Microsoft’s onetime antitrust nemesis now fighting Google in Europe

Gary Reback, who in the 1990s persuaded the Justice Department to sue Microsoft, is still fighting the tech industry’s most powerful companies. Now that means pressing Europe’s regulators to take a hard line against some of Google’s practices.

MENLO PARK, Calif. — In the 1990s, Gary Reback was known as Silicon Valley’s dragon slayer, a lawyer who persuaded the Justice Department to sue Microsoft, accusing it of abusing its dominant position in desktop computers. Newspapers and magazines called him “Bill Gates’ worst nightmare.”

Reback still makes his living fighting the technology industry’s most powerful companies, but today he is up against Google, not Microsoft. And instead of flying to Washington, D.C., he goes to Europe — a shift that, at least in Reback’s view, reflects how cozy Google has become with U.S. politicians.

“There isn’t anybody in Silicon Valley who thinks that this administration is ever going to do anything that really hurts Google,” said Reback, a lawyer at Carr & Ferrell in Menlo Park.

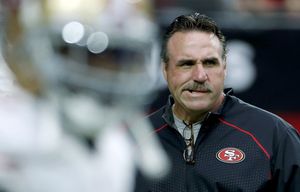

Gary Reback

Age: 66

Education: Yale University, Stanford Law School

Quote: “There isn’t anybody in Silicon Valley who thinks that this administration is ever going to do anything that really hurts Google.”

Source: The New York Times

That view could be tested, as the Federal Trade Commission recently opened an inquiry into whether Google uses its Android operating software to bolster the dominance of products like its search engine. The investigation is still early but will be closely scrutinized by rivals who were incensed that an earlier FTC investigation did not result in charges against the company.

Most Read Stories

In the meantime, Brussels has become the venue of choice for U.S. antitrust lawyers and technology companies, which find European authorities more receptive to their complaints that Google is using the power of its search business to snuff out competitors.

In April, the European Commission filed charges that Google favors its own specialty or “vertical” sites over rival sites, like NexTag, a comparison shopping service that is one of Reback’s clients. Google responded in August and lawyers expect the European Commission to issue a judgment as soon as late this year.

Whatever happens, Google can expect to hear a lot more from Reback. The European Commission has accelerated a separate investigation of Android — Reback has a client in that case as well — along with other aspects of Google’s business.

“It’s not going to go away quickly,” Reback said. “I think the bigger question is: Are antitrust lawyers from Silicon Valley ever going to go to Washington again?”

Reback’s long-running fight with Google has several curious twists. The firm Reback was with when he fought Microsoft, Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, now works for Google. Microsoft is now cheering and at times aiding his effort. Years ago, Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman, played an important role in explaining Reback’s case against Microsoft to the government.

Today, Reback is less of a trailblazer than he was in the Microsoft case in the United States. Indeed, he is one among the dozens of lawyers pursuing cases against Google in Europe.

The reason behind the venue change depends on where you stand. People in Google’s corner believe European technology companies, having been outflanked by U.S. competitors, want Europe’s policymakers to give them a leg up. Reback’s assessment is that U.S. regulators are afraid to confront large technology companies like Google that have become politically powerful and big D.C. donors.

Lawyers who know Reback say he can be prone to over-the-top pronunciations that seem to suggest that nothing short of the future of the technology industry rests on Europe’s producing a tough judgment on Google. Asked about this, Reback is unapologetic.

“Are you supposed to represent the client and try to get something changed, or are you supposed to just sit there?” he said in a recent interview. “I’ve never been able to just sit there.”

Reback, is 66 and has gray hair and wears glasses. If you met him at a party and he told you that he was a lawyer, this would not seem surprising.

He grew up in Tennessee and went to Yale before heading to Silicon Valley by way of Stanford Law School. After a brief stint on the East Coast, he returned to Northern California and became enamored with startup cultures. He represented Apple in 1981, when it was still a young company, and recalled that his first meeting with its co-founder, Steve Jobs, happened to fall on Halloween.

“I go down to Apple and I’m wearing a suit — I’m sure they thought I was wearing a costume — and then the Grim Reaper escorts me to the conference room,” he said.

Reback helped develop the practice of representing what antitrust lawyers call “third-party complainants.” Put simply, companies pay him to complain to the government about their larger competitors in hopes that it will provoke the antitrust authorities to do things like scuttle merger proposals or sue for abusive behavior.

“If there were intellectual-property rights for creating this niche, everyone would be paying Gary royalties,” said William E. Kovacic, a law professor at George Washington University.

The main hurdle to this approach is that when a lawyer like Reback complains, regulators are inclined to believe the clients are whiners who cannot compete. Convincing them otherwise requires detailed economic analyses, which is where Reback’s claim to legal fame comes from.

In the 1990s, he and a colleague, Susan Creighton — a Wilson Sonsini partner who now represents Google — wrote a white paper that advanced a novel economic theory on “network effects.” The paper was one of a number of complaints about Microsoft, but it has gone down in legal lore for pushing the Justice Department to investigate the software giant for antitrust violations.

The central idea in the paper was that technology, more than any other industry, tends to favor the largest competitor because the “network” is itself a competitive advantage. That is, users have to use the same thing everyone else is using. What this means, Reback said, is that in tech, antitrust law must be enforced more swiftly.

“The more you have, the more you get,” he explained.

A more recent project, produced in 2013, was a 62-page analysis of Google’s behavior in Europe. It argues that the company is deliberately trying to push comparison-shopping sites lower in its search results, not so much because it wants to take business from them, but because it doesn’t want comparison-shopping prices to show up near product ads. If that happened, consumers might be reluctant to click on those ads, he argued, and clicks are how Google is paid.

Google’s overall counterargument in Europe is that the facts do not show harm to its competitors. Shopping services are growing and many consumers, especially those on mobile phones, go straight to their merchants of choice instead of searching with Google. “These kinds of developments reflect a dynamic and competitive industry,” Kent Walker, Google’s general counsel, wrote in a blog post.

There is a common wisdom in Silicon Valley that the industry’s health relies on upstarts’ unseating their larger competitors. Reback shares it, and that is what he is trying to protect.

“If you believe in the startup culture,” he said, “there has to be a pathway to market for these things.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered