more popular during Prohibition.[79] Because of its higher alcohol content in comparison to fermented wine and beer, it became common to mix and dilute the hard alcohol.[79]

Winemaking during Prohibition

The Volstead Act specifically allowed individual farmers to make certain wines "on the legal fiction that it was a non-intoxicating fruit-juice for home consumption",[88] and many did so. Enterprising grape farmers produced liquid and semi-solid grape concentrates, often called "wine bricks" or "wine blocks".[89] This demand led California grape growers to increase their land under cultivation by about 700 percent during the first five years of Prohibition. The grape concentrate was sold with a warning: "After dissolving the brick in a gallon of water, do not place the liquid in a jug away in the cupboard for twenty days, because then it would turn into wine."[14] One grape block producer sold nine varieties: Port, Virginia Dare, Muscatel, Angelica, Tokay, Sauterne, Riesling, Claret and Burgundy.[citation needed]The Volstead Act allowed the sale of sacramental wine to priests and ministers, and allowed rabbis to approve sales of sacramental wine to individuals for Sabbath and holiday use at home. The Bureau of Internal Revenue maintained a list of ecumenical organizations that could be used for verifying licensure.[citation needed] Among Jews, four rabbinical groups were approved, which led to some competition for membership, since the supervision of sacramental licenses could be used to secure donations to support a religious institution. There were known abuses in this system, with imposters or unauthorized agents using loopholes to purchase wine.[33][90]

See also

- Cultural and religious foundation

- Controlled substances

- Legal foundation

- Lawbreakers and illegal practices

- Places involved in smuggling

- Law-enforcement organizations

- Similar policies and institutions

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered