How 'robo-investing' is managing money for the masses

- 3 March 2015

- Business

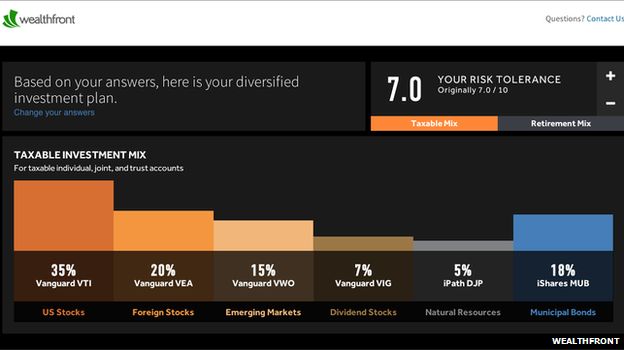

"Robo-investing" - using computer algorithms rather than humans to manage your investments - is a white-hot sector attracting lots of start-up cash.

There are now several companies here in the US promising that their algorithms can get more bang for your investment buck at a fraction of the price charged by traditional investment managers.

Managing your portfolio, diversifying your investments and handling your tax liabilities can all be done automatically 24/7.

And machines aren't swayed by fear and greed, the primary emotions that often drive very poor investment decisions. They can crunch terabytes of data and take a global, long-term view, spreading your investments across geographies and asset classes, from bonds to equities, index funds to property.

'New-fangled'

Just don't call it "robo-investing", says Adam Nash, chief executive of Wealthfront, one of the leading companies in the field, managing more than $1.8bn (£1.2bn) of client assets.

"I've never actually heard a young person refer to robo-investing since I've been here." He joined Wealthfront in 2013.

"It seems to be uniformly a term used by older financial advisers to make fun of the new-fangled tech that these kids are using. Expedia is not a robo-travel agent; I don't buy movie tickets on my robot phone."

He suggests "automated investment service" instead. As a former employee of eBay, Apple and LinkedIn, who has a computer science degree from Stanford and a business degree from Harvard, he should know.

In fact, many of the people running the companies that are igniting this new generation of personal investing combine advanced software engineering skills with strong business acumen.

Inevitably, some are likely to end up as household names and on billionaire lists in the not-too-distant future if they can achieve their ambition of expanding investment to the masses.

Jon Stein, the founder and chief executive of Betterment, is another good example. Educated at Columbia Business School and Harvard, he went on to write the initial code for Betterment's website.

"We do everything from end to end," he says. "We do your statements and tax integration; we do all the ACH [Automated Clearing House] transactions; we do the accounting and record keeping.

"We are able to make that process much more efficient and optimised around trading personalised portfolios."

Betterment says 75% of its clients are under 50. At Wealthfront 60% are under 35. So far, this has mostly been a young person's game.

Perhaps that's not surprising, says Mr Nash, considering that the younger generations are much more aware of hidden fees, having seen phone, cable, airline and brokerage companies adopting such "revenue optimisation" models.

Quite simply, many customers regard these hidden fees as stealing, he says.

"Young people hate the idea of... eight pages of fees that you don't find out about until you are already in the system.

"At Wealthfront we have literally two price points. Under $10,000 is free with no commissions at all, and over $10,000 we charge one quarter of one per cent. It's not like the millionaires are getting a better deal."

Index investing

The democratisation of high-quality investment performance is not necessarily new.

Low-fee index tracker funds attempt to replicate the performance of particular stock market indexes by copying in full, or in part, the constituent stocks making up that index. If the constituents of the index change, so will your tracker fund - automatically.

These tracker funds have produced better returns than almost any human-run fund, net of fees. And that's been proven over decades.

The Vanguard Group and its founder John Bogle have been shouting about their not-so-secret sauce for decades.

Vanguard spokeswoman Kate Henderson says the general advice for any kind of investment methodology, no matter how old or new, is the same.

"You need to do your homework no matter if you're working with an adviser face to face or a robo-adviser," she says.

"Check credentials and references, look at the financial disclosures. Understand where the fees are coming from. Ask the right questions. How is the adviser compensated?"

Low-fee advice

Vanguard says it has no plans to develop its own fully automated investment platform because its clients are generally older and have more complex portfolios. Such seasoned investors often need a helping human hand when retirement is looming.

But to fend off competition from new generation investment companies it introduced Personal Advisor Services in 2013, which offers low-fee advice and tries to mimic what "robo-investors" do.

Not that Vanguard has any reason to worry.

Many of the new automated services buy Vanguard ETF [Exchange Traded Fund] Index products as a core investment within their own portfolios. So Vanguard still dominates the industry, alongside the likes of Fidelity and Schwab.

But Wealthfront chief Adam Nash points out there is a huge difference between knowing what you're supposed to do and actually doing it consistently.

Only those with the ability, time and willingness to supervise their investments actively would find Wealthfront redundant, which is a tiny percentage of everyday investors, he believes.

'Exceptionally tarnished'

So he has no qualms about being a relative newcomer to the industry.

"You are talking about 90 million millennials [people coming of age at the turn of the 21st Century] in America. Those businesses with a gold standard are not as shiny as they used to be after the [2008] financial crises.

"I don't think you'll find any survey of millennials that puts the brand of any brokerage or bank particularly high these days. Most of the brands that took decades or even centuries to build are exceptionally tarnished with young people. We are at a unique moment."

When Jon Stein started Betterment it was out of sheer frustration with his existing brokerage firms who made it complicated to sign up and difficult to navigate through their services.

These were financial businesses first and web entities second, he argues. That's why Betterment put a lot of effort into making its website simple to use.

"We have optimised that interface and we know that it helps people stay the course," says Mr Stein.

"They make better decisions. For example, we launched a new feature called Tax Impact Preview, which tells you what your taxes will be before you make a transaction. We found that when people see this, 62% of them don't go through with the transaction."

That suggests that across the sector an awful lot of people are transacting without knowing the full implications of their choices.

Inflexible code?

But the strength of the automated investment idea is also its biggest potential weakness.

Computers and algorithms can keep you on track as long as they know the track you are on. Deviate from it in any way - a divorce, a new baby - without telling the computer and suddenly your money may be going in a different direction to you.

But for an industry still in its infancy the concept is attracting a lot of attention from venture capitalists and consumers.

Eventually every financial transaction we make is likely to be monitored in real time with instant advice available at every moment.

A frightening or wonderful thought?

- Is your digital double a thief?

- 'Phone farmers' reaping the benefits

- Self-driving cars are a distant prospect

- What is the point of Twitter?

- How gaming can make the world safer

- Fitness tech at work: friend or foe?

- Man City's vision of the future

- Website turns free time into money

- Africa's video game makers dreaming big

- Indiana Joneses in hi-tech race against Islamic State

Business

China's inflation rise misses target

- 9 August 2015

- Business

Scotland to ban GM crop growing

- 9 August 2015

- Scotland politics

Oxfam's annual income tops £401m

- 3 hours ago

- Business

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered