Busting 3 Myths About Public Housing

A wrecking ball tears at one of several Cabrini Green housing project buildings in Chicago in this photo from 1995. (AP Photo/Beth A. Keiser, File)

City success story? Or grim urban disaster? When it comes to the lens through which Americans view public housing, conventional wisdom heavily favors the latter. Yet new research reveals the many successes of public housing both large (New York City) and small (the thousands of small housing authorities that provide public housing without incident).

Most recently, Public Housing Myths: Perception, Reality, and Social Policy attempts to break down assumptions further about America’s most maligned safety net program in 11 essays. The three here are not necessarily the most important from the book, but they all complicate timeworn narratives.

1. Don’t Blame the High-Rises.

High-rise developments or “towers in a park” define public housing in the national imagination. These hulking structures catch the eye and often received a disproportionate share of media attention both in the halcyon early days and during the depths of the urban crisis which they came to symbolize. But even though they were often poorly integrated into their surrounding neighborhoods, these apartment towers were not inevitably plagued by trouble because of design alone.

When many cities began rapidly losing population and jobs — and began to experience rising crime — public housing suffered along with all other neighborhoods. But their troubles were often given the most media attention, and they became stereotyped as hotbeds of violence. The most famous denunciation of high-rises as criminal hotspots came from Oscar Newman’s 1973 architecture book Defensible Space — an in-depth analysis of crime in the New York City Housing Authority’s (NYCHA) complexes. “It is the apartment tower itself which is the real and final villain,” Newman concludes.

But the fate of the high-rises was largely predicated on local context, not architecture. Joseph Heathcott points out in the first Public Housing Myths essay, “Violent crime rates were no higher — and were often lower — in Pruitt-Igoe than in many of the low-rise neighborhoods on the West Side” … until the buildings began to be abandoned. (Pruitt-Igoe was a St. Louis high-rise public housing complex that was torn down in the ’70s.)

Operating costs largely came from tenant rents, so when cities lost over half their populations, vacancies often opened in public housing as well and the maintenance of the buildings suffered.

In New York, where population loss was minimal, NYCHA housing complexes actually had lower rates of crime than their surrounding neighborhoods. In Fritz Umbach and Alexander Gerould’s definitive takedown of Newman’s Defensible Space theory, they show that the numbers Newman used don’t tell the story he wanted them to. A 1999 study of NYCHA found that higher poverty rates were the principal predictor of violent crime, not height. By then, New York’s public housing was home to more violent crime than its surrounding neighborhoods, but this correlated to policy changes that ensured the population would be poorer. Other cities reported similar findings, as public housing residents in Baltimore and D.C. were often safer from violence in the 1970s, or at least equally exposed, as their counterparts in the surrounding neighborhoods. Only as public housing’s funding began to be drained away, and poorer and poorer residents moved in, did violence within the complexes begin to rise.

2. You Need a Balance Among Adults and Kids.

The other factor that Newman missed in his study is that the two NYCHA complexes he looked at had an unusually high ratio of children to adults. D. Bradford Hunt argues that such concentrations were common in public housing complexes across the nation. Teenage vandalism and petty crime is kept in check not just by official law enforcement, but by the presence of adults, so that imbalance created massive problems.

In Chicago, for example, the decision was made to chiefly cater to large families that had trouble finding housing on the private market. In the Robert Taylor Homes, 80 percent of the units had three to five bedrooms, whereas that figure in earlier complexes had been 32 percent. The result was a population of 20,000 youths to 7,000 adults, a youth density of 2.86. The youth density of all CHA’s holdings was 2.11. Compare that to the baby boom suburb of Park Forest to the south of the city — a planned community specifically created for middle-class families — where the youth density was only 0.97. “In no sizeable residential community in modern history had so many youths been supervised so few adults,” writes Hunt.

Across the nation it was common to find almost two times the number of youths as adults in family public housing complexes (in 1968 the average youth density was 1.94). High youth densities made public housing hard to govern, more expensive to maintain and less appealing places to live. They were also the result of policy decisions, however well intentioned, that were not inevitable. Part of NYCHA’s success is rooted in the fact that their youth densities averaged much closer to those of Park Forest.

3. Public Housing Residents Organize … for More Police.

Fritz Umbach’s second contribution to Public Housing Myths is meant to undermine the notion that public housing residents hate the police. He emphasizes the unique case of NYCHA’s police department, which existed from 1952 to 1995, where officers were more likely to be people of color (than was the case with their NYPD counterparts), and many actually lived in public housing. No other housing authority enjoyed an equivalent. Amid rising crime levels in the city at large, Umbach writes, “From the late 1950s until the end of the 1970s, [NYCHA] tenants’ most urgent and insistent political goal was the hiring of more Housing Police.”

Umbach’s essay employs several stories of leftist 1960s activist groups attempting to organize public housing residents only to find that what their constituents wanted was harsher eviction policies for troublemakers and a heightened housing police presence. The Puerto Rican radical group the Young Lords — which employed a lot of anti-police “pig” rhetoric — found themselves organizing a rent strike and sit-ins to demand the hiring of more officers. Such actions were successful: During the peak years of tenant activism, the ranks of the housing police grew by 60 percent.

Public housing residents in other cities couldn’t make such demands, as they didn’t have a housing police department. But stricter eviction action against unruly tenants seems to be a common demand. In Lisa Belkin’s Show Me a Hero, about public housing in Yonkers (and soon to be an HBO mini-series), a tenant group called READY presses for “a screening committee to make sure only the most responsible applicants would be allowed the privilege of living in public housing.” Such strictures also contributed to NYCHA’s longevity, as the agency struggled against becoming housing exclusively for the poorest where other authorities accepted that role and subsequently struggled.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Jake Blumgart is a contributing writer at Next City. His work also appears regularly in Al Jazeera America, the Philadelphia Inquirer and Pacific Standard.

Here’s What Happens When You Really Try to Help 40,000 Low-Income People

(AP Photo/James A. Finley)

If there were just one perfect solution to every urban problem, we could probably get away with publishing fewer words on Next City each day. Instead, smart cities — and planners and advocates and so on — tackle the challenges cities face with a pretty big toolbox.

Just last month, contributor Marielle Mondon wrote about an Urban Institute report that argued that “the most effective way to beat poverty in New York would be a combination of … programs — which could cut the overall poverty rate in the city by between 44 and 69 percent.” In the arsenal: increasing the number of housing vouchers, New York City’s earned-income tax credit, and the Paycheck Plus program.

A new self-study from LISC (LISC) underscores the payoff of a multi-pronged approach. After analyzing its own efforts to help people find financial health, the community development organization notes that low-income people have a better chance at economic stability when they access a “bundled” set services: namely, job training/placement services, public benefits and financial coaching.

The study looked at 40,000 low-income clients (of LISC’s financial opportunity centers) who received assistance with job placement, budget-setting, improving credit and saving for the future. Of those who were most engaged with the program, 74 percent were placed in jobs, 78 percent retained those jobs, and 76 percent raised their net incomes.

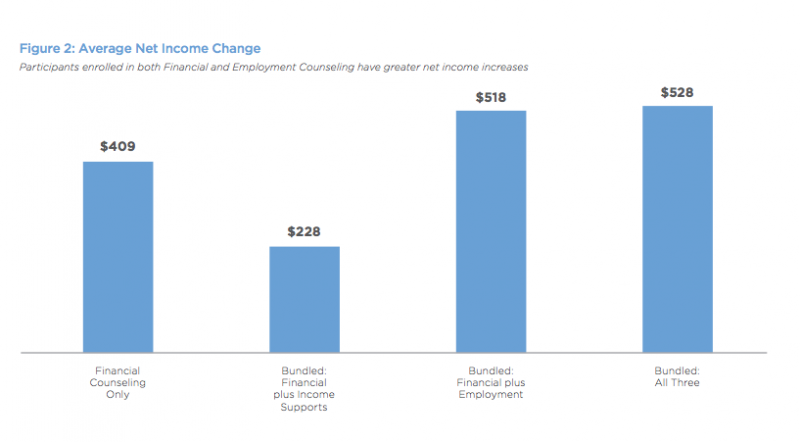

The report also breaks down how that assistance, individually and bundled, has played out in dollars and cents:

“What sets [these LISC centers] apart from traditional workforce development programs is the bundling of employment services and financial coaching — those are at its core,” Michael Rubinger, president and CEO of LISC, said in a statement. “Families that have struggled for years — and in some cases, for generations — find that they have someone in their corner, a financial coach who understands how to address their challenges and can help them change course. That can make all the difference.”

Jenn Stanley is a freelance journalist, essayist and independent producer living in Chicago. She has an M.S. from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered