SPECIAL REPORT: CRUDE CONSIDERATIONS

Recent derailments have raised questions of safety, method of transporting oil

Pipelines and tank cars both pose benefits and risks

image: http://www.toledoblade.com/image/2015/03/26/300x_b1_cCM_z_cBR/29n1rail-4.jpg

Empty and loaded oil trains pass each other just west of I-75 near downtown Toledo.

Empty and loaded oil trains pass each other just west of I-75 near downtown Toledo.THE BLADE/DAVID PATCHEnlarge | Buy This Photo

President Obama’s veto of the proposed Keystone XL pipeline has major ramifications for North America’s energy future.

But it also has intensified the debate about whether it is safer to transport crude oil via pipelines or railroad tank cars.

Though statistics show pipelines are safer, more efficient at moving product, and, thus, release fewer climate-altering greenhouse gases than an equivalent amount of crude shipped along a more energy-intensive rail system, pros and cons of each mode of transportation are being amplified by lobbyists — especially in the wake of several recent, catastrophic oil-train derailments.

RELATED STORY: Keystone proposal puts focus on sensitive areas

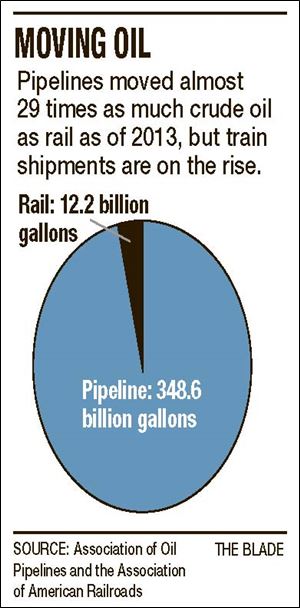

In 2013, America moved 8.3 billion barrels (348.6 billion gallons) of crude oil via pipeline — nearly 29 times the 291 million barrels (12.2 billion gallons) moved by rail, according to figures from the Association of Oil Pipelines and the Association of American Railroads.

A Washington Post analysis showed pipelines average about 22 accidents per billion barrels of oil transported in recent years, while the rate over rail is 10 to 20 times higher.

“A pipeline, whether you’re moving a liquid or natural gas, is always going to be more efficient than rail or for that matter, anything else. It’s the safest way,” said Jimmy Stewart, president of the Ohio Gas Association. He said he thinks of America’s 2.6 million miles of pipelines — a buried web people drive and walk across daily — as arteries supporting the nation’s economic heartbeat.

“It amazes me the rhetoric that comes out of some peoples’ mouths about pipelines when they walk and drive over them every day,” Mr. Stewart said. “It’s insulting, quite honestly.”

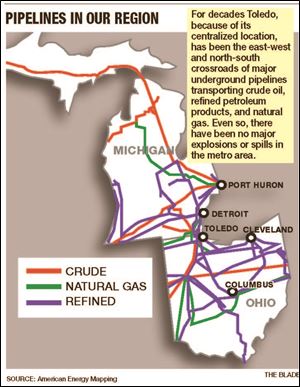

For decades Toledo, northwest Ohio, and southeast Michigan have hosted numerous east-west and north-south major underground pipelines transporting crude oil, refined petroleum products, and natural gas, yet there have been no major explosions or spills.

image: http://www.toledoblade.com/image/2015/03/26/300x_b1_cCM_z_cBR/29n1pipe-3.jpg

Technicians work on an Enbridge pipeline near Fredonia Township, Mich., in August, 2010.

Technicians work on an Enbridge pipeline near Fredonia Township, Mich., in August, 2010.EPAEnlarge

Oil on the move

According to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, part of the U.S. Department of Transportation, it would take about 750 tanker trucks a day, loading up and moving out every two minutes, to move even a modest pipeline’s volume.

“The railroad equivalent of this single pipeline would be a train of 75 2,000-barrel tank rail cars every day,” that agency says.

It’s not just a rash of high-profile train wrecks that have people talking.

Safety experts see North America at a turning point because of the oil and gas industry’s rapid increase in hydraulic fracturing of shale bedrock, a process commonly known as “fracking” that the U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts will remain strong for at least the next 30 years.

Fracking actually has occurred commercially since the 1950s. But the game-changer occurred less than a decade ago, when a technique developed to combine horizontal drilling with fracking made it economical to go after vast reserves of previously trapped oil and natural gas worldwide — including in eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania, where Utica and Marcellus shale regions meet.

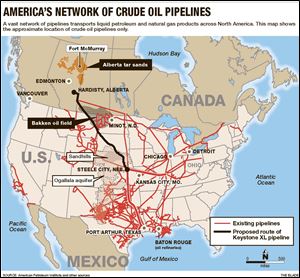

Couple that with huge investments made to refine heavy Alberta oil sands — commonly called “tar sands” — at sites including BP’s Toledo-area refinery in Oregon, and the big-picture debate about Keystone XL has put the country’s energy future at a crossroads.

To many people, the debate about the $8 billion project — which needs a congressional override of Mr. Obama’s veto to move forward — symbolizes the degree to which Americans remain willing to stay hooked on what former President George W. Bush described near the end of his second term seven years ago as the nation’s “heroin-like addiction to oil.”

image: http://www.toledoblade.com/image/2015/03/26/300x_b1_cCM_z_cTR/29n1burn-1.jpg

Derailed oil tanker train cars burn near Mount Carbon, W.Va. A CSX train carrying more than 100 tankers of crude oil derailed in February during a snowstorm, sending a fireball into the sky and threatening the water supply of nearby residents.

Derailed oil tanker train cars burn near Mount Carbon, W.Va. A CSX train carrying more than 100 tankers of crude oil derailed in February during a snowstorm, sending a fireball into the sky and threatening the water supply of nearby residents.(CHARLESTON, W.VA.) DAILY MAILEnlarge

Keystone question

TransCanada’s proposed Keystone XL would deliver 830,000 barrels (34.9 million gallons) a day of heavy petroleum from the oil sands of Alberta and the Bakken fields of North Dakota and Montana to Texas and Louisiana refineries on the Gulf Coast.

According to the U.S. State Department, the pipeline would cross into the United States near Morgan, Mont., and continue through Montana, South Dakota, and Nebraska, where it would connect to existing pipeline facilities near Steele City, Neb., for delivery to Cushing, Okla., and the Gulf Coast.

The State Department said in 2014 that oil extracted from Canadian oil sands produces about 17 percent more climate-altering carbon dioxide than conventionally extracted oil, an estimate think tanks such as the Stockholm Environment Institute claim is way too low.

“I don’t think anyone thinks we’re getting off oil tomorrow. But there’s a big difference between embracing that and embracing the dirtiest form of oil on the planet — and not only embracing it, but doubling down on it,” Josh Mogerman, Natural Resources Defense Council media program deputy director, said of tar-sands oil that would come down Keystone XL. “Building that pipeline sends a market signal.”

Conservative think tanks such as the Chicago-based Heartland Institute fumed over Mr. Obama’s veto.

“In one fell swoop, President Obama killed thousands of American jobs, raised domestic energy prices, and ensured greater U.S. dependence on oil from nations that are openly hostile to freedom, democracy, and the United States of America,” said James M. Taylor, Heartland’s senior fellow for environmental policy.

Environmentalists such as the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Mr. Mogerman oppose Keystone XL because they believe it will create a greater dependency on tar sands and crude oil in general — not whether pipelines can deliver petroleum products with fewer greenhouse gases than by rail.

image: http://www.toledoblade.com/image/2015/03/26/300x_b1_cCM_z_cTL/29n1spill-5.jpg

A worker monitors water in Talmadge Creek in Marshall Township, Michigan, near the Kalamazoo River, in July, 2010. Crews were attempting to contain oil that spilled from a ruptured pipeline.

A worker monitors water in Talmadge Creek in Marshall Township, Michigan, near the Kalamazoo River, in July, 2010. Crews were attempting to contain oil that spilled from a ruptured pipeline.ASSOCIATED PRESSEnlarge

“The Keystone fight is a fight about tar sands,” Mr. Mogerman said. “But really, it’s more about how we deal with oil in the future in this country.”

To Mr. Stewart and other pipeline advocates, killing the Keystone XL pipeline gives environmentalists a false sense of victory because production is so high and demand is so great now that crude oil “is still going to find its way to market by other means.”

“The folks who think they’ve really cracked down have made it worse because that will require more energy to be expended [moving the crude by rail],” he said.

That likewise was the conclusion of a 2014 U.S. Department of State report.

Riding the rails

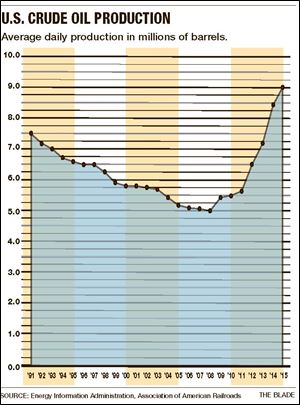

Railroads moved 493,126 tank cars of oil in 2014, a nearly 5,200 percent increase over the 9,500 tank cars that hauled oil before the fracking boom began to hit its stride in many parts of North America in 2008.

Overall domestic crude production has risen 70 percent during that same period. U.S. Energy Information Administration figures show domestic oil produced at a rate of 8.5 million barrels a day in 2014, up from 5 million barrels a day in 2008. This year, crude is expected to be produced at a rate of 9 million barrels a day, just shy of its peak rate of 9.6 million barrels a day in 1970, according to the Energy Information Administration.

“While pipelines transport the majority of oil and gas in the United States, recent development of crude oil in parts of the country underserved by pipeline has led shippers to use other modes, with rail seeing the largest percentage increase,” a Government Accountability Office report said. “Although pipeline operators and railroads have generally good safety records, the increased transportation of these flammable hazardous materials creates the potential for serious accidents.”

image: http://www.toledoblade.com/image/2015/03/29/300x_b1_cCM_z_cTL/n1oilrigs.jpg

Oil rigs pump out crude in the Bakken shale field in western North Dakota.

Oil rigs pump out crude in the Bakken shale field in western North Dakota.ASSOCIATED PRESSEnlarge

The agency cited a need for better U.S. Department of Transportation rules on flammability of products shipped by rail and a greater emphasis on emergency preparedness, “especially in rural areas where there may be fewer resources to respond to a serious incident.”

Trains of 80 to 100 crude oil cars are becoming more common, with each train car carrying about 30,000 gallons of oil.

Canada’s ambassador to the United States, Gary Doer, has warned the Obama Administration several times since 2011 there will be a sharp increase in cross-border train shipments of crude unless Keystone XL is built, a statement echoed by Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

“His choice is to have it come down by a pipeline that he approves, or without his approval, it comes down on trains,” Mr. Doer told the Globe and Mail in the summer of 2013. “That’s just the raw common sense of this thing, and we’ve been saying it for two years and we’ve been proven correct. At the end of the day, it’s trains or pipelines.”

Train incidents

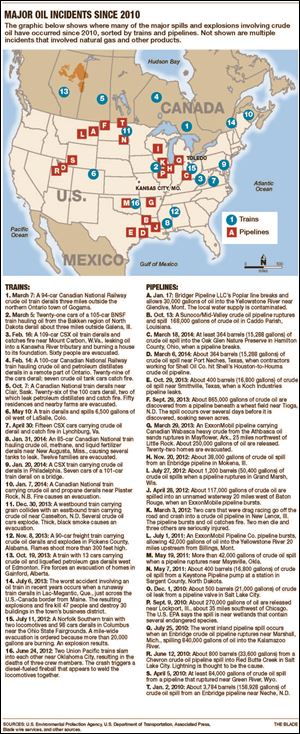

Major incidents involving trains include one March 7, when a 94-car Canadian National Railway crude oil train derailed three miles outside the northern Ontario town of Gogama, and another two days earlier in which 21 cars of a 105-car BNSF Railway train hauling oil from the Bakken region of North Dakota derailed about three miles outside Galena, Ill.

That pair of incidents followed two major derailments in February.

On Feb. 16, part of a 109-car CSX oil train derailed and burned near Mount Carbon, W.Va., leaking oil into a Kanawha River tributary and burning a house to its foundation. On Feb. 14, a 100-car Canadian National train hauling crude oil and petroleum distillates derailed only 23 miles from the March 7 incident scene. Both fires burned for nearly a week, the latter causing explosions.

The worst recent oil-train accident occurred July 6, 2013, when a runaway train derailed in Lac-Megantic, Que., just across the U.S.-Canada border from Maine. The resulting explosions and fire killed 47 people and destroyed the town’s business district.

Such events “get people to think, obviously,” said Michael Barnes, Enbridge operations and project communications senior manager.

“You live with risk,” he said. “Most of the public just takes for granted they have energy to turn on and off. There are no short-term answers.”

Pipeline issues

Though not as often as tanker train derailments, pipelines have ruptured, resulting in huge oil spills, wildlife losses, and contaminated water.

The critical thing with pipelines, safety experts say, is the time it takes for sensors to let operators know to shut off delivery when there’s a problem.

Industry officials say those safety measures and training have improved in recent years for pipelines in general.

Some of the more noteworthy spills involving oil pipelines include one on Jan. 17, when Bridger Pipeline LLC’s Poplar line broke and allowed 30,000 gallons of oil into the Yellowstone River near Glendive, Mont., contaminating the local water supply. Bridger said the pipeline was shut down within an hour of the leak.

On Oct. 13, 2014, a Sunoco/Mid-Valley crude oil pipeline ruptured and spilled 168,000 gallons of crude oil in Caddo Parish, La. A little more than 18 months earlier, on March 29, 2013, an ExxonMobil pipeline carrying Canadian Wabasca heavy crude from the Athbasca oil sands ruptured in Mayflower, Ark., 25 miles northwest of Little Rock. About 250,000 gallons of oil were released and 22 homes were evacuated.

And on July 1, 2011, an ExxonMobil Pipeline Co. pipeline burst, allowing 42,000 gallons of oil into the Yellowstone River 20 miles upstream from Billings, Mont.

America’s largest inland oil spill from a pipeline rupture occurred July 25, 2010, when an Enbridge pipeline ruptured near Marshall, Mich., spilling 840,000 gallons of tar sands crude into a scenic part of the Kalamazoo River and causing more than $767 million in damage.

A multiagency emergency response crew worked feverishly around the clock to keep the oil sludge from entering Lake Michigan and other downstream sources of public drinking water. Dozens of volunteers fought to save whatever wildlife they could.

The National Transportation and Safety Board concluded in the Kalamazoo River case, though, that the problem was exacerbated by Enbridge’s sluggishness. The line break near Marshall was not discovered for more than 17 hours. About 320 people reported symptoms consistent with crude oil exposure, the NTSB said.

Such events have become case studies for those who specialize in the arcane field of risk assessment.

“There’s some measure in risk involved in every single thing you do,” the Ohio Gas Association’s Mr. Stewart said.

Enbridge’s Mr. Barnes agreed.

“Here’s something people don’t want to admit,” he said. “Everything man builds is fallible.”

Many people probably don’t realize they’re far more likely to die being struck by lightning than from a pipeline explosion, according to the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, which concluded in a report that pipelines are the safest mode of transporting oil and natural gas.

David Ropeik, a former Harvard School of Public Health instructor who specialized in risk communication, said human nature is to worry out of proportion to risk when major news events make us “suddenly more aware of it.”

“Even if the likelihoods are low, if one or two out-of-the-ordinary, high-consequence events occur, that will make the risk feel scarier than the numbers say it is,” he said.

Contact Tom Henry at: thenry@theblade.com, 419-724-6079, or via Twitter @ecowriterohio.

Read more at http://www.toledoblade.com/local/2015/03/29/Pipelines-vs-rail-tank-cars.html#kw2lKwjKWvciG8jT.99

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered