Rethinking Architecture to Evade Violence

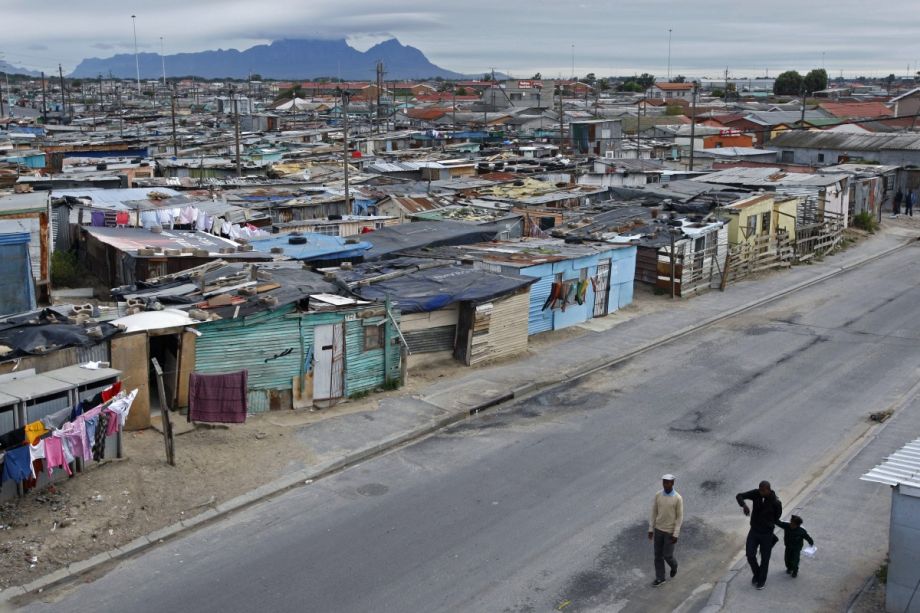

Khayelitsha township, on the outskirts of Cape Town, South Africa (AP Photo/Schalk van Zuydam)

Attempts to make “social improvements” by altering the physical structures of a community don’t always end well. A few years ago, the hit movie Slumdog Millionaire inspired a multibillion-dollar effort to overhaul Mumbai mega-slum Dharavi, the film’s setting. The revamp derailed when local residents complained that removing their homes and informal businesses was unjust. Thirty years ago in America, “broken windows theory” targeted crime reduction through crackdowns on graffiti, vandalism and other minor crimes. The concept is now linked to stop-and-frisk policing in U.S. cities, implicated in discrimination against people of color and community distrust of police.

Alastair Graham hopes Violence Prevention Through Urban Upgrading, an initiative of the government of Cape Town, South Africa, will end better. He calls the effort, which has been revamping areas around train stations since 2006, part of “a package of potential solutions … either improving safety, or improving socioeconomic situation, or improving quality of life.” The project is aimed at curbing violence by augmenting the public spaces in which violent crime frequently occurs — turning those spaces into places informal workers can conduct business.

One wouldn’t think the architecture of Khayelitsha, a black township near Cape Town, is a battleground for health. In comparison to much of the African continent, where dusty roads and mud-brick houses are typical, the area is somewhat luxurious. Shipping-container shops and tin shacks abound, but there are also paved roads, well-maintained bridges and a tidy train station. A hospital with a World Design City 2014plaque in the lobby is walking distance from a well-appointed magistrate court; next to that, a swimming pool sparkles blue in the sun.

Yet Khayelitsha is a rather ominous place. Noticing a lone white woman on the street (me — I’m currently here reporting on sexual violence under a Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting grant), locals will stop to warn of violence and robbery. The warnings are no mere paranoia. South Africa has a severe problem with violence, particularly in lower-income areas. Rapes are common. Death by shooting or “necklacing” (a practice of placing tires around the necks of a victim and burning it, and him, in front of a crowd) are also familiar, and xenophobia leads to particularly strident attacks on immigrants.

To remove the threats, Graham says the city has invested in strategic designs to improve public spaces. This includes extending a train line and providing city services to informal settlements that are otherwise deprived. It also means creating space around train stations for formal businesses and informal traders, as well as the transportation that residents need — in short, a vibrant hub where safety can be assured by the presence of crowds.

Khayelitsha’s informal workers show rather muted enthusiasm for the project. “I don’t think it’s working,” says Ola Adeyeye, a lifelong resident who sells small items near the train station. He attributes safety to leaving with all other local sellers at 6 p.m. sharp, but says, “We are struggling to survive.”

Conrad Mzukesi, who sells fruit on an overpass near the Khayelitsha Hospital, hadn’t heard of the upgrading effort, but isn’t unsure that improved urban design is the answer. “I think [the violence] is worse now,” he says, attributing the issue to “the youngsters. They are doing drugs … [and] alcohol. Alcohol abuse, I think that is the cause of the violence.”

Graham says community concerns are mainly focused around practical aspects of the project: “What portion of the investment coming to the community can we mobilize local effort into the construction … to local subcontractors?” He adds that the city-funded project “has learned a lot” and is committed to improved relations, including through smoother hires of informal construction workers.

The effort intends to include informal workers after construction is done, too, by “identifying the best places for people to do informal trade” and designing the new areas to accommodate these. VPUU’s efforts to bolster their work opportunities, in other words, mean the project is a progressive mix of large-scale construction projects and a tolerance for the smallest and weakest businesses — ones that function in cardboard shacks, or that use no building at all.

This point might be the most progressive of the project’s aims against violence. The violent milieu of South African townships is thought to suppress the informal economy, which, despite South Africa’s sky-high unemployment, represents just one-fifth of the total economy. (In contrast, informal workers make up more than half of the economies of most other African nations.) The informal sector, anthropologist Keith Hart says, is “strongly associated with African immigrants” who often cannot enter formal employment. Although these workers are not the majority of informal workers, international and national migrants (from rural South Africa) are more likely to engage in informal labor than lifelong urbanites — and perceptions that they outcompete locals has left these workers particularly vulnerable to violent attacks.

Graham says the project has collected no data on violent incidents, but says an increase in perceptions of safety reported by surveyed residents is an indicator of success.

But as an answer to the vulnerability of Khayelitsha’s informal workers, the effort may be undermined by a new law that identifies informal workers themselves as a kind of “broken window” — and, seeking to tidy them away, might increase their risk. TheLicensing of Businesses Bill would force informal businesses (and other businesses) to apply for licenses from the government. Promoted by politician Lindiwe Zulu with explicit anti-immigrant sentiment, the bill has been opposed for promoting scarcity-obsessed xenophobia — the breeding ground for further violence against informal workers.

A 2013 op-ed captures the irony, and adds a comment about other means of addressing violence: “Contraventions of the provisions of the Bill are punishable by up to ten years imprisonment and undisclosed fines. One wishes South Africa’s rapists were punished as severely.”

The “Health Horizons: Innovation and the Informal Economy” column is made possible with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation.

M. Sophia Newman is a freelance journalist whose writing has been published in the U.S., U.K., Bangladesh, Nepal and Japan. See more at msophianewman.com.

NYC Councilman Wants to Preserve Central Park Sunshine

(AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

New York City Councilman Mark Levine, chair of the parks committee, is trying to keep some sunshine in Central Park. Capital New York reports that the councilman will introduce legislation to create a task force that will assess the growing (literal) shadow the city’s skyscrapers are casting over city parks.

Though Levine doesn’t intend to go as far as the way of San Francisco and Boston, where “sunlight ordinances” are implemented to ensure height cap for buildings that line parks, Levine’s proposed legislation is only in the early stages of attempting to form a conclusive answer to the shadow of the “Billionaire’s Row” described in a 2013 New York Times op-ed.

“The shadows of the larger of these planned buildings would jut half a mile into the park at midday on the solstice and elongate to around a mile in length as they angled across the park toward the Upper East Side, darkening playgrounds and ball fields, as well as paths and green space like Sheep Meadow that are enjoyed by 38 million visitors each year,” wrote Warren St. John in the op-ed.

The high-rise buildings under development around Central Park include One57, a 90-story condominium criticized for both its height and its 421-a tax abatement, which is designed to incentivize affordable housing. One57’s units are selling for millions of dollars.

Levine believes regulating building height and keeping park space out of the shadows is a move that favors developers who should want parks to “remain vibrant places” — for the sake of real estate prices at least. Levine’s proposed task force would meet biannually to assess new developments that could potentially cast shadows and recommend methods of mitigating the issue.

Marielle Mondon is an editor and freelance journalist in Philadelphia. Her work has appeared inPhiladelphia City Paper, Wild Magazine, and PolicyMic. She previously reported on communities in Northern Manhattan while earning an M.S. in journalism from Columbia University.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered