Where Yinz At

Why Pennsylvania is the most linguistically rich state in the country.

Illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo

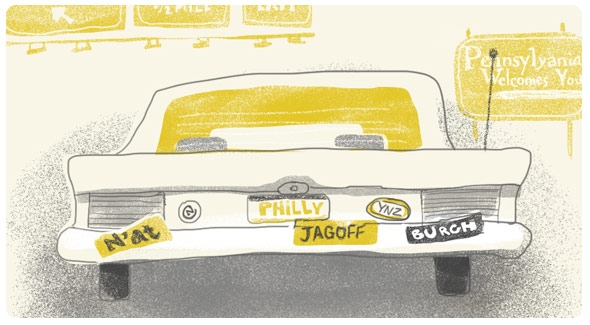

The 4 hour and 46 minute drive from

Philadelphia to Pittsburgh is marked by several things: barns, oddly

timed roadwork projects, four tunnels that lend themselves to

breath-holding competitions, turnpike rest stops featuring heat-lamped Sbarro

slices and overly goopy Cinnabon. But perhaps the most noteworthy—and

useful—hallmark of that road trip is all the bumper stickers that one

spies along the way.

From Center City Philly to about Reamstown, it’s all Eagles and

Phillies and Flyers stickers. Then there’s a 150-mile stretch of road

where anything goes. Penn State paraphernalia, Jesus fish, and stickers

about deer hunting mix with every other form of car commentary to create

a hodgepodge that predominates until about Bedford. From there, it

really is all Steelers stuff. And for those who make this drive fairly

often, that bumper sticker progression serves as an old-school GPS. Of

course, you’ll also spot stickers referencing cheesesteak lingo, as well

as those emblazoned with “N’AT,”

on this trip. And if you’re from out of state and decide to rest-stop

query the owner of a car bearing one of those stickers, within the first

few words of that person’s spoken response you’ll realize why linguists

love the Keystone State.

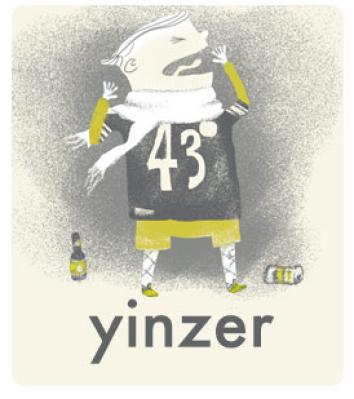

Pennsylvania, in case yinz didn’t know, is a regional dialect hotbed

nonpareil. A typical state maintains two or three distinct,

comprehensive dialects within its borders. Pennsylvania boasts five,

each consisting of unique pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar

elements. Of course, three of the five kind of get the shaft—sorry Erie,

and no offense, Pennsylvania Dutch Country—because by far the most

widely recognized Pennsylvania regional dialects are those associated

with Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

The Philadelphia dialect features a focused avoidance of the “th” sound, the swallowing of the L in lots of words, and wooder instead of water, among a zillion other things. In Pittsburgh, it’s dahntahn for downtown, and words like nebby and jagoff and yinz.

But, really, attempting to describe zany regional dialects using

written words is a fool’s errand. To get some sense of how

Philadelphians talk, check out this crash course clip

created by Sean Monahan, who was raised in Bucks County speaking with a

heavy Philly accent. Then hit the “click below” buttons on the website

for these Yappin’ Yinzers dolls to get the Pittsburgh side of things, and watch this Kroll Show clip to experience a Pennsylvania dialect duel.

According to Barbara Johnstone,

a professor of English and linguistics at Carnegie Mellon University,

migration patterns and geography deserve much of the credit (or blame)

for the variety of speech quirks on display in Pennsylvania. A

horizontal dialect boundary that roughly traces Interstate 80

spans the length of the state.

The speech and vocabulary of those living north of that line of demarcation, she says, were influenced by those who migrated into the U.S. through Boston mainly from the south of England. “Whereas the people in the rest of Pennsylvania below that tended to come to the U.S. from Northern England and arrived in Philadelphia and other places along the Delaware Valley,” Johnstone says. “They came from Northern England and Scotland and Northern Ireland.”

The speech and vocabulary of those living north of that line of demarcation, she says, were influenced by those who migrated into the U.S. through Boston mainly from the south of England. “Whereas the people in the rest of Pennsylvania below that tended to come to the U.S. from Northern England and arrived in Philadelphia and other places along the Delaware Valley,” Johnstone says. “They came from Northern England and Scotland and Northern Ireland.”

Those living north of I-80 have historically used different words for

certain things than those living in the southern half of Pennsylvania—pail vs. bucket,

for instance. And the pronunciation of various vowel sounds north of

the boundary doesn’t align with how those vowels are pronounced in other

parts of the state. “Rot can sound, to south-of-I-80 ears, like rat,” she adds, “or bus, like boss.”

Illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo

Settlement in western Pennsylvania began to pick up around the time

of the American Revolution, and those who set down roots in the

area—predominantly Scotch-Irish families, followed by immigrants from

Poland and other parts of Europe—tended to stay put as a result of the

Allegheny Mountains, which bisect the state diagonally from northeast to

southwest. “The Pittsburgh area was sort of isolated,” says Johnstone.

“It was very hard to get back and forth across the mountains. There’s

always been a sense that Pittsburgh was kind of a place unto itself—not

really southern, not really Midwestern, not really part of Pennsylvania.

People just didn’t move very much.”

The result was a scenario in which—with some exceptions, such as the transfer of the word hoagie

from Philly to Pittsburgh—the two dialects could develop and grow

independently. Fast-forward 250 years or so, and people from Pittsburgh

are talking about “gettin’ off the caach and gone dahntawn on the trawly

to see the fahrworks for the Fourth a July hawliday n’at,” while

Philadelphia folks provide linguistic gems like the one Monahan offered

up as the most Philly sentence possible: “Yo Antny, when you’re done

your glass of wooder, wanna get a hoagie on Thirdyfish Street awn da way

over to Moik’s for de Iggles game?”

He deciphered the easy elements—like “Antny” (Anthony), “hoagie”

(submarine sandwich), “Iggles” (the Philadelphia Eagles)—before

transitioning to the more upper-level material. “We have this very

unusual grammar quirk with the word done,” Monahan explains. “When you say ‘I’m done’ something, it means the task is done. The rest of the country would say ‘I’m done with

my water.’ But if I say ‘I’m done with my water’ in Philadelphia, that

would mean I’ve had some, and I don’t want to finish the rest. If I say

‘I’m done my water,’ that means I’ve drunk all of it. They mean two

different things.”

Illustration by Natalie Matthews-Ramo

That’s not really the case anywhere else in the country. There also

aren’t many places, he adds, where people refer to someone named Mike as

“Moik” in conversation. “That ‘oi’ is what I would call the defining

Philadelphia sound in the way that the Philly accent is today,” Monahan

says. As for “Thirdyfish Street”? That’s “Thirty-fifth Street” to you

and me. Philadelphians often replace “th”s in words with other sounds,

though, and “everything just winds up getting all blurred together.”

According to University of Pennsylvania linguistics professor William Labov,

the Philly dialect represents a tug of war between the city’s

connections to, and influences from, different parts of the country. “I

think Philadelphia is torn between its northern and southern heritage,”

he says. The result is a regional dialect that combines many influences

to form a one-of-a-kind manner of speaking. And, he adds, it’s a way of

speaking that has become a source of pride for many residents.

Labov is currently working on a project at Penn that involves interviewing students who have graduated from Philadelphia high schools to determine their perceptions about Philly. “Most are very positive about the city and see themselves staying in Philadelphia,” he says. “As far as the dialect is concerned, only a few points have become self-conscious. For most of Philadelphia, the general attitude is quite positive.”

Labov is currently working on a project at Penn that involves interviewing students who have graduated from Philadelphia high schools to determine their perceptions about Philly. “Most are very positive about the city and see themselves staying in Philadelphia,” he says. “As far as the dialect is concerned, only a few points have become self-conscious. For most of Philadelphia, the general attitude is quite positive.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered