Magazine

A Point of View: How time passes differently as you get older

- 5 June 2015

- Magazine

Growing old changes people's perceptions of the past and the future, writes AL Kennedy.

I'm getting old. Not older, just old. There are various ways of confirming this: Checking the crumply inside of my elbows, noticing people on the underground offer me their seats now - which is odd, because as a child I was usually exhausted and desperate to sit down on public transport, but not allowed to, while at present I quite like standing - and recently someone on Twitter called me a "silly old cow". Silly? Yeah, now and then. Cow? Well if you insist. But old?

Actually, I don't mind being old - as the joke goes, consider the alternative - but I do find it's making me think more about those two confusing companions, the future and the past.

When I was an exhausted child, the past was extremely simple. There was history, which was enormous and presented as definitive and - with the exception of the Ancient Egyptians - seemed to have involved very few people who were foreign, or women, or not white. And then there were my memories, which involved a relatively brief catalogue of highly-polarised events. There were horrible memories of failing to be good at arithmetic, or of the boy who liked kicking me in the shin during morning playtimes. And there were great memories - of my Grandad's voice calling me Tiger, or of drinking Creamola Foam.

The future was oddly small, given that I had a lot of it to come at that point. It was basically a blank peppered with islets of clarity, which were either immediately threatening - long division and kicking - or more vaguely nice - the promise of holidays, Grandpop, getting mildly high on red colouring and sugar. And both the past and the future were capable of waking me at 03:00 for self-centred fear or excitement - hence my exhaustion.

Becoming an adult, of course, alters many of our ideas about time. We get used to its relativity - the fact that a migraine seems to last for decades, while fun with a loved one burns away like a half-inch fuse. We perceive our memories differently as we age. I've been told that last year's summer when I was five seemed long as a mission to Mars, because it was such a large proportion of my lived time at that point, while last year's summer today seems to have involved one stroll in the country and planting some strawberries. I'm pretty sure I also wasn't paying that much attention to last summer, because I was busy and summers had happened to me before.

And the wider past and future may alter for us, too. Growing up, which can be literally disenchanting, has meant that I've discovered history isn't static and rarely leaves us. Many of my school history lessons were, in retrospect, bizarrely misleading and limited as school history lessons sometimes are. Travelling abroad and eventually just reading rather more varied history books allowed me to discover that, for example, history happened to foreigners and women, too. The past isn't only white, only British, only flattering to Britain, or even concerned with Britain. Fully appreciating this removed that final remnant of my very young self - a small person who really did insist on standing up during the national anthem, even when alone in my own living room. But it made the world more interesting. By making it less about only me and my concerns. It was a way of learning - in a large sense - that everything is rarely all about me.

In a way, I was simply very slow to learn that history is shaped by continued research. And, of course, it's also shaped by political will. Last year's anniversary of World War One's outbreak and continuing responses to the conflict give us a chance, not only to remember that handful of cataclysmic, world-changing years, but also to witness an ideological tussle between those who feel war is best remembered as the shedding of blood and those who feel it's best represented as an outbreak of flowers. If history were like arithmetic - two plus two always being four - we'd have a chance to keep it simple and definitive, but it's so large, it has so many perspectives. It offers so many opportunities to play with our sense of self and our emotions. Manipulated history can offer us clumsy impostures like Piltdown man, or the vile fantasies involved in Holocaust denial. History as a vital, exacting discipline, can show us how whole populations of normal people can be persuaded to behave horrifically, if they're overwhelmed by histories of past glory, of injustice and suffering at others' hands. Attack is so much easier to sell, if it's packaged as pre-emptive defence. Part of growing up involves realising that nation's futures, good and bad, can leap from their perceptions of the past.

Grumbling about propagandists is easy, but if I look at my own past - especially when I let that be all about me - I'm consistently guilty of propaganda campaigns. If I'm feeling cheerful, the last time I met my gentleman of choice he was pleased to see me, possibly even impressed. Which makes me more cheerful, which makes other memories of him more rosy. If I'm glum, our last encounter dreadful and all is lost. He isn't just there, being himself but in the past tense - he's a tall expression of my convoluted ego.

Which is where those 03:00 alarm calls re-emerge. In adulthood, worry, rather than joyful anticipation has tended to monopolise my sleepless nights. There I lie, clamped under my quilt, while everything I've ever done apparently falls apart and proves that everything I ever will do can fragment even more quickly. I know I'm not alone in this. It's a comforting historical fact that Old English had a special word - uhtceare - for what we just have to call pre-dawn anxiety. And it also reassures me that most directors - and maybe audiences - of Chekhov's play The Three Sisters haven't let the character Vershinin say the line "In two or three hundred years life on this earth will be beautiful beyond our dreams, it will be marvellous" without some show of irony, or idiocy.

Perhaps this is partly because history tells us that 19th Century Russia's hopes for change didn't herald paradise on earth. Then again - Vershinin's prediction still has some time to run and Chekhov doesn't seem to have meant it purely as a joke.

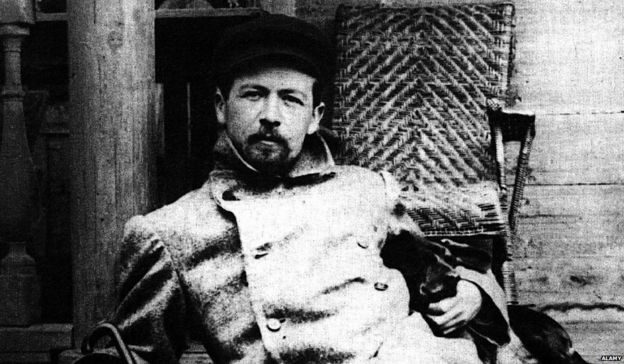

Chekhov wrote about the power of narratives to summon the reader, draw them on. Both the future and the past are narratives. If we look at Anton Pavlovich Chekhov's history, we see a brutalised child, then a man who was prone to depression and who saw the unjust society around him very clearly. We see a doctor who knew he had TB. Nevertheless, he repeatedly chose to act as if he were being summoned by a welcome and inspiring future. He treated the sick, even the penniless sick, organised poor relief, encouraged other writers and wrote to bring unnecessary miseries to light, as well as - he hoped - to move people and make them laugh. One of his brothers, Mikhail, recalled that the nearer he was to death, the less he realised it. Or maybe Chekhov realised it very much and decided to live as if his story had no ending, to be fully in the present.

The present can be an antidote to our more and less fantastic visions of the past and the future. Those Ancient Egyptians I liked so much as a child sometimes painted a sun disc guarded, before and behind, by a lion. There it is - the rising and setting sun, the day, now - held between past and future. In my personal symbology, I take it that even mythical lions dislike being disturbed so, beyond necessary planning, my mind should keep to the present. The trouble is, unless my attention's focussed by an immediate threat, my thoughts slip away, before and behind. Mostly, the best I can do is monitor what stories I tell myself about my past and my future. Because those stories change me and my present - they're like spells. Do I claim everything's worse than it was in my day? People have been doing that for at least 3,000 years. Do I make it all about me - and my fears? Or do I act and work as if I'm building something beautiful beyond our dreams? I think only that last one offers an access to peace. Whatever else, at 03:00, I need to leave those lions alone.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered