Business Improvement Districts Are More Than Just a Name on a Trash Can

(Photo by Oscar Perry Abello)

You see the names at every street corner. They’re usually on the trashcans. In New York, there’s the Times Square Alliance. Baltimore has the Downtown Partnership. There’s the Golden Triangle in Washington, D.C. Business improvement districts, or BIDs for short, are sort of like the urban equivalent to a mall: “Tenants” pay into a centralized organization that takes care of things like maintenance, safety, amenities and, of course, trash.

There are now over 1,000 BIDs in the U.S. alone, and New York counts 72, including 39 in low- to moderate-income neighborhoods. Walk up Broadway in Manhattan, and you’ll come across at least eight different BID trash cans, from the luxurious art-deco 34th Street Partnership receptacles to the Washington Heights BID-stamped trash bags. But the inequalities don’t end there.

Since their budgets are tied directly to property values, BIDs are all over the map financially. In New York City, they range from the Financial District’s $17.1 million Alliance for Downtown NY to the $49,740 180th Street BID in Queens, according to the FY2014 Annual BID Report from New York City’s Department of Small Business Services.

So when the New York City Council recently announced $1.25 million in supplemental funding for council members to support BIDs in their districts, it’s curious that each council member had the same funding cap — $24,000 to dole out. Jennifer Brown, executive director of the $2.2 million budget Flatiron-23rd Street Partnership, flat-out told Crain’s New York that they aren’t planning to pursue any of the supplemental funding for which they’re eligible.

Which begs the question, why not direct the supplemental BID funding to the 39BIDs in low- to moderate-income neighborhoods? But, more broadly, how effective are BIDs at supporting entrepreneurs from low-income communities?

As usual when it comes to whether a broadly supported policy helps those who are most disadvantaged, data are hard to find. But a 2007 NYU Furman Centerbriefing did note that large, wealthy BIDs in New York City do have a significant impact on commercial property values and quality of life, while smaller BIDS had a negligible impact. The study speculates that perhaps there is a certain minimum level of resources below which BIDs do not deliver a net-positive impact on their catchment area.

That said, as more resources go toward BIDs, what is it that might be useful to position them as positive forces for communities, particularly low- to moderate-income communities?

“BIDs, done right, can do a lot,” says Michael Hendrix, director for emerging issues and research at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, a sort of think tank housed inside perhaps the country’s most prominent business organization.

Success, according to Hendrix, starts with tapping into the existing momentum of a community.

“Picking up on what was already happening and asking how to support that — that helps a lot, to the point where business development starts to happen naturally, and entrepreneurs don’t even realize why they end up where they end up in cities,” says Hendrix. He has has spent the last year or so traveling the country speaking with local leaders and entrepreneurs about what makes entrepreneurial ecosystems work. (You can dig deeper into his findings in the “Innovation That Matters” report, produced in partnership with D.C. tech incubator 1776.)

“When leaders of a city want to foster entrepreneurial ecosystems, sometimes they focus on place, as in let’s build new things, let’s just focus on amenities, let’s create these place-based expenditures, or they assume that by having enough smart people and enough capital that the rest will work itself out,” Hendrix adds. “Often what you find is that cities that have become successful at creating these ecosystems, they actually lack a good degree of capital or talent, but what is there, is highly networked and efficiently used within a cohesive, open, dynamic community. BIDs can contribute to that.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Oscar is a Next City 2015-2016 equitable cities fellow. A New York City-based journalist with a background in global development and social enterprise, he has written about impact investing, microfinance, fair trade, entrepreneurship and more for publications such as Fast Company and NextBillion.net. He has a B.A. in Economics from Villanova University.

Starbucks, CVS and Friends Aim to Put 100,000 Young People to Work

Starbucks is a 100,000 Opportunities Initiative coalition member and funder. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

Despite ongoing economic recovery since the Great Recession, youth unemployment is a lingering reality for millions. Summer employment alone has plummeted since the late ’90s for teenagers, and initiatives in cities from San Jose, California, to Madison, Wisconsin, seek to combat the problem.

This week, a big boost arrived from the private sector. The new 100,000 Opportunities Initiative is a national coalition of U.S.-based companies committed to hiring at least 100,000 youths by 2018. Companies include CVS, FedEx, Starbucks, Microsoft and Sweetgreen. The goal’s breakdown: to place young Americans, ages 16 to 24, in apprenticeships, internships, training programs and both part-time and full-time jobs.

The program officially kicks off next week in Chicago at a job fair where participating companies — and an expected 2,000 youths — will mingle, with around 200 on-the-spot job offers on the table.

“Bringing this first hiring fair to Chicago will have an impact on both the businesses and the young people that they will hire for years to come, supporting growth in the city’s economy and creating more opportunities for our residents,” Mayor Rahm Emanuel said. “Chicago will have the chance to showcase its talented workforce to the participating companies and further increase the potential of our residents to secure lasting employment.”

The initiative has received funding support from both the private and philanthropic spheres, including the Rockefeller Foundation (which also provides funding support to Next City) and the Schultz Family Foundation.

“We know that this is a complex issue and we need all of our collective horsepower to solve it,” said Sheri Schultz, of the Schultz Family Foundation. “For too long, it’s been the nonprofit and public sectors tackling this issue, without meaningful involvement from the private sector. Closing the opportunity divide requires bold leadership and innovation across all sectors.”

Marielle Mondon is an editor and freelance journalist in Philadelphia. Her work has appeared inPhiladelphia City Paper, Wild Magazine, and PolicyMic. She previously reported on communities in Northern Manhattan while earning an M.S. in journalism from Columbia University.

Texas Tinkerer “Takes Apart” Surface Transportation

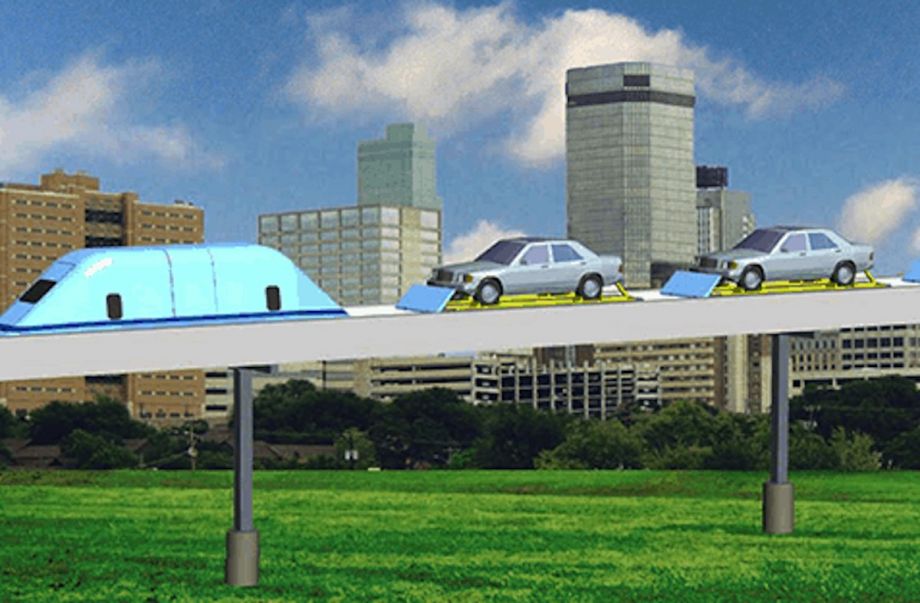

ROAM’s MegaWay commuter service (Credit: ROAM Transport Systems)

The big obstacle to getting public buy-in on rail transit is the fact that the public will be paying for it for as long as it runs. Only in the densely packed cities of Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong do rail mass transit systems turn a profit on operations, and of those, only one — Hong Kong’s Mass Transit Railway (MTR) — makes a profit large enough to cover the entire cost of capital improvements and extensions. That’s due in part to Hong Kong’s high population density, in part to its low rate of car ownership (a function of that density), and in part because theMTR also makes money as a landlord of properties around its stations.

Few Americans would want to live at Hong Kong, Singapore or Tokyo densities, so the Hong Kong approach to profitable rail transit is out of reach in the United States, even if “value capture” were to become more widespread. But there is someone out there who has been hard at work coming up with a rail transit technology that can pay for itself, even in an American context.

Kirston Henderson, an engineer in Fort Worth, Texas, is the founder and CEO of ROAM Transport Systems, a company that has developed a modular fixed-guideway transit system. Henderson says it can be built with minimal public funds and can cover its own operating and maintenance costs out of fare revenues.

The system, which comes in small-, medium- and large-capacity versions, is an elevated rail transit system he developed in order to solve two problems he saw in transporting goods and people: the high cost of building urban freeways and the higher cost of building urban rail.

By his own description, Henderson is an inveterate tinkerer, a product of his education and career choice.

“I have a master of science in physics, which makes you a jack of all trades in the engineering field,” he says. In systems engineering, that means “you take a problem and figure out a better way to solve it.” He also holds 15 patents representing some 100 unique claims, the fruit of all that tinkering.

“One of the things I decided I needed to take apart and find a better answer for was the issue of surface transportation, both rail and bus.”

The problem, as he saw it, was that both fast highways and fast trains were too costly and inefficient. Much of the cost of a freeway goes into laying down concrete that tires will almost never actually touch, while rail transit systems all require subsidies to build and run.

“I analyzed the problem and came up with a number of requirements. It had to be able to climb hills in all weather” — something no steel-wheel technology can do. “It needed to move cargo, to provide point-to-point transportation for people in their individual cars, and it needed to provide both local transportation and high-speed intercity transportation.

“The other problem was that it had to be affordable” — less than the cost not only of a mile of light rail or subway, but also the cost of a mile of urban freeway.

The solution he developed is a cousin of the rubber-tired metro technology developed in France and found on subways in Paris, Mexico City and Montreal. The difference is that Henderson’s system is essentially two one-tire-wide highways enclosed in box culverts. The rubber-tired modular cars touch only the metal strips in the bottom of the culvert, which also contains the power supply and guidance system. The “tracks” are mounted on support pillars to form an elevated rail line.

The vehicles carry either passengers, goods or cars that would drive onto flatcar platforms and would operate automatically, with no drivers. Henderson envisions them operating autonomously rather than in trains.

Henderson claims that his “MegaWay” system, designed for urban transit applications, costs 20 to 25 percent of a light-rail line.

“The cost of the guideway, the power supply system and the initial complement of vehicles is about $10 million per mile,” a figure he arrived at based on bids he submitted to some urban transit agencies. By comparison, a lane mile of Interstate highway costs $16 million and a typical light-rail or intercity high-speed rail line costs around $100 million a mile.

“We want to price this system in a range where cities can build it with their own money.”

So far, there have been no takers, but testing of the system continues at the company’s facility in Texas.

Philadelphia freelance writer Sandy Smith runs the Philly Living Blog for Noah Ostroff & Associates, a Philadelphia real estate brokerage. A veteran journalist with nearly 40 years’ experience, Smith writes extensively on transportation, development and urban issues for several media outlets, including Philadelphiamagazine online.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered