Magazine

Drawing what our mouths cannot say

- 12 June 2015

- Magazine

For some, it's easier to communicate with a drawing than it is with talking.

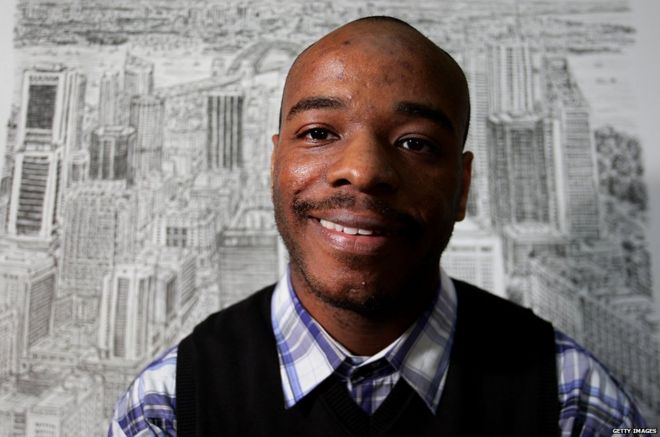

It is a rainy afternoon but people are queuing outside a Mayfair gallery to buy books and prints and get them signed by the artist.

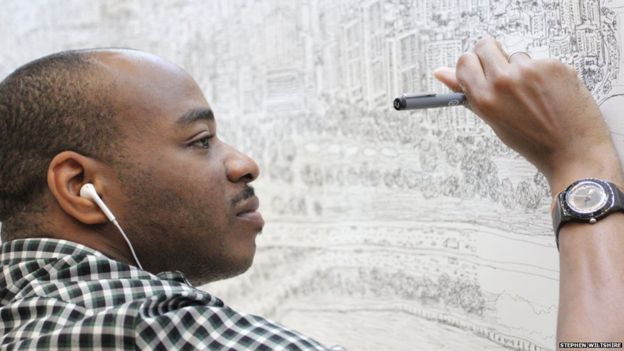

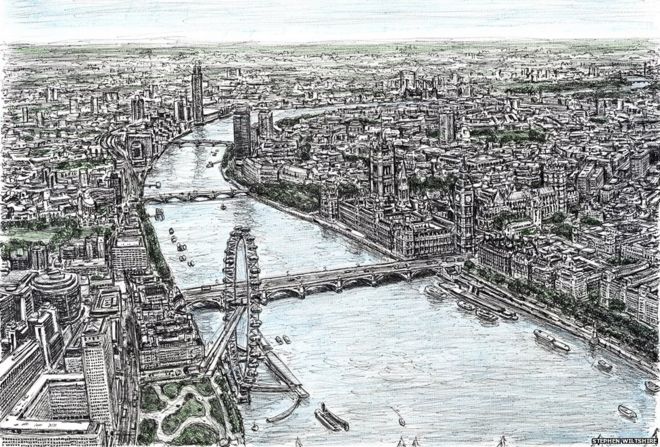

The gallery's owner, Stephen Wiltshire, is world famous for his incredibly detailed pen and ink drawings of buildings and cityscapes.

Sitting at a table inside, he smiles shyly as people shower him with compliments.

"Cities are so beautiful," he says in a soft voice. "The skylines. . . the high rise buildings."

Stephen's speech is slow and hesitant. His sister Annette is by his side to encourage him and to clarify some of the questions he is being asked.

At the age of three, Stephen was diagnosed with autism and Annette says he found all human contact difficult - especially after their father Colvin's death in a motorcycle accident. Stephen didn't speak when he started primary school.

"He was the quiet pupil in the corner of the class - he didn't say anything or interact with anyone," she says. "He just kept his head down scribbling on paper."

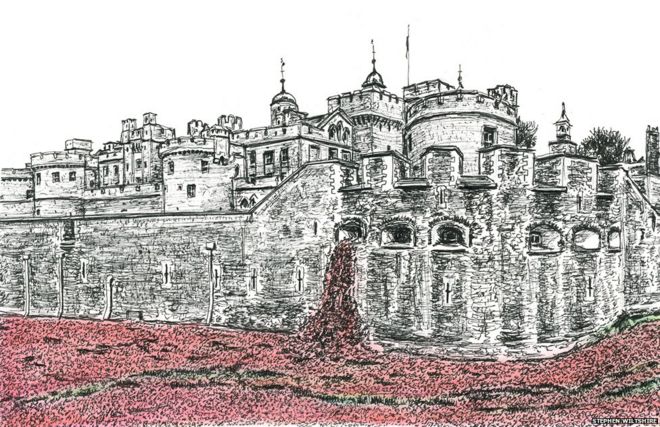

Every week the children were taken to visit landmarks of the capital such as Big Ben and the Tower of London. Back in the classroom they were asked to draw what they had seen. Stephen's teachers quickly realised his work was extraordinarily advanced for his age and that he loved to draw. So they played a trick on him.

"They took away his pen and paper and tried to make him ask for them back," says Annette. "He was so frustrated - he needed them so badly that he was forced to say 'pen' and 'paper '. Those were his first words."

Soon people outside the school started noticing Stephen's gift and aged eight he landed his first commission - a sketch of Salisbury Cathedral for the former Prime Minister Edward Heath.

Stephen went from a silent, withdrawn child to an artist whose time-lapse videos go viral on YouTube and whose works sell for six-figure sums. Cityscapes are his trademark - like a 10m-long panoramic memory drawing of Tokyo produced after a single helicopter ride over the Japanese capital.

That was a decade ago and since then Stephen has produced aerial illustrations of several cities inspired by the "bird's eye view" he gets while flying over a metropolis. The draughtsmanship is assured, the perspective masterful. But how does he manage to capture so much detail from the elaborate cornices of buildings, to shadows cast by the sun to the correct number of windows on a skyscraper? How does he keep all that in his head?

"I make a quick sketch from the air in my sketch pad," he replies with a slight shrug of the shoulders.

"You go back to the hotel don't you?" says Annette. "And then you have the night to memorise what you have sketched and prepare."

Stephen's gift for drawing has long fascinated neurologists and psychologists.

Travelling around the world with her brother, Annette has noticed how his gift evokes strong and unexpected responses in people.

"A crowd of 150,000 came to welcome him in Singapore," she recalls. "When they saw him drawing some were cheering, others were crying. Some turned up at dawn to wait for him and I will never forget this old man who was there every single day. No matter how big the crowd was, he always managed to push his way to the front row to get close to Stephen. I will never forget that old man's face."

Despite his autism, Stephen is a powerful communicator - his eloquence is in his pen.

In some situations drawing is used to express what's too hard to say in words.

Jebet Mengech is an arts manager at Kids Company, a London charity which supports children from disadvantaged backgrounds. She says encouraging boys and girls to express themselves with crayons, pencils and felt tips helps her and her team to identify the most vulnerable children.

"Sometimes drawing is less intimidating than sitting and looking an adult in the eye. Instead they can talk to us while they're focusing on the paper in front of them and the picture becomes a sort of mediator."

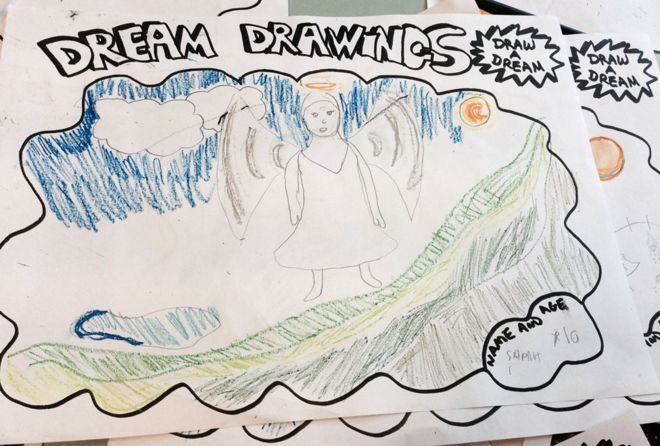

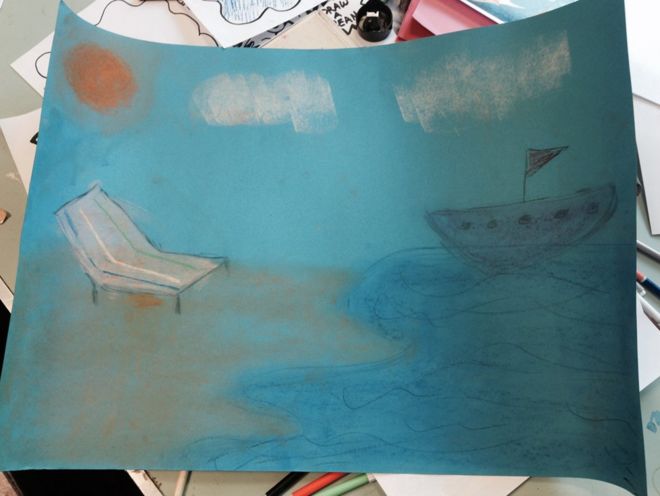

In the art room of the charity's after school centre in Camberwell the atmosphere is noisy and joyous. The theme is drawing your dream and there are pictures of angels, princesses, swimming pools and Mickey Mouse. But one girl, aged nine, has drawn a female figure in a long dress whose mouth is a great, black circle in the middle of her face. Is she a princess? "Yeah. Not a happy princess," the girl says quietly, throwing her pencil down on the table.

Some drawings reflect a child's mood, others contain important information, says Mengech. "When we asked children to draw what they eat at home, we saw many empty plates or tiny portions and it was clear that some kids really weren't getting enough to eat," she says.

It emerged that a boy who had drawn a desert island and palm trees was traumatised after his mother suddenly left the family home to return to her country of origin.

"Until we talked to him about the drawing, no-one was aware that he was dealing with feelings of abandonment," says Mengech. "He drew a suitcase because the last time he saw his mum she was packing and he said he often saw her suitcase in his nightmares."

One in six children "report" things in their artwork which staff at Kids Company see as a cause for concern, Mengech explains. Drawings might reveal everything from a lack of food or homes infested with rodents to children acting as carers for younger siblings to even more serious issues.

"Most often the drawings highlight poverty or cases of neglect," says Mengech, "Children having to survive on their own. But sometimes they point to abuse, incidents of violence and children have reported knives as weapons in the home as well.

"Drawing allows the children to tell stories about what is going on in their lives", she says.

It is not just children who use drawing to broach difficult topics.

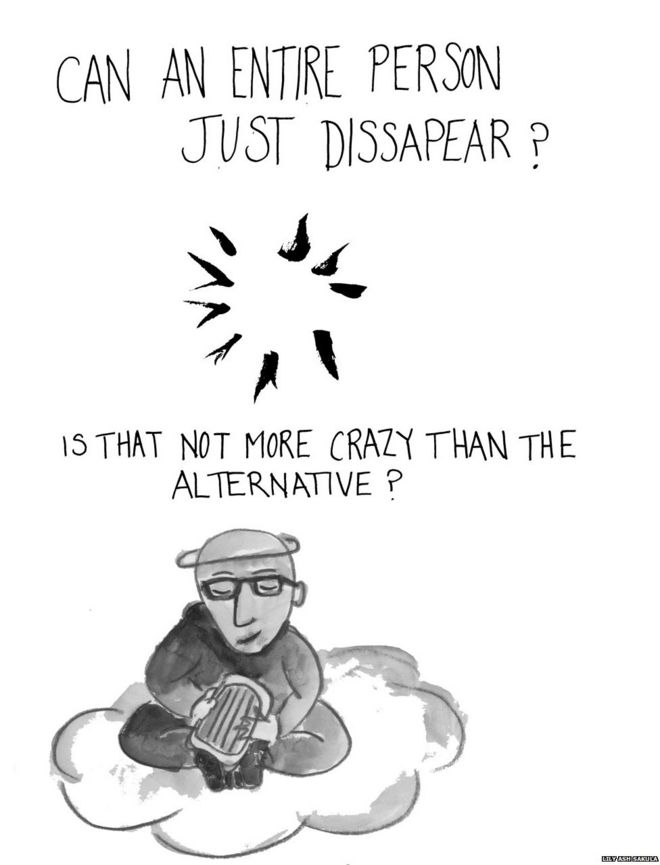

My niece, Lily Ash Sakula, began drawing after her boyfriend Patrick suddenly died from cancer in his mid-20s.

Her grief was so "amorphous and raw" that she felt she couldn't share it with friends or family.

"It was painful to watch other people's faces, a mixture of pain, powerlessness and awkwardness," she says. "It's hard to put people you love through that, so I mostly stopped trying to in conversation."

Instead she reached for her sketchbook. "With drawing there is a space between you and the viewer. You can both process your feelings separately."

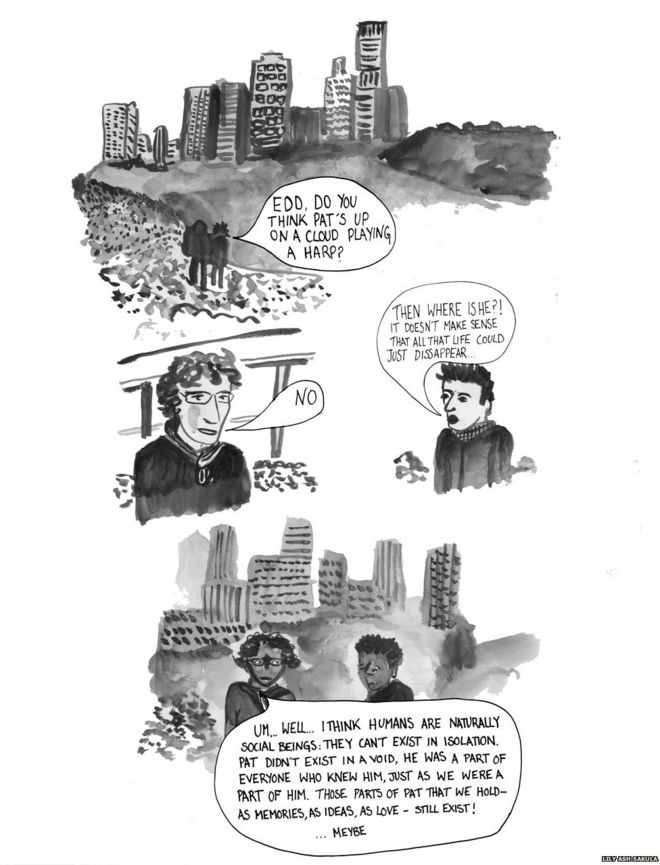

Lily took a break from her job as a social entrepreneur in London and moved to Portland, Oregon, a city which boasts more cartoonists per capita than anywhere in the Western hemisphere.

"I like comics because you are using pictures and words to tell a story but you have to be extremely minimalist with both, so it really forces you to get down to the essence of what you're trying to convey," she says.

She is now working on her first graphic novel which focuses on her relationship with Patrick and her attempts to come to terms with his death.

"The process of drawing Patrick has been really hard. Especially going back over photos to get his face or nose right. But at the same time it is a relief to get these thoughts about him and grief and death down on paper rather than have them endlessly swirling around my head."

The Why Factor is broadcast on BBC World Service on Fridays at 18:30 BST. Listen to the drawing episode via iPlayer or The Why Factor download.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered