Thomas Nast

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Thomas Nast | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | September 27, 1840 Landau, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Confederation |

| Died | December 7, 1902 (aged 62) Guayaquil, Ecuador |

| Signature |  |

Albert Boime argues that:

- As a political cartoonist, Thomas Nast wielded more influence than any other artist of the 19th century. He not only enthralled a vast audience with boldness and wit, but swayed it time and again to his personal position on the strength of his visual imagination. Both Lincoln and Grant acknowledged his effectiveness in their behalf, and as a crusading civil reformer he helped destroy the corrupt Tweed Ring that swindled New York City of millions of dollars. Indeed, his impact on American public life was formidable enough to profoundly affect the outcome of every presidential election during the period 1864 to 1884.[3]

Contents

Early life and education

Nast was born in the barracks of Landau, Germany (now in Rhineland-Palatinate), the last child of Appolonia and Joseph Thomas Nast. He had a sister named Andie; two other siblings died before he was born. His father—a trombonist in the Bavarian 9th regiment band—held political convictions that put him at odds with the Bavarian government. In 1846, Joseph Nast left Landau, enlisting first on a French man-of-war and subsequently on an American ship.[4] He sent his wife and children to New York City, and at the end of his enlistment in 1850 he joined them there.[5]Nast attended school in New York City from the age of six to fourteen. He did poorly at his lessons, but his passion for drawing was apparent from an early age. In 1854 he was enrolled for about a year of study with Alfred Fredericks and Theodore Kaufmann, and then at the school of the National Academy of Design.[6][7] In 1856, he started working as a draftsman for Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.[8] His drawings appeared for the first time in Harper's Weekly on March 19, 1859,[9] when he illustrated a report exposing police corruption.[10]

Career

In February 1860, he went to England for the New York Illustrated News to depict one of the major sporting events of the era, the prize fight between the American John C. Heenan and the English Thomas Sayers[11] sponsored by George Wilkes, publisher of Wilkes' Spirit of the Times. A few months later, as artist for The Illustrated London News, he joined Garibaldi in Italy. Nast's cartoons and articles about the Garibaldi military campaign to unify Italy captured the popular imagination in the U.S. In February 1861, he arrived back in New York. In September of that year, he married Sarah Edwards, whom he had met two years earlier.He left the New York Illustrated News to work again, briefly, for Frank Leslie's Illustrated News.[12] In 1862, he became a staff illustrator for Harper's Weekly. In his first years with Harper's, Nast became known especially for compositions that appealed to the sentiment of the viewer. An example is "Christmas Eve" (1862), in which a wreath frames a scene of a soldier's praying wife and sleeping children at home; a second wreath frames the soldier seated by a campfire, gazing longingly at small pictures of his loved ones.[13] One of his most celebrated cartoons was "Compromise with the South" (1864), directed against those in the North who opposed the prosecution of the American Civil War.[14] He was known for drawing battlefields in border and southern states. These attracted great attention, and Nast was called by President Abraham Lincoln "our best recruiting sergeant".[15]

After the war, Nast strongly opposed the Reconstruction policy of President Andrew Johnson, who he depicted in a series of trenchant cartoons that marked "Nast's great beginning in the field of caricature".[16]

Style and themes

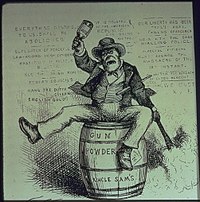

The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things, a cartoon by Thomas Nast depicting a drunken Irishman lighting a powder keg. Published in Harper's Weekly, September 2, 1871.

In the early part of his career, Nast used a brush and ink wash technique to draw tonal renderings onto the wood blocks that would be carved into printing blocks by staff engravers. The bold cross-hatching that characterized Nast's mature style resulted from a change in his method that began with a cartoon of June 26, 1869, which Nast drew onto the wood block using a pencil, so that the engraver was guided by Nast's linework. This change of style was influenced by the work of the English illustrator John Tenniel.[17]

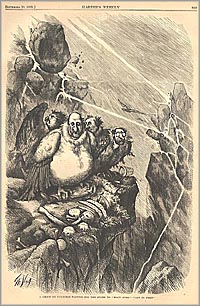

A recurring theme in Nast's cartoons is racism and anti-Catholicism. Nast was baptized a Catholic at the Sankt Maria Catholic Church in Landau,[18] and for a time received Catholic education in New York City.[19] When Nast converted to Protestantism remains unclear, but his conversion was likely formalized upon his marriage in 1861. (The family were practicing Episcopalians at St. Peter's in Morristown).[20] Nast considered the Roman Catholic Church a threat to American values, and often portrayed the Irish Catholics and Catholic Church leaders in hostile terms. According to his biographer, Fiona Deans Halloran, Nast was "intensely opposed to the encroachment of Catholic ideas into public education".[21] In 1871, one of his works, titled "The American River Ganges," portrayed Catholic bishops as crocodiles waiting to attack American school children.

Nast expressed his racist views of ethnic Irish by depicting them as violent drunks. He used the Irish as a symbol of mob violence, machine politics, and the exploitation of immigrants by political bosses.[22] Nast's emphasis on Irish violence may have originated in scenes he witnessed in his youth. Nast was physically small and had experienced bullying as a child.[23] In the neighborhood where he grew up, acts of violence by the Irish against African Americans were commonplace.[24] In 1863, he witnessed the New York City draft riots in which a mob composed mainly of Irish immigrants burned the Colored Orphan Asylum to the ground. His experiences may explain his sympathy for black Americans and his "antipathy to what he perceived as the brutish, uncontrollable Irish thug".[23]

In general, his political cartoons supported American Indians and Chinese Americans. He advocated the abolition of slavery, opposed racial segregation, and deplored the violence of the Ku Klux Klan. One of his more famous cartoons, entitled "Worse than Slavery," showed a despondent black family holding their dead child as a schoolhouse is destroyed by arson, as two members of the Ku Klux Klan and White League, paramilitary insurgent groups in the Reconstruction-era South, shake hands in their mutually destructive work against black Americans. Despite Nast's championing of minorities, Morton Keller writes that later in his career "racist stereotypes of blacks began to appear: comparable to those of the Irish."[25]

Nast introduced into American cartoons the practice of modernizing scenes from Shakespeare for a political purpose.

Campaign against the Tweed Ring

The Tammany Tiger Loose—"What are you going to do about it?", published in Harper's Weekly in November 1871, just before election day

Party politics

Harper's Weekly, and Nast, played an important role in the election of Ulysses Grant in 1868 and 1872; in the latter campaign, Nast's ridicule of Horace Greeley's candidacy was especially merciless.[30] After Grant's victory in 1872, Mark Twain wrote the artist a letter saying: "Nast, you more than any other man have won a prodigious victory for Grant—I mean, rather, for Civilization and Progress."[31] Nast became a close friend of President Grant and the two families shared regular dinners until Grant's death in 1885.Nast and his wife moved to Morristown, New Jersey in 1872 and there they raised a family that eventually numbered five children. In 1873, Nast toured the United States as a lecturer and a sketch-artist.[32] His activity on the lecture circuit made him wealthy.[33] Nast was for many years a staunch Republican.[34] Nast opposed inflation of the currency, notably with his famous rag-baby cartoons, and he played an important part in securing Rutherford B. Hayes’ presidential election in 1876. Hayes later remarked that Nast was "the most powerful, single-handed aid [he] had",[35] but Nast quickly became disillusioned with President Hayes, whose policy of Southern pacification he opposed.

Interior Secretary Schurz cleaning house, Harper's Weekly, January 26, 1878

Between 1877 and 1884, Nast's work appeared only sporadically in Harper's. Although his sphere of influence was diminishing, from this period date many of his pro-Chinese immigration drawings; Nast was one of the few editorial artists who took up for the cause of the Chinese in America.[40]

Portrait of Thomas Nast from Harpers Weekly, 1867

In 1884, Curtis and Nast agreed that they could not support the Republican candidate James G. Blaine, a proponent of high tariffs and the spoils system who they perceived as personally corrupt.[43] Instead they became Mugwumps by supporting the Democratic candidate, Grover Cleveland, whose platform of civil service reform appealed to them. Nast's cartoons helped Cleveland become the first Democrat to be elected President since 1856. In the words of the artist's grandson, Thomas Nast St Hill, "it was generally conceded that Nast's support won Cleveland the small margin by which he was elected. In this his last national political campaign, Nast had, in fact, 'made a president.'"[44]

Nast's tenure at Harper's Weekly ended with his Christmas illustration of December 1886. It was said by the journalist Henry Watterson that "in quitting Harper's Weekly, Nast lost his forum: in losing him, Harper's Weekly lost its political importance."[45] Fiona Deans Halloran says "the former is true to a certain extent, the latter unlikely."[46]

Nast lost most of his fortune in 1884, after investing in a banking and brokerage firm operated by the swindler Ferdinand Ward. In need of income, Nast returned to the lecture circuit in 1884 and 1887.[47] Although these tours were successful, they were less renumerative than the lecture series of 1873.[48]

After Harper's Weekly

In 1890, Nast published Thomas Nast's Christmas Drawings for the Human Race.[6] He contributed cartoons in various publications, notably the Illustrated American, but was unable to regain his earlier popularity. His mode of cartooning had come to be seen as outdated—a more relaxed style exemplified by the work of Joseph Keppler was in vogue.[49] Health problems, which included pain in his hands which had troubled him since the 1870s, affected his ability to work.In 1892, he took control of a failing magazine, the New York Gazette, and renamed it Nast's Weekly. Now returned to the Republican fold, Nast used the Weekly as a vehicle for his cartoons supporting Benjamin Harrison for president. The magazine had little impact and ceased publication seven months after it began, shortly after Harrison's defeat.[50]

The failure of Nast's Weekly left Nast with few financial resources. He received a few commissions for oil paintings, and drew book illustrations. In 1902, he applied for a job in the State Department, hoping to secure a consular position in western Europe.[51] Although no such position was available, President Theodore Roosevelt was an admirer of the artist and offered him an appointment as the United States' Consul General to Guayaquil, Ecuador in South America.[51] Nast accepted the position and traveled to Ecuador on July 1, 1902.[51] During a subsequent yellow fever outbreak, Nast remained on the job, helping numerous diplomatic missions and businesses escape the contagion. He contracted the disease and died on December 7 of that year.[6] His body was returned to the United States, where he was interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York.

Legacy

Nast's Santa Claus on the cover of the January 3, 1863, issue of Harper's Weekly

- Republican Party elephant[53]

- Democratic Party donkey (although the donkey was associated with the Democrats as early as 1837, Nast popularized the representation[54])

- Tammany Hall tiger, a symbol of Boss Tweed's political machine

- Columbia, a graceful image of the Americas as a woman, usually in flowing gown and tiara, carrying a sword to defend the downtrodden.

- Uncle Sam, a lanky avuncular personification of the United States (first drawn in the 1830s; Nast and John Tenniel added the goatee).

- John Confucius, a variation of John Chinaman, a traditional caricature of a Chinese Immigrant.

- The Fight at Dame Europa's School, 1871

- Peace In Union, a 9'x12' oil depicting the surrender of General Robert E. Lee to General U.S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse in April 1865. The painting was a commission from Herman Kohlsaat in 1894. Upon its completion in 1895 it was presented as a gift to the citizens of Galena, Illinois.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered