Alan Bennett

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other people named Alan Bennett, see Alan Bennett (disambiguation).

| Alan Bennett | |

|---|---|

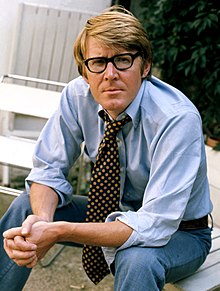

Bennett in 1973, photographed by Allan Warren

| |

| Born | 9 May 1934 Armley, Leeds, England |

| Occupation | Actor, author |

| Years active | 1960–present |

| Partner(s) | Rupert Thomas |

Alan Bennett (born 9 May 1934) is an English playwright, screenwriter, actor and author. He was born in Leeds and attended Oxford University where he studied history and performed with the Oxford Revue. He stayed to teach and research medieval history at the university for several years. His collaboration as writer and performer with Dudley Moore, Jonathan Miller and Peter Cook in the satirical revue Beyond the Fringe at the 1960 Edinburgh Festival brought him instant fame. He gave up academia, and turned to writing full-time, his first stage play Forty Years On being produced in 1968.

His work includes The Madness of George III and its film adaptation, the series of monologues Talking Heads, the play and subsequent film The History Boys, and popular audio books, including his readings of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Winnie-the-Pooh.

Contents

[hide]Early life[edit]

Bennett was born in Armley in Leeds.[1] The son of a co-op butcher, Walter, and his wife Lilian Mary (née Peel), Bennett attended Christ Church, Upper Armley, Church of England School (in the same class as Barbara Taylor Bradford), and then Leeds Modern School (now Lawnswood School). He learned Russian at the Joint Services School for Linguists during his national service before applying for a scholarship at Oxford University. He was accepted by Exeter College, Oxford, from which he graduated with a first-class degree in history. While at Oxford he performed comedy with a number of eventually successful actors in the Oxford Revue. He was to remain at the university for several years, where he researched and taught Medieval History, before deciding he was not cut out to be an academic.

Career[edit]

In August 1960 Bennett, along with Dudley Moore, Jonathan Miller and Peter Cook, achieved instant fame by appearing at the Edinburgh Festival in the satirical revue Beyond the Fringe. After the festival, the show continued in London and New York. He also appeared in My Father Knew Lloyd George. His highly regarded television comedy sketch series On the Margin (1966) was unfortunately erased; the BBC re-used expensive videotape rather than keep it in the archives. However, in 2014 it was announced that copies of the entire series had been found.

Around this time Bennett often found himself playing vicars and claims that as an adolescent he assumed he would grow up to be a Church of England clergyman, for no better reason than that he looked like one.

Bennett's first stage play Forty Years On, directed by Patrick Garland, was produced in 1968. Many television, stage and radio plays followed, with screenplays, short stories, novellas, a large body of non-fictional prose, and broadcasting and many appearances as an actor.

Bennett's distinctive, expressive voice (which bears a strong Leeds accent) and the sharp humour and evident humanity of his writing have made his readings of his work very popular, especially the autobiographical writings. Bennett's readings of the Winnie the Pooh stories are also widely enjoyed.

Many of Bennett's characters are unfortunate and downtrodden. Life has brought them to an impasse or else passed them by. In many cases they have met with disappointment in the realm of sex and intimate relationships, largely through tentativeness and a failure to connect with others.

Despite a long history with both the National Theatre and the BBC - Bennett never writes on commission, declaring "I don't work on commission, I just do it on spec. If people don't want it then it's too bad."[2]

Bennett is both unsparing and compassionate in laying bare his characters' frailties. This can be seen in his television plays for LWT from the early 1970s through to his work for the BBC in the early 1980s. His many works for television include his first play for the medium, A Day Out in 1972, A Little Outing in 1977, Intensive Care in 1982, An Englishman Abroad in 1983, and A Question for Attribution in 1991.[3] But his perhaps most famous screen work is the 1987 Talking Heads series of monologues for television which were later performed at the Comedy Theatre in London in 1992. This was a sextet of poignantly comic pieces, each depicting several stages in the character's decline from an initial state of denial or ignorance of their predicament, through a slow realisation of the hopelessness of their situation, progressing to a bleak or ambiguous conclusion. A second set of six Talking Heads followed a decade later, which was darker and more disturbing.

In his 2005 prose collection Untold Stories Bennett has written candidly and movingly of the mental illness that his mother and other family members suffered. Much of his work draws on his Leeds background and while he is celebrated for his acute observations of a particular type of northern speech ("It'll take more than Dairy Box to banish memories of Pearl Harbour"), the range and daring of his work is often undervalued. His television play The Old Crowd includes shots of the director and technical crew, while his stage play The Lady in the Van includes two characters named Alan Bennett.

The Lady in the Van was based on his experiences with a tramp called Miss Shepherd, who lived on Bennett's driveway in several dilapidated vans for more than fifteen years. A radio play of the same title was broadcast on 21 February 2009 on BBC Radio 4, with actress Maggie Smith reprising her role of Miss Shepherd and Alan Bennett playing himself. The work has also been published in book form. Alan Bennett adapted The Lady in the Van for the stage.

Bennett adapted his 1991 play The Madness of George III for the cinema. Entitled The Madness of King George (1994), the film received four Academy Award nominations: for Bennett's writing and the performances of Nigel Hawthorne and Helen Mirren. It won the award for best art direction.

Bennett's critically acclaimed The History Boys won three Laurence Olivier Awards in 2005, for Best New Play, Best Actor (Richard Griffiths), and Best Direction (Nicholas Hytner), having previously won Critics' Circle Theatre Awards and Evening Standard Awards for Best Actor and Best Play. Bennett also received the Laurence Olivier Award for Outstanding Contribution to British Theatre.[4] The History Boys won six Tony Awards on Broadway, including best play, best performance by a leading actor in a play (Richard Griffiths), best performance by a featured actress in a play (Frances de la Tour), and best direction of a play (Nicholas Hytner). A film version of The History Boys was released in the UK in October 2006.

Bennett wrote the play Enjoy in 1980. It was one of the rare flops in his career and barely scraped a run of seven weeks at the Vaudeville Theatre, in spite of the stellar cast of Joan Plowright, Colin Blakely, Susan Littler, Philip Sayer, Liz Smith (who replaced Joan Hickson during rehearsals) and, in his first West End role, Marc Sinden. It was directed by Ronald Eyre.[5] A new production of Enjoy attracted very favourable notices during its 2008 UK tour[6] and moved to the West End of London in January 2009.[7] The West End show took over £1m in advance ticket sales[8] and even extended the run to cope with demand.[9] The production starred Alison Steadman, David Troughton, Richard Glaves, Carol Macready and Josie Walker.

At the National Theatre in late 2009 Nicholas Hytner directed Bennett's play The Habit of Art, about the relationship between the poet W.H. Auden and the composer Benjamin Britten.[10]

Bennett's new play People opened at the National Theatre in October 2012.[11]

Personal life[edit]

In September 2005, Bennett revealed that, in 1997, he had undergone treatment for cancer, and described the illness as a "bore". His chances of survival were given as being "much less" than 50%.[12] He began Untold Stories (published 2005) thinking it would be published posthumously, but his cancer went into remission. In the autobiographical sketches which form a large part of the book Bennett writes openly for the first time about his homosexuality (Bennett has had relationships with women as well, although this is only touched upon in Untold Stories). Previously Bennett had referred to questions about his sexuality as like asking a man who has just crawled across the Sahara desert to choose between Perrier or Malvern mineral water.[13]

Bennett lives in Camden Town in London, and shares his home with Rupert Thomas, the editor of World of Interiors magazine.[14] Bennett also had a long-term relationship with his former housekeeper, Anne Davies, until her death in 2009.[15]

In 2010, Bennett described how he was mugged by two women who surreptitiously squirted him with ice cream in Marks & Spencer, Camden Town. As they purported to wipe off the confection with tissues, the robbers stole £1,500 cash he had withdrawn from the bank minutes earlier. Bennett, who initially was grateful the women had helped clean him, said the experience afterwards made him 'less likely to believe in the kindness of strangers'.[16]

Bennett is a lapsed Anglican; raised in the church, he became very religious as a teenager, but has "slowly left it [The Church] over the years," though he still holds a faith, and is often supportive of the restoration of churches through Britain.[17]

Archive[edit]

In October 2008 Bennett announced that he was donating his entire archive of working papers, unpublished manuscripts, diaries and books to the Bodleian Library, stating that it was a gesture of thanks repaying a debt he felt he owed to the British welfare state that had given him educational opportunities which his humble family background would otherwise never have afforded.[18]

Depictions[edit]

- In the film for television Not Only But Always about the careers of Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, Alan Cox played Alan Bennett.

- Along with the other members of Beyond the Fringe, Bennett is portrayed in the play Pete and Dud: Come Again, by Chris Bartlett and Nick Awde.

- Bennett voices himself in the episode Brian's Play of the animated series Family Guy.

- Bennett was portrayed by Harry Enfield as Stalin, in an episode of "Talking Heads of State", in BBC Two's satirical Harry and Paul's Story of the Twos, broadcast in May 2014.[19]

- Bennett was portrayed by Reece Dinsdale in a production of Untold Stories at the West Yorkshire Playhouse in June 2014.[20]

- Bennett will be portrayed by British actor Alex Jennings in the upcoming 2015 film The Lady in the Van.

Work[edit]

Television[edit]

|

|

Stage[edit]

| Film[edit]

Radio[edit]

|

Books[edit]

- Beyond the Fringe (with Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller, and Dudley Moore). London: Souvenir Press, 1962, and New York: Random House, 1963

- Forty Years On, London: Faber, 1969

- Getting On, London: Faber, 1972

- Habeas Corpus, London: Faber, 1973

- The Old Country, London: Faber, 1978

- Enjoy, London: Faber, 1980

- Office Suite, London: Faber, 1981

- Objects of Affection, London: BBC Publications, 1982

- A Private Function, London: Faber, 1984

- Forty Years On; Getting On; Habeas Corpus, London: Faber, 1985

- The Writer in Disguise, London: Faber, 1985

- Prick Up Your Ears: The Film Screenplay, London: Faber, 1987

- Two Kafka Plays, London: Faber, 1987

- Talking Heads, London: BBC Publications, 1988; New York: Summit, 1990

- Single Spies, London: Faber, 1989

- Single Spies and Talking Heads, New York: Summit, 1990

- The Lady in the Van, 1989

- Poetry in Motion, (with others). 1990

- The Wind in the Willows, London: Faber, 1991

- Forty Years On and Other Plays, London: Faber, 1991

- The Madness of George III, London: Faber, 1992

- Poetry in Motion 2 (with others) 1992

- Writing Home (memoir & essays) London: Faber, 1994

- The Madness of King George (screenplay), 1995

- Father ! Father ! Burning Bright (prose version of 1982 TV script, Intensive Care), 1999

- The Laying on of Hands (stories), 2000

- The Clothes They Stood Up In (novella), 2001

- Untold Stories (autobiographical and essays), London, 2005, ISBN 0-571-22830-5

- The Uncommon Reader (novella), London, 2007

- A Life Like Other People's (memoir), London, 2009

- Smut: two unseemly stories (stories), London, 2011

Audio releases[edit]

|

|

Awards and honours[edit]

Awards[edit]

- 1963 Tony Award, Special Award: Beyond the Fringe (shared with Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller and Dudley Moore)

- 1963 New York Drama Critics' Circle Award, Special Award: Beyond the Fringe (shared with Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller and Dudley Moore)

- 1968 Evening Standard Award, Special Award: Forty Years On

- 1985 Evening Standard British Film Award, Best Screenplay: A Private Function (shared with Malcolm Mowbray)

- 1987 Critics' Circle Film Award, Screenwriter of the Year: Prick Up Your Ears

- 1987 Evening Standard British Film Award, Best Screenplay: Prick Up Your Ears

- 1989 Hawthornden Prize: Talking Heads

- 1990 Laurence Olivier Award, Best New Comedy: Single Spies

- 1992 British Academy Television Award, Best Single Drama: A Question of Attribution

- 1992 Laurence Olivier Award, Best Entertainment: Talking Heads

- 1992 Laurence Olivier Award, Best Actor in a Musical: Talking Heads

- 1995 Critics' Circle Film Award, Screenwriter of the Year: The Madness of King George

- 1995 Evening Standard British Film Award, Best Screenplay: The Madness of King George

- 1995 British Book Award, Book of the Year: Writing Home

- 1996 British Academy Film Award, Alexander Korda Award for Best British Film: The Madness of King George

- 2000 British Comedy Award, Lifetime Achievement Award

- 2002 British Book Award, Audiobook of the Year: The Laying on of Hands

- 2003 New York Drama Critics' Circle Award, Best Foreign Play: Talking Heads

- 2003 British Book Award, Lifetime Achievement Award

- 2004 Critics' Circle Theatre Award, Best New Play: The History Boys

- 2004 Evening Standard Award, Best Play: The History Boys

- 2005 Laurence Olivier Award, Best New Play: The History Boys

- 2005 Laurence Olivier Award, Society of London Theatre Special Award

- 2005 Critics' Circle Award for Distinguished Service to the Arts

- 2006 Drama Desk Award, Outstanding Play: The History Boys

- 2006 New York Drama Critics' Circle Award, Best Play: The History Boys

- 2006 Outer Critics Circle Award, Outstanding Broadway Play: The History Boys

- 2006 Tony Award, Best Play: The History Boys

- 2006 J. R. Ackerley Prize for Autobiography: Untold Stories

- 2006 British Book Award, Author of the Year

- 2008 Bodley Medal

Nominations[edit]

- 1984 British Academy Film Award, Best Original Screenplay: A Private Function

- 1987 British Academy Film Award, Best Adapted Screenplay: Prick Up Your Ears

- 1989 British Academy Television Award, Best Actor: A Chip in the Sugar

- 1989 British Academy Television Award, Best Drama Series: A Cream Cracker under the Settee (shared with Innes Lloyd)

- 1989 British Academy Television Award, Best Single Drama: A Bed Among the Lentils (shared with Innes Lloyd)

- 1989 British Academy Television Award, Best Single Drama: A Lady of Letters (shared with Innes Lloyd and Giles Foster)

- 1994 Academy Award, Best Adapted Screenplay: The Madness of King George

- 1995 British Academy Film Award, Best Adapted Screenplay: The Madness of King George

- 1999 British Academy Television Award, Best Single Drama: Waiting for the Telegram (shared with Mark Shivas and Stuart Burge)

- 1999 British Academy Television Award, Best Single Drama: Playing Sandwiches (shared with Mark Shivas and Udayan Prasad)

- 2003 Drama Desk Award, Outstanding Play: Talking Heads

- 2003 Outer Critics Circle Award, Outstanding Off-Broadway Play: Talking Heads

- 2006 Samuel Johnson Prize: Untold Stories

- 2007 GLAAD Media Award, Outstanding Film - Limited Release: The History Boys

- 2008 Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize: The Uncommon Reader

Bennett was made an Honorary Fellow of Exeter College, Oxford, in 1987. He was also awarded a D.Litt by the University of Leeds in 1990[22] and an honorary doctorate from Kingston University in 1996. In 1998 he refused an honorary doctorate from Oxford University, in protest at its acceptance of funding for a chair from press baron Rupert Murdoch.[23] He also declined a CBE in 1988 and a knighthood in 1996.[24] He has stated that, although he is not a republican, he would never wish to be knighted, saying it would be a bit like having to wear a suit for the rest of his life.[25] Bennett earned Honorary Membership of The Coterie in the 2007 membership list.

In December 2011 Bennett returned to Lawnswood School, nearly 60 years after he left, to unveil the renamed Alan Bennett Library.[26] He said he "loosely" based The History Boys on his experiences at the school and his admission to Oxford. Lawnswood School dedicated its library to the writer after he emerged as a vocal campaigner against public library cuts.[27] Plans to shut local libraries were "wrong and very short-sighted", Bennett said, adding: "We're impoverishing young people."

References[edit]

- ^ Bennett, Alan (2014). "Fair Play". London Review of Books 36 (12): 29–30. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0003141/bio?ref_=nm_dyk_qt_sm#quotes

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0003141/

- ^ Jury, Louise."Historic night for Alan Bennett as his new play dominates the Olivier awards", The Independent, 21 February 2005

- ^ Shenton, Mark."Which flops are ripe for revival?" Theatre Blog, guardian.co.uk, 28 August 2008

- ^ Let's enjoy Alan Bennett's revival play for what it is – Daniel Tapper on Alan Bennett's Enjoy guardian.co.uk, 6 February 2009

- ^ Enjoy by Alan Bennett at the Gielgud Theatre, review Telegraph, 3 February 2009

- ^ Curtain re-opens on Bennett Play BBC News, 29 January 2009

- ^ Bennett's Enjoy extends two weeks to 16 May 2009 London Theatre, 18 February 2009

- ^ "Nicholas Hytner on his time at the National Theatre", Times Online, 9 February 2009

- ^ "Alan Bennett's new play to open at National Theatre", The Guardian, 23 January 2012

- ^ "Alan Bennett reveals cancer fight", BBC News, 24 September 2005

- ^ "Inside Bennett's fridge", Telegraph, 30 October 2004

- ^ The Guardian profile: Alan Bennett The Guardian,_14_May 2004

- ^ Alan Bennett reveals that his lover, 'Café Anne', is dead The Independent, 22 November 2009

- ^ Cable, Simon (13 December 2010). How two women 'well-wishers' conned Sir Alan Bennett out of £1,500 in 'Mustard Squirter' scam, Daily Mail, Retrieved 8 September 2013

- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ Kennedy, Maev "A small way of saying thank you: Bennett donates his life's work to the Bodleian", The Guardian, 24 October 2008

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://www.wyp.org.uk/what's-on/2014/untold-stories/

- ^ "Alan Bennett contemporary Hamlet 'Denmark Hill' heading for Radio 4". Radio Times. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ An evening with Alan Bennett University of Leeds, 29 October 2007

- ^ "Bennett snubs Oxford over Murdoch chair", BBC News, 15 January 1999

- ^ "Birthday boy" – Blake Morrison salutes Alan Bennett as the writer approaches his 75th birthday The Guardian, 7 May 2009

- ^ Featured interview: Alan Bennett In Conversation Front Row archive, BBC Radio 4 (Audio, 1 hr)

- ^ 'Alan Bennett: Playwright returns to Leeds school' (Video, 2 mins) Yorkshire Evening Post

- ^ "Alan Bennett warns over tuition fees" at BBC News, Entertainment & Arts

Further reading[edit]

- Peter Wolfe, Understanding Alan Bennett, University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 1-57003-280-7

- Alexander Games (2001). Backing Into The Limelight: The Biography of Alan Bennett. Headline. ISBN 0-7472-7030-9.

- Joseph H. O'Mealy, Alan Bennett: A Critical Introduction, Routledge, 2001, ISBN 0-8153-3540-7

- Kara McKechnie, Alan Bennett, The Television Series, Manchester University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7190-6806-5

- Robert Hewison Footlights – A Hundred Years of Cambridge Comedy, Methuen, 1983

- Roger Wilmut From Fringe to Flying Circus – Celebrating a Unique Generation of Comedy 1960–1980, Eyre Methuen, 1980

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Alan Bennett |

- Profile at the British Council

- Interview BBC archive 6 December 2009 with Mark Lawson. (Video, 1 hr)

- BBC Interview Radio 4 Front Row archive. (Audio, 1 hr)

- Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery (3 pages)

- [2] IMDB listing

- "Curtain re-opens on Bennett play" BBC News, 29 January 2009 – Video interview with Alan Bennett

- Profile. British Film Institute: Screenonline

- Guardian profile "Birthday boy" 7 May 2009 by Blake Morrison.

- Alan Bennett Macmillan Books

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

Categories:

- 1934 births

- Living people

- Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford

- Audio book narrators

- BAFTA winners (people)

- Cancer survivors

- English Anglicans

- English diarists

- English dramatists and playwrights

- English male radio actors

- English memoirists

- English radio personalities

- English satirists

- English screenwriters

- English male stage actors

- English television writers

- Fellows of Exeter College, Oxford

- Gay actors

- Gay writers

- LGBT screenwriters

- LGBT writers from England

- Male actors from Leeds

- Laurence Olivier Award winners

- People from Armley

- Tony Award winners

- British Book Award winners

- People educated at Leeds Modern School

- People from Leeds

- 20th-century dramatists and playwrights

- 21st-century dramatists and playwrights

- LGBT dramatists and playwrights

- English male writers

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered