August Wilson

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the late-20th-century writer. For the late-19th-century writer August J. Evans Wilson, see Augusta Jane Evans. For the United States Navy sailor, see August Wilson (Medal of Honor).

| August Wilson | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Frederick August Kittel April 27, 1945 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA |

| Died | October 2, 2005 (aged 60) Seattle, Washington, USA |

| Occupation | Author, playwright |

| Nationality | United States |

| Spouse | Constanza Romero (1994–2005) Judy Oliver (1981–1990) Brenda Burton (1969–1972) |

| Information | |

| Magnum opus | The Pittsburgh Cycle |

| Awards | Pulitzer Prize for Drama (1987, 1990) |

Contents

Life

Childhood

Wilson's maternal grandmother walked from North Carolina to Pennsylvania in search of a better life. Wilson was born Frederick August Kittel, Jr. in the Hill District of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the fourth of six children, to Sudeten-German immigrant baker/pastry cook, Frederick August Kittel, Sr. and Daisy Wilson, an African American cleaning woman, from North Carolina.[1] Wilson's mother raised the children alone until he was five in a two-room apartment above a grocery store at 1727 Bedford Avenue; his father was mostly absent from his childhood. Wilson would go on to write under his mother's surname. The economically depressed neighborhood in which he was raised was inhabited predominantly by black Americans, and Jewish and Italian immigrants. Wilson's mother divorced and married David Bedford in the 1950s and the family moved from the Hill District to the then predominantly white working-class neighborhood of Hazelwood, where they encountered racial hostility; bricks were thrown through a window at their new home. They were soon forced out of their house and on to their next home.[2]Wilson was the only African-American student at the Central Catholic High School in 1959 where he was soon driven away by threats and abuse.[1]He then attended Connelley Vocational High School, but found the curriculum unchallenging. He dropped out of Gladstone High School in the 10th grade in 1960 after his teacher accused him of plagiarizing a 20-page paper he wrote on Napoleon I of France. Wilson hid his decision from his mother because he did not want to disappoint her. At the age of 16, he began working menial jobs and that allowed him to meet a wide variety of people, some of whom he later based his characters on, such as Sam in The Janitor (1985).

Wilson made such extensive use of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh to educate himself that it later awarded him a degree, the only such one it has bestowed. Wilson, who had learned to read at age four, began reading black writers at the library at age 12 and spent the remainder of his teen years educating himself by reading Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, Arna Bontemps, and others.[2]

Career

By this time, Wilson knew that he wanted to be a writer, but this created tension with his mother, who wanted him to become a lawyer. She forced him to leave the family home and he enlisted in the United States Army for a three-year stint in 1962, but left after one year and went back to working various odd jobs as a porter, short-order cook, gardener, and dishwasher.Frederick August Kittel, Jr. changed his name to August Wilson to honor his mother after his father's death in 1965. That same year he discovered the blues as sung by Bessie Smith and bought a stolen typewriter for $10, which he would often pawn when money was tight.[3] At 20 he decided he was a poet and submitted his poetry to such magazines as Harpers.[1] He began to write in bars, the local cigar store and cafes, on table napkins and on longhand yellow note pads, absorbing the voices and characters around him. He liked to write on cafe napkins because, he said, it freed him up and made him less self-conscious as a writer. He would then gather the notes and type them up at home.[1] Gifted with a talent for catching dialects and accents, Wilson had an "astonishing memory," which he put to full use during his career. He slowly learned not to censor the language he heard when incorporating it into his work.[4]

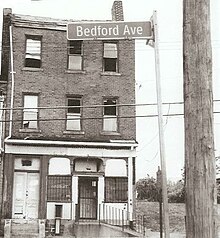

Wilson's childhood home at 1727 Bedford Avenue in Pittsburgh

In 1968, Wilson co-founded the Black Horizon Theater in the Hill District of Pittsburgh along with his friend Rob Penny.[1] His first play, Recycling, was performed for audiences in small theaters, schools and public housing community centers for 50 cents a ticket. Among these early efforts was Jitney which he revised more than two decades later as part of his 10-play cycle on 20th century Pittsburgh.[2] He had no directing experience.[1] He recalled "Someone had looked around and said, 'Who’s going to be the director?' I said, 'I will.' I said that because I knew my way around the library. So I went to look for a book on how to direct a play. I found one called The Fundamentals of Play Directing and checked it out."[4]

In 1976 Vernell Lillie, who had founded the Kuntu Repertory Theatre at the University of Pittsburgh two years earlier, directed Wilson's The Homecoming. That same year Wilson saw Sizwe Banzi is Dead at the Pittsburgh Public Theater, his first professional play. Wilson, Penny, and poet Maisha Baton also started the Kuntu Writers Workshop to bring African-American writers together and to assist them in publication and production. Both organizations are still active.

In 1978 Wilson moved to Saint Paul, Minnesota at the suggestion of his friend director Claude Purdy, who helped him secure a job writing educational scripts for the Science Museum of Minnesota.[1] In 1980 he received a fellowship for The Playwrights' Center in Minneapolis. He quit the Museum in 1981, but continued writing plays. For three years, he was a part-time cook for the Little Brothers of the Poor. Wilson had a long association with the Penumbra Theatre Company of St Paul, which gave the premieres of some Wilson plays. Fullerton Street which has been unproduced and unpublished, was written in 1980. It follows the Joe Louis/Billy Conn fight in 1940 and the loss of values attendant on the Great Migration to the urban North.[2]

In 1987, Saint Paul's mayor George Latimer named May 27 "August Wilson Day." He was honored because he was the only person to both come from Minnesota and win a Pulitzer Prize.[2]

In 1990 Wilson left St Paul after getting divorced and moved to Seattle. There he would develop a relationship with Seattle Repertory Theatre, which would become the only theater in the country to produce all of the works in his ten-play cycle and his one-man show How I Learned What I Learned.[2]

Although he was a writer dedicated to writing for theater, a Hollywood studio proposed filming Wilson's play Fences. He insisted that a black director be hired for the film, saying "I declined a white director not on the basis of race but on the basis of culture. White directors are not qualified for the job. The job requires someone who shares the specifics of the culture of black Americans." The film was never made.

Wilson received many honorary degrees, including an honorary Doctor of Humanities from the University of Pittsburgh, where he served as a member of the University's Board of Trustees from 1992 until 1995.[5]

Work

Wilson's best known plays are Fences (1985) (which won a Pulitzer Prize and a Tony Award), The Piano Lesson (1990) (a Pulitzer Prize and the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award), Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, and Joe Turner's Come and Gone.Wilson stated that he was most influenced by "the four Bs": blues music, the Argentine novelist and poet Jorge Luis Borges, the playwright Amiri Baraka and the painter Romare Bearden.[1] He went on to add writers Ed Bullins and James Baldwin to the list. He noted "From Borges, those wonderful gaucho stories from which I learned that you can be specific as to a time and place and culture and still have the work resonate with the universal themes of love, honor, duty, betrayal, etc. From Amiri Baraka, I learned that all art is political, although I don't write political plays. From Romare Bearden I learned that the fullness and richness of everyday life can be rendered without compromise or sentimentality." [1] He valued Bullins and Baldwin for their honest representations of everyday life.[4]

Like Bearden, Wilson worked with collage techniques in writing: " I try to make my plays the equal of his canvases. In creating plays I often use the image of a stewing pot in which I toss various things that I’m going to make use of—a black cat, a garden, a bicycle, a man with a scar on his face, a pregnant woman, a man with a gun." On the meaning of his work Wilson stated "I once wrote this short story called 'The Best Blues Singer in the World,' and it went like this— “The streets that Balboa walked were his own private ocean, and Balboa was drowning.” End of story. That says it all. Nothing else to say. I’ve been rewriting that same story over and over again. All my plays are rewriting that same story."[4]

The Pittsburgh Cycle

Wilson's "Pittsburgh Cycle," also often referred to as his "Century Cycle," consists of ten plays—nine of which are set in Pittsburgh's Hill District, an African-American neighborhood that takes on a mythic literary significance like Thomas Hardy's Wessex, William Faulkner's Yoknapatawpha County, or Irish playwright Brian Friel's Ballybeg. The plays are each set in a different decade and aim to sketch the Black experience in the 20th century and "raise consciousness through theater” and echo "the poetry in the everyday language of black America".[4] He was fascinated by the power of theater as a medium where a community at large could come together to bear witness to events and currents unfolding.[4]Wilson noted:

"I think my plays offer (white Americans) a different way to look at black Americans," he told The Paris Review. "For instance, in 'Fences' they see a garbageman, a person they don't really look at, although they see a garbageman every day. By looking at Troy's life, white people find out that the content of this black garbageman's life is affected by the same things - love, honor, beauty, betrayal, duty. Recognizing that these things are as much part of his life as theirs can affect how they think about and deal with black people in their lives."[1]Although the plays of the cycle are not strictly connected to the degree of a serial story, some characters appear (at various ages) in more than one of the cycle's plays. Children of characters in earlier plays may appear in later plays. The character most frequently mentioned in the cycle is Aunt Ester, a "washer of souls". She is reported to be 285 years old in Gem of the Ocean, which takes place in her home at 1839 Wylie Avenue, and 322 in Two Trains Running. She dies in 1985, during the events of King Hedley II. Much of the action of Radio Golf revolves around the plan to demolish and redevelop that house, some years after her death. The plays often include an apparently mentally impaired oracular character (different in each play)—for example, Hedley [Sr.] in Seven Guitars, Gabriel in Fences or Hambone in Two Trains Running.

- 1900s - Gem of the Ocean (2003)

- 1910s - Joe Turner's Come and Gone (1988)

- 1920s - Ma Rainey's Black Bottom (1984) - set in Chicago

- 1930s - The Piano Lesson (1990) - Pulitzer Prize[6]

- 1940s - Seven Guitars (1995)

- 1950s - Fences (1987) - Pulitzer Prize[6]

- 1960s - Two Trains Running (1991)

- 1970s - Jitney (1982)

- 1980s - King Hedley II (1999)

- 1990s - Radio Golf (2005)

Personal life

Wilson was married three times. His first marriage was to Brenda Burton from 1969 to 1972. They had one daughter, Sakina Ansari, born 1970. In 1981 he was married to Judy Oliver, a social worker, and divorced in 1990. He married again in 1994 and was survived by his third wife, costume designer, Constanza Romero, whom he met on the set of "The Piano Lesson". Together they had a daughter, Azula Carmen Wilson.[1] Wilson was also survived by siblings Freda Ellis, Linda Jean Kittel, Donna Conley, Barbara Jean Wilson, Edwin Kittel and Richard Kittel.Wilson reported that he had been diagnosed with liver cancer in June 2005 and been given three to five months to live. He died on October 2, 2005 at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, and was interred at Greenwood Cemetery, Pittsburgh on October 8, 2005.

Legacy

The childhood home of Wilson and his six siblings, at 1727 Bedford Avenue in Pittsburgh was declared a historic landmark by the State of Pennsylvania on May 30, 2007.[10] On February 26, 2008, Pittsburgh City Council placed the house on the List of City of Pittsburgh historic designations. On April 30, 2013, the August Wilson House was added to the National Register of Historic Places.[11]In Pittsburgh, there is an August Wilson Center for African American Culture.

On October 16, 2005, fourteen days after Wilson's death, the Virginia Theatre in New York City's Broadway Theater District was renamed the August Wilson Theatre. It is the first Broadway theatre to bear the name of an African-American.[12]

The vacated Republican Street between Warren Avenue N. and 2nd Avenue N. on the Seattle Center grounds has been renamed August Wilson Way.[13]

Honors and awards

- 1985: New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play – Ma Rainey's Black Bottom

- 1986: Whiting Writers' Award - Ma Rainey's Black Bottom

- 1986: American Theatre Critics' Association Award - Fences

- 1987: Drama Desk Award for Outstanding New Play – Fences

- 1987: New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play – Fences

- 1987: Pulitzer Prize for Drama – Fences

- 1987: Tony Award for Best Play – Fences

- 1987: Outer Critics Circle Award - Fences

- 1987: Artist of the Year by Chicago Tribune

- 1988: Literary Lion Award from the New York Public Library

- 1988: New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play – Joe Turner's Come and Gone

- 1990: Governor's Awards for Excellence in the Arts and Distinguished Pennsylvania Artists

- 1990: Drama Desk Award for Outstanding New Play – The Piano Lesson

- 1990: New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play – The Piano Lesson

- 1990: Pulitzer Prize for Drama – The Piano Lesson

- 1991: Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame award

- 1992: American Theatre Critics' Association Award – Two Trains Running

- 1992: New York Drama Critics Circle Citation for Best American Play – Two Trains Running

- 1992: Clarence Muse Award

- 1996: New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play – Seven Guitars

- 1999: National Humanities Medal

- 2000: New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play – Jitney

- 2000: Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding Off-Broadway Play – Jitney

- 2002: Olivier Award for Best new Play – Jitney

- 2004: The 10th Annual Heinz Award in Arts and Humanities[14]

- 2004: The U.S. Comedy Arts Festival Freedom of Speech Award

- 2005: Make Shift Award at the U.S. Confederation of Play Writers

Plays

- Recycle, 1973 (produced in Pittsburgh, PA)

- Fullerton Street, 1980

- Black Bart and the Sacred Hills, 1977 (produced St. Paul, 1981)

- Jitney (1982)

- Ma Rainey's Black Bottom (1984)

- The Homecoming, 1989

- Fences (1987) - Pulitzer Prize[6]

- Joe Turner's Come and Gone (1984)

- The Coldest Day of the Year, 1989

- The Piano Lesson (1990) - Pulitzer Prize[6]

- Two Trains Running (1991)

- Seven Guitars (1995)

- King Hedley II (1999)

- How I Learned What I Learned (2002–03, Seattle)

- Gem of the Ocean (2003)

- Radio Golf (2005)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered