In Hawaii, a healthcare system apart

The state's trailblazing system and widespread insurance coverage mean its residents are some of the nation's healthiest. But that only underscores the disparities across the U.S.

|

Myra Williams, a breast

cancer survivor, does yoga behind her home in Kailua, Hawaii. Her cancer

was discovered during a routine mammogram. Such screenings are readily

available in much of the state.

(Christina House / For The Times / September 4, 2013)

|

HONOLULU — When the giant

kapok and nawa trees that tower over the Queen's Medical Center in

downtown Honolulu were planted more than a century ago, Hawaii faced a

health crisis.

Many on the islands, including the queen who founded the hospital in 1859, feared that native Hawaiians, devastated by smallpox, measles and other illnesses brought by foreigners, were in danger of dying off completely.

Today, the people who walk under these trees are some of the healthiest in America.

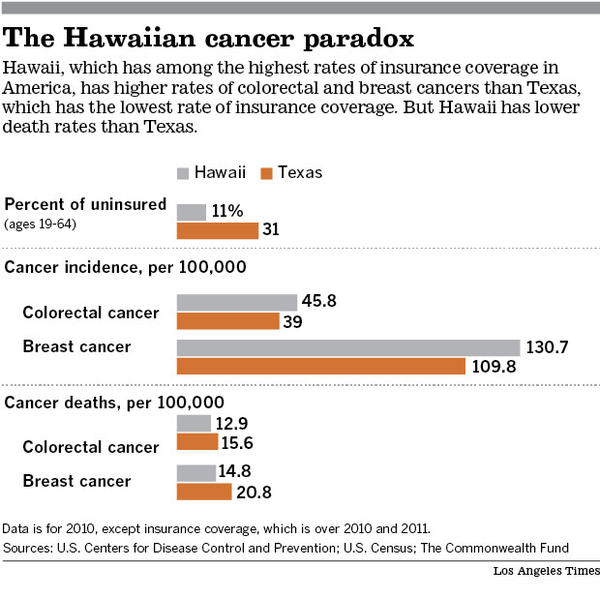

Hawaiians live longer than their counterparts on the mainland. They die less frequently from common diseases, such as breast and colon cancers, even though these cancers occur more often here than in most other states. They also pay less for their care; the state's healthcare costs are among the lowest in the country.

Hawaii's success owes much to the state's trailblazing health system and its long history of near-universal health insurance.

Forty years ago, the state became the first to require employers to provide health benefits, codifying a tradition that grew out of Hawaii's agrarian past, when sugar and pineapple plantations employed doctors to care for their workers.

That system has led to some of the highest rates of coverage and best access to medical care in the country.

"There has always been a mentality here that if you are sick, you go to the doctor. It's just part of the culture," said Myra Williams, 64, who has lived in Hawaii for 35 years and was recently treated successfully for early-stage breast cancer.

Nearly 99% of the patients at the cancer center at Queen's have health coverage, a level unheard of at most urban medical centers on the mainland.

Healthcare in America is a tale of two countries.

Residents of the healthiest communities live as much as 14 years longer on average than those in unhealthy places. They are a third less likely to die from treatable illnesses such as breast cancer, childhood measles and diabetes, according to data from the Commonwealth Fund, a foundation dedicated to improving the healthcare system.

Big variations in poverty, education and diet may explain part of this divide. In Hawaii, the large share of residents of East Asian descent, who have lower mortality rates for many diseases, may also have an impact.

But differences in local health systems nationwide — including disparities in insurance coverage — also likely play an important role, according to an analysis of local and national healthcare data, a review of academic studies, interviews with scores of experts, and visits to communities across the country.

Nearly everyone is covered in the nation's healthiest places, including Hawaii, Massachusetts and parts of the Upper Midwest. By contrast, fewer than 7 in 10 working-age adults have health insurance in parts of Texas, Florida and the Deep South — areas with some of the highest rates of death from preventable illnesses.

In Texas, which has the lowest rate of insurance coverage in the nation, residents are 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than they are in Hawaii, according to federal cancer data.

These disparities may grow even larger in coming years as the Affordable Care Act is implemented unevenly around the country. Although the law offers states the opportunity to guarantee their residents insurance, only about half the states have elected to do so.

In Hawaii, health insurance has reshaped healthcare, from the smallest clinics to major urban hospitals, affecting when patients are treated and even how they recover.

On Oahu's North Shore, a rural stretch of Hawaii's most populous island once covered with sugar cane plantations, Dr. Randall Suzuka sees many of the routine complaints common to a community physician's office.

One morning at Haleiwa Family Health Center, Suzuka, who has worked there since 1986, tended to an elderly woman having trouble sleeping, a municipal worker with a strained neck and a 10-month-old who had cut her finger on broken glass.

But his office, originally opened by a former plantation doctor, differs from many medical practices in one key way: He rarely needs to discuss skipping care with a patient just because the person doesn't have adequate insurance.

"It's just not something we talk about," said Suzuka, a fifth-generation Japanese American whose family came to work on the plantations.

Nationwide in 2012, more than 4 in 10 working-age adults did not seek needed medical care, skipped a recommended test or didn't fill a prescription because of concerns about cost, according to a survey by the Commonwealth Fund. Delayed care is even more common among uninsured adults, with two-thirds reporting they had put off a doctor's visit or a prescription.

Insurance status can make a big difference in how soon cancers are found.

Uninsured women, for example, are two and a half times as likely to be diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer as women who have private health coverage, according to an American Cancer Society study.

In many parts of Hawaii, cancer screenings are readily available.

Kaiser Permanente, one of the state's leading insurers, screens more than 80% of its eligible members for breast cancer, among the highest rates in the nation. Kaiser is also stepping up efforts to reach patients, with a mobile mammography van that travels around the mostly rural Big Island of Hawaii.

Early detection and early treatment — rarer in other parts of the country — make cancer easier to treat in Hawaii, said Dr. Clayton Chong, a senior oncologist at Queen's who trained at the renowned M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Queen's Cancer Center gets almost half of all new cancer patients in the state.

Many are like Eric Martinson. The father of two young sons, Martinson, 51, was diagnosed with lymphoma last summer after his dentist discovered an abnormal growth in his jaw during a routine cleaning.

The cancer was found early, as is often the case in Hawaii. Martinson was given chemotherapy, and follow-up tests showed the cancer hadn't spread to any organs.

To ensure Martinson was out of danger, Chong brought him back in for a bone marrow biopsy.

"This may hurt a little," Chong warned gently, as he rolled Martinson onto his stomach and felt for the back of his pelvic bone. After cleaning the skin and injecting a local anesthetic, Chong plunged an awl-like tool into Martinson's back. Rocking the probe back and forth, he pushed it through the bone. Martinson groaned into a pillow.

"Do you know how to count in Hawaiian?" Chong asked to distract his patient. "How about backward?"

Chong carefully pulled a nub of bloody marrow from the pelvic bone and smeared it on a glass slide. Subsequent testing showed no sign of cancer.

"I consider myself really blessed," Martinson said. He has since returned to work, his cancer in remission.

Hawaii's extensive insurance coverage also allows Queen's to check up more easily on patients after they finish treatment, which is key to preventing a recurrence.

Queen's is among a group of centers nationally that operate so-called survivorship programs, which coordinate follow-up care for patients as they adjust to life after treatment.

The survivorship services at Queen's are offered at no cost to patients. That would be difficult if the cancer center had to serve more patients without coverage, said Darlena Chadwick, the medical center's vice president for patient care.

"Insurance makes a difference," she said.

The 40-year-old foundation of the state's system is the Hawaii Prepaid Health Care Act. It requires companies with more than 10 employees working at least 20 hours a week to provide basic health benefits.

But the law, which places more requirements on employers than the federal law that President Obama signed in 2010, has not solved all the state's health problems.

Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders, who are generally poorer, have far worse health outcomes despite efforts to address the disparity.

The state's safety-net providers, including clinics that serve low-income Hawaiians, still face strains from patients who can't afford health coverage.

But even as the rest of the country continues to fight over Obama's law, there has been virtually no talk in Hawaii about repealing the Prepaid Health Care Act, even among business leaders.

"Like everywhere, employers have concerns about costs," said Sherry Menor-McNamara, president of the state Chamber of Commerce. "But over the years, businesses have come to see the important impact of the law in improving health."

Widespread insurance coverage has had another, more intangible benefit, says Jennifer Diesman, an executive with Hawaii Medical Services Assn., the state's dominant insurer.

Unlike in many states, where separate and unequal medical systems care for the insured and uninsured, "everyone here uses the same doctors and the same hospitals," Diesman said. "It creates a more egalitarian spirit."

A similar consensus solidified behind health reforms in Massachusetts, which in 2006 became the second state to create a system for guaranteeing coverage. Massachusetts' law was the model for the Affordable Care Act.

Half of the country is moving ahead with the federal program for expanding insurance, including Nevada, Arkansas, Kentucky and West Virginia — states with some of the worst health outcomes.

Those states will be a test of how much expanded coverage can improve a community's health.

But many other states with poorly performing health systems, including Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama, have rejected federal aid to expand their Medicaid programs and guarantee insurance for their residents. Elected leaders in those states say the aid comes with too many federal mandates.

Restricting coverage baffles many who have worked in Hawaii's healthcare system.

"We learned a long time ago that when you give someone access to medical care, they get healthier," said Dr. Jack Lewin, a former director of Hawaii's Health Department and former head of the American College of Cardiology.

"Someday, maybe the rest of the country will learn that."

noam.levey@latimes.com

noam.levey@latimes.com

Support for this series came from the Assn. of Health Care Journalists' Reporting Fellowships on Health Care Performance, funded by the Commonwealth Fund. David Radley at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Robert C. Wild and Dr. Ashish Jha at the Harvard School of Public Health assisted with data analysis.

Today, the people who walk under these trees are some of the healthiest in America.

Hawaiians live longer than their counterparts on the mainland. They die less frequently from common diseases, such as breast and colon cancers, even though these cancers occur more often here than in most other states. They also pay less for their care; the state's healthcare costs are among the lowest in the country.

Hawaii's success owes much to the state's trailblazing health system and its long history of near-universal health insurance.

Forty years ago, the state became the first to require employers to provide health benefits, codifying a tradition that grew out of Hawaii's agrarian past, when sugar and pineapple plantations employed doctors to care for their workers.

That system has led to some of the highest rates of coverage and best access to medical care in the country.

"There has always been a mentality here that if you are sick, you go to the doctor. It's just part of the culture," said Myra Williams, 64, who has lived in Hawaii for 35 years and was recently treated successfully for early-stage breast cancer.

Nearly 99% of the patients at the cancer center at Queen's have health coverage, a level unheard of at most urban medical centers on the mainland.

Healthcare in America is a tale of two countries.

Residents of the healthiest communities live as much as 14 years longer on average than those in unhealthy places. They are a third less likely to die from treatable illnesses such as breast cancer, childhood measles and diabetes, according to data from the Commonwealth Fund, a foundation dedicated to improving the healthcare system.

Big variations in poverty, education and diet may explain part of this divide. In Hawaii, the large share of residents of East Asian descent, who have lower mortality rates for many diseases, may also have an impact.

But differences in local health systems nationwide — including disparities in insurance coverage — also likely play an important role, according to an analysis of local and national healthcare data, a review of academic studies, interviews with scores of experts, and visits to communities across the country.

Nearly everyone is covered in the nation's healthiest places, including Hawaii, Massachusetts and parts of the Upper Midwest. By contrast, fewer than 7 in 10 working-age adults have health insurance in parts of Texas, Florida and the Deep South — areas with some of the highest rates of death from preventable illnesses.

In Texas, which has the lowest rate of insurance coverage in the nation, residents are 40% more likely to die from breast cancer than they are in Hawaii, according to federal cancer data.

These disparities may grow even larger in coming years as the Affordable Care Act is implemented unevenly around the country. Although the law offers states the opportunity to guarantee their residents insurance, only about half the states have elected to do so.

In Hawaii, health insurance has reshaped healthcare, from the smallest clinics to major urban hospitals, affecting when patients are treated and even how they recover.

On Oahu's North Shore, a rural stretch of Hawaii's most populous island once covered with sugar cane plantations, Dr. Randall Suzuka sees many of the routine complaints common to a community physician's office.

One morning at Haleiwa Family Health Center, Suzuka, who has worked there since 1986, tended to an elderly woman having trouble sleeping, a municipal worker with a strained neck and a 10-month-old who had cut her finger on broken glass.

But his office, originally opened by a former plantation doctor, differs from many medical practices in one key way: He rarely needs to discuss skipping care with a patient just because the person doesn't have adequate insurance.

"It's just not something we talk about," said Suzuka, a fifth-generation Japanese American whose family came to work on the plantations.

Nationwide in 2012, more than 4 in 10 working-age adults did not seek needed medical care, skipped a recommended test or didn't fill a prescription because of concerns about cost, according to a survey by the Commonwealth Fund. Delayed care is even more common among uninsured adults, with two-thirds reporting they had put off a doctor's visit or a prescription.

Insurance status can make a big difference in how soon cancers are found.

Uninsured women, for example, are two and a half times as likely to be diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer as women who have private health coverage, according to an American Cancer Society study.

In many parts of Hawaii, cancer screenings are readily available.

Kaiser Permanente, one of the state's leading insurers, screens more than 80% of its eligible members for breast cancer, among the highest rates in the nation. Kaiser is also stepping up efforts to reach patients, with a mobile mammography van that travels around the mostly rural Big Island of Hawaii.

Early detection and early treatment — rarer in other parts of the country — make cancer easier to treat in Hawaii, said Dr. Clayton Chong, a senior oncologist at Queen's who trained at the renowned M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Queen's Cancer Center gets almost half of all new cancer patients in the state.

Many are like Eric Martinson. The father of two young sons, Martinson, 51, was diagnosed with lymphoma last summer after his dentist discovered an abnormal growth in his jaw during a routine cleaning.

The cancer was found early, as is often the case in Hawaii. Martinson was given chemotherapy, and follow-up tests showed the cancer hadn't spread to any organs.

To ensure Martinson was out of danger, Chong brought him back in for a bone marrow biopsy.

"This may hurt a little," Chong warned gently, as he rolled Martinson onto his stomach and felt for the back of his pelvic bone. After cleaning the skin and injecting a local anesthetic, Chong plunged an awl-like tool into Martinson's back. Rocking the probe back and forth, he pushed it through the bone. Martinson groaned into a pillow.

"Do you know how to count in Hawaiian?" Chong asked to distract his patient. "How about backward?"

Chong carefully pulled a nub of bloody marrow from the pelvic bone and smeared it on a glass slide. Subsequent testing showed no sign of cancer.

"I consider myself really blessed," Martinson said. He has since returned to work, his cancer in remission.

Hawaii's extensive insurance coverage also allows Queen's to check up more easily on patients after they finish treatment, which is key to preventing a recurrence.

Queen's is among a group of centers nationally that operate so-called survivorship programs, which coordinate follow-up care for patients as they adjust to life after treatment.

The survivorship services at Queen's are offered at no cost to patients. That would be difficult if the cancer center had to serve more patients without coverage, said Darlena Chadwick, the medical center's vice president for patient care.

"Insurance makes a difference," she said.

The 40-year-old foundation of the state's system is the Hawaii Prepaid Health Care Act. It requires companies with more than 10 employees working at least 20 hours a week to provide basic health benefits.

But the law, which places more requirements on employers than the federal law that President Obama signed in 2010, has not solved all the state's health problems.

Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders, who are generally poorer, have far worse health outcomes despite efforts to address the disparity.

The state's safety-net providers, including clinics that serve low-income Hawaiians, still face strains from patients who can't afford health coverage.

But even as the rest of the country continues to fight over Obama's law, there has been virtually no talk in Hawaii about repealing the Prepaid Health Care Act, even among business leaders.

"Like everywhere, employers have concerns about costs," said Sherry Menor-McNamara, president of the state Chamber of Commerce. "But over the years, businesses have come to see the important impact of the law in improving health."

Widespread insurance coverage has had another, more intangible benefit, says Jennifer Diesman, an executive with Hawaii Medical Services Assn., the state's dominant insurer.

Unlike in many states, where separate and unequal medical systems care for the insured and uninsured, "everyone here uses the same doctors and the same hospitals," Diesman said. "It creates a more egalitarian spirit."

A similar consensus solidified behind health reforms in Massachusetts, which in 2006 became the second state to create a system for guaranteeing coverage. Massachusetts' law was the model for the Affordable Care Act.

Half of the country is moving ahead with the federal program for expanding insurance, including Nevada, Arkansas, Kentucky and West Virginia — states with some of the worst health outcomes.

Those states will be a test of how much expanded coverage can improve a community's health.

But many other states with poorly performing health systems, including Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama, have rejected federal aid to expand their Medicaid programs and guarantee insurance for their residents. Elected leaders in those states say the aid comes with too many federal mandates.

Restricting coverage baffles many who have worked in Hawaii's healthcare system.

"We learned a long time ago that when you give someone access to medical care, they get healthier," said Dr. Jack Lewin, a former director of Hawaii's Health Department and former head of the American College of Cardiology.

"Someday, maybe the rest of the country will learn that."

Support for this series came from the Assn. of Health Care Journalists' Reporting Fellowships on Health Care Performance, funded by the Commonwealth Fund. David Radley at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Robert C. Wild and Dr. Ashish Jha at the Harvard School of Public Health assisted with data analysis.

We've upgraded our reader commenting system. Learn more about the new features.

Los

Angeles Times welcomes civil dialogue about our stories; you must

register with the site to participate. We filter comments for language

and adherence to our Terms of Service, but not for factual accuracy. By

commenting, you agree to these legal terms. Please flag inappropriate comments.

Having technical problems? Check here for guidance.

| Advertisement |

|

|

- Go inside secret supper clubs where intrigue is served hot 04/05/2014, 12:00 a.m.

- Make nut milk - plant based and, oh, so easy 04/05/2014, 12:00 a.m.

- 13 underground supper clubs in the L.A. area 04/05/2014, 12:00 a.m.

- Three L.A. restaurants revive delicious octopus memories 04/05/2014, 12:00 a.m.

- El Monte police shoot, kill pit bull after attack 04/04/2014, 6:49 p.m.

- Recipe: Mendocino Farms' curried couscouswith roasted cauliflower - L.A. Times - Food & Dining 04/05/2014, 12:00 a.m.

- Three L.A. restaurants revive delicious octopus memories - L.A. Times - Food & Dining 04/05/2014, 12:00 a.m.

- Make nut milk - plant based and, oh, so easy - L.A. Times - Food & Dining 04/05/2014, 12:00 a.m.

- 13 underground supper clubs in the L.A. area - L.A. Times - Food & Dining 04/05/2014, 12:00 a.m.

- Go inside secret supper clubs where intrigue is served hot - L.A. Times - Food & Dining 04/05/2014, 12:00 a.m.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered