Cloning used to make stem cells from adult humans

Story highlights

- In two new studies, adult skin cells were used to make embryos

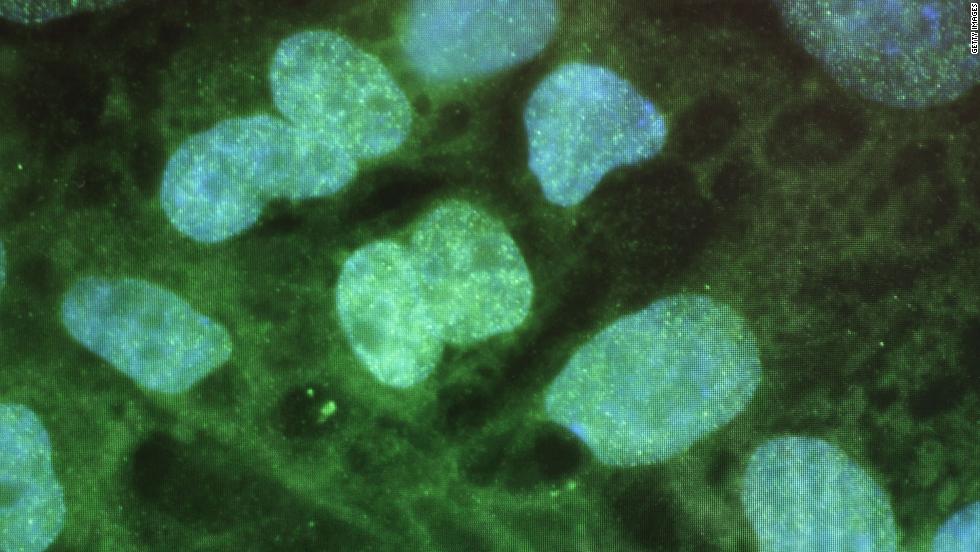

- Stem cells can grow into any kind of tissue

- Many future medical advances are hoped to arise from stem cells

For the first time, cloning technologies have been used to generate stem cells that are genetically matched toadult patients.

Fear not: No legitimate scientist is in the business of cloning humans. But cloned embryos can be used as a source for stem cells that match a patient and can produce any cell type in that person.

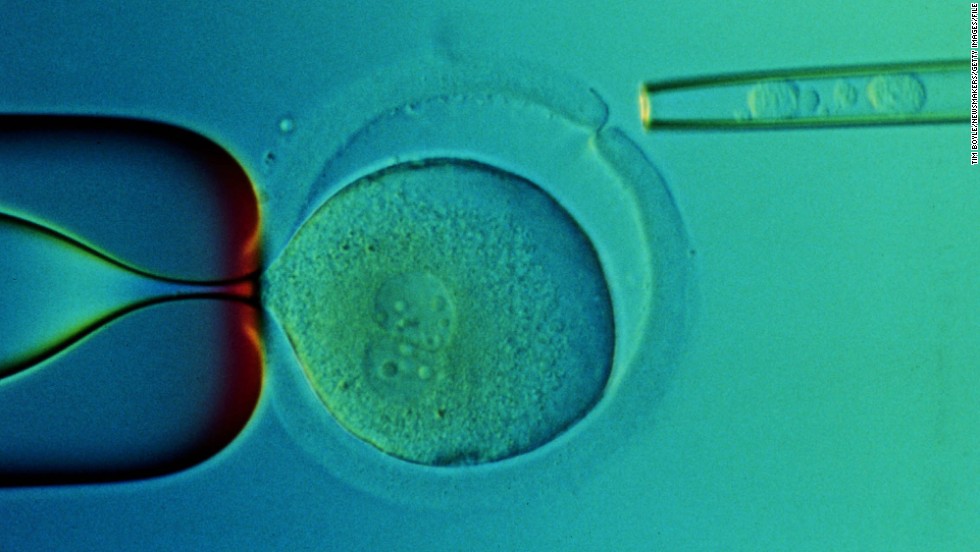

Researchers in two studies published this month have created human embryos for this purpose. Usually an embryo forms when sperm fertilizes egg; in this case, scientists put the nucleus of an adult skin cell inside an egg, and that reconstructed egg went through the initial stages of embryonic development.

"This is a dream that we've had for 15 years or so in the stem cell field," said John Gearhart, director of the Institute for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Gearhart first proposed this approach for patient-specific stem cell generation in the 1990s but was not involved in the recent studies.

Stem cells have the potential to develop into any kind of tissue in the human body. From growing organs to treating diabetes, many future medical advances are hoped to arise from stem cells.

Scientists wrote in the journal Cell Stem Cell this month that they used skin cells from a man, 35, and another man, 75, to create stem cells from cloned embryos.

"We reaffirmed that it is possible to produce patient-specific stem cells using a nuclear transfer technology regardless of the patient's age," said co-lead author Young Gie Chung at the CHA Stem Cell Institute in Seoul, South Korea.

On Monday, an independent group led by scientists at the New York Stem Cell Foundation Research Institute published results in Nature using a similar approach. They used skin cells from a 32-year-old woman with Type 1 diabetes to generate stem cells matched to her.

Human cloning: One step closer04:16

Both new reports follow the groundbreaking research published last year by Shoukhrat Mitalipov and colleagues at Oregon Health & Science University in the journal Cell. In that study, researchers produced cloned embryos and stem cells using skin cells from a fetus and an 8-month-old baby.

"It's a remarkable process that gives us these master cells, these stems cells that are essentially the seeds for all of the tissues in our bodies," said George Daley, director of the Stem Cell Transplantation Program at Boston Children's Hospital, who was not involved in the recent studies. "That's why it's so important for medical research."

A brief history of stem cells

The first developments in the field of stem cell research used leftover embryos created by the union of sperm and egg from in vitro fertilization.

But embryonic stem cell research is controversial because to use the stem cells for developing medical treatments, the embryo is destroyed. Embryos have the potential to develop into a fully formed human, bringing up ethical questions.

Scientists later realized that it's not necessary to use embryos to obtain stem cells that match patients. Shinya Yamanaka won the 2012 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for discovering how to make "induced pluripotent stem cells," or IPS cells.

IPS cells are made by inserting genes to "turn back the clock" on mature cells that already have specific functions. It doesn't matter what the cell was before; it can now be reprogrammed as any kind of cell researchers want.

Why, then, would researchers bother to make stem cells using cloning, which requires human eggs and the creation of embryos?

"People have made patient-matched stem cells using IPS methods," said Dieter Egli, senior author on the Nature paper that could have implications for diabetes treatment and researcher at the New York Stem Cell Foundation. "But it is not clear in the U.S. at the very least, and also elsewhere, how and if these are going to be translated into people."

Egli points out that there have been some reports that IPS cells may have shortcomings when converted into specific cell types, and that stem cells produced by cloning may be better.

But which stem cell type is better and safer -- the IPS cells or cells from cloned embryos? That is still an open question. To settle it, there would need to be a comparison of the two stem cell types generated using the DNA of the same person.

Gearhart doesn't see the cloning method replacing the use of IPS cells, which are not controversial and don't require that women donate their eggs.

"As we learn more about the reprogramming process that normally occurs in the egg following fertilization, we can use that information to produce better IPS cells," Gearhart said.

The process of extracting eggs is complex and expensive; having enough supply is a "serious concern," Daley said.

"The more we learn about reprogramming, the more I think IPS will be the one of choice," Gearhart said.

Making stem cells by cloning

An embryo, the earliest stage of human development, is a cluster of cells smaller than the period at the end of this sentence.

To make a cloned embryo, scientists use equipment analogous to "like a half-million-dollar video game," Daley said.

Researchers perform surgery on eggs with needles that are the 10th of the size of a human hair. They use joysticks to manipulate the tiny equipment, spearing the egg, removing its DNA and then transferring the nucleus of a skin cell into the egg.

"That process, which is called nuclear transfer, sets in motion this remarkable process of early human development," Daley said. "We trick this reconstructed egg into thinking it's been fertilized."

Chung's group -- which led the Cell Stem Cell study -- used this cloning method that Mitalipov had pioneered to get two stem cell lines out of 77 eggs. "It seems that the quality of oocyte (egg) plays a pivotal role," Chung said.

Egli and colleagues had their own spin on the cloning process, amending it so that it happens in a more controlled way. Their study in Nature used electricity in combination with chemicals, and manipulating the calcium concentration, to improve the procedure. They generated stem cells specific to the diabetic patient who had donated skin cells; the eggs came from donors.

This group got four cell lines from 71 eggs, said research assistant Lydia Mailander. The average egg donation is 14 to 15 oocytes. Researchers estimate it would take two such donations to get one stem cell line.

In mice, Egli and colleagues showed in a separate study that the cloned stem cells from the diabetic patient mature into glucose-responsive beta cells, which secrete insulin into the bloodstream of the animals.

Further considerations

It's not clear that there are enough eggs in supply to support a large-scale production of stem cells this way, experts said.

For the near-term research purposes, there seem to be enough eggs available for stem cell cloning: About 10,000 egg donor cycles occur annually in the United States, Egli said.

But egg donation for research is generally low, Gearhart said. According to the American Diabetes Association, about 1 million Americans have Type 1 diabetes, the target population for a potential stem cell therapy.

The cloning method takes a few weeks, and is not significantly faster than generating IPS cells, Egli said.

Including compensation to the woman, an egg donation cycle costs about $14,000, Egli said.

"It may not at all be more expensive (than IPS) if the cells that we make are actually better," he said. "That's why it's important to do these comparisons."

Such a comparison would be interesting, said Daley, but the advantages would have to be considerable to beat out IPS, which is "much more efficient and less ethically contentious that Yamanaka (the Nobel winner) taught us."

Still, from a research perspective, the cloning method could help scientists interested in understanding how an egg reprograms the cell, Daley said. It could help answer: "How does an egg reset the whole identity of an adult cell back to an embryonic state?"

Stem cell cloning research might, in this way, teach scientists how to make stem cells more efficiently, he said, and optimize them for medical applications.

How about making a clone?

Mitalipov told CNN in 2013 that the embryos created in his study, from skin cells and eggs, would not grow babies. That would have required additional technology, and it wasn't part of the study.

But the same basic "nuclear transfer" principle used in Mitalipov's, Chung's and Egli's studies was used create Dolly the sheep, the first mammal clone.

In Dolly's case, an embryo created by nuclear transfer was transplanted to a ewe, which gave birth to a sheep.

In the case of human embryos generated in these stem cell experiments, "it would be dangerous and unethical to attempt to transfer them into a uterus," Daley said.

Star Trek legend became NASA's 'secret weapon'

Nichelle Nichols has spent her whole life going where no one has gone before, and at 81 she's still as sassy and straight-talking as you'd expect from an interstellar explorer.World's largest aquatic insect specimen found in China

The world's largest flying aquatic insect, with huge, nightmarish pincers, has been discovered in China's Sichuan province.Cheating death through 'suspended animation'

As fans of "Grey's Anatomy," "ER" and any other hospital-based show can tell you, emergency-room doctors are fighting against time.At Harvard, swarming robots that mimic termites

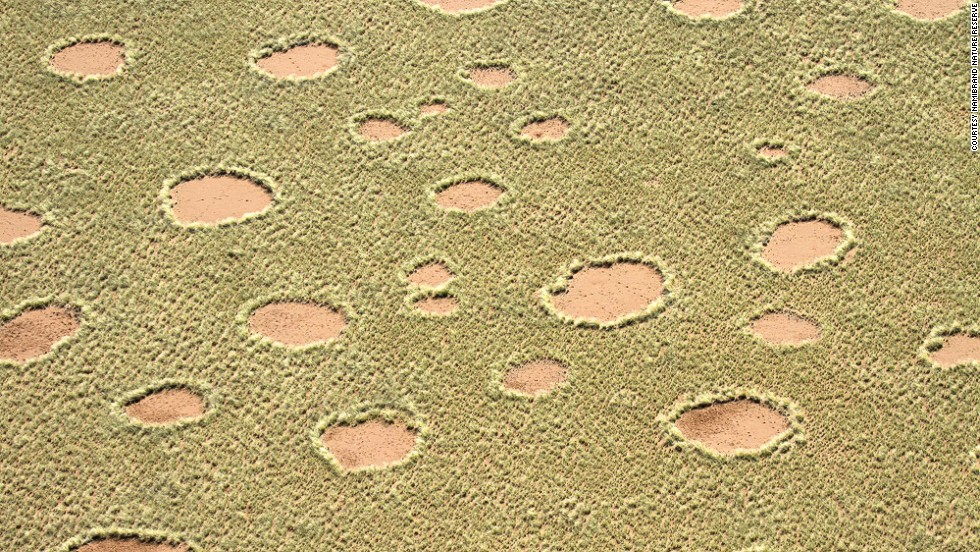

Ask 100 robotics scientists why they're inspired to create modern-day automatons and you may get 100 different answers.Namibia's 'fairy circles': Nature's greatest mystery?

From the air, the Namibian desert looks like it has a bad case of chicken pox.Incredible new tech inspired by biology

The trend for nature-inspired designs has spread across industries from crab-style deep-sea vessels to insect-inspired buildings.Top 10 newly discovered species

Consider it the taxonomist's equivalent of a People magazine's Most Beautiful List.New life engineered with artificial DNA

For the first time, scientists have shown it is possible to alter the biological alphabet and still have a living organism that passes on the genetic information.Should scientists bring extinct species back to life?

Do we really want to go the route of "Jurassic Park"?Vertical travel could transform your commute

Catch a train from the sky! Perhaps in the future, the high-rise superstructures could help revolutionize the way we travel.How test-tube meat could be the future of food

In a nondescript hotel ballroom last month at the South by Southwest Interactive festival, Andras Forgacs offered a rare glimpse at the sci-fi future of food.Dinosaur dubbed the 'chicken from hell'

For a Tyrannosaurus rex looking for a snack, nothing might have tasted quite like the "chicken from hell."Itsy bitsy dinosaur was T. rex cousin

Everyone is familiar with Tyrannosaurus rex, but humanity is only now meeting its much smaller Arctic cousin.Biggest predator ever to stalk Europe

At about 33 feet long, weighing 4 to 5 tons and baring large blade-shaped teeth, the dinosaur Torvosaurus gurneyi was a formidable creature.'Very strange-looking' dinosaur skull found

This Pachyrhinosaurus can go to the head of its class.How your brain makes moral judgments

Science is still trying to work out how exactly we reason through moral problems, and how we judge others on the morality of their actions. But patterns are emerging.FDA considering '3-parent babies'

A promising way to stop a deadly disease, or an uncomfortable step toward what one leading ethicist called eugenics?Huge mammoth tusk discovered

Seattle paleontologists safely removed the largest fossilized mammoth tusk discovered in the region from a construction site.Mysterious structure in ancient lake

A mysterious, circular structure, with a diameter greater than the length of a Boeing 747 jet, has been discovered submerged about 30 feet underneath the Sea of Galilee in Israel.Blood Falls and other oddities

Every corner of the planet offers some sort of natural peculiarity with an explanation that makes us wish we'd studied harder in junior high Earth science class.3.5 billion year old life in Australia

Deep in a remote, hot, dry patch of northwestern Australia lies one of the earliest detectable signs of life on the planet, tracing back nearly 3.5 billion years, scientists say.Artist creates faces from random DNA

We leave genetic traces of ourselves wherever we go -- in a strand of hair left on the subway or in saliva on the side of a glass at a cafe.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered