I pour tremendous time, thought, love, and resources into Brain Pickings, which remains free. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider supporting my labor of love with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner:

You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount:

And if you've already donated, from the bottom of my heart: THANK YOU.

|

“In its passivity and resignation, cynicism is a hardening, a calcification of the soul. Hope is a stretching of its ligaments, a limber reach for something greater.â€

|

Hello, Larry! If you missed last week's edition – Louise Bourgeois on solitude, my commencement address about the soul-sustaining necessity of resisting self-comparison and fighting cynicism, Audre Lorde on silence, Bertrand Russell on freedom of thought and our only defense against propaganda, and more – you can catch up right here. If you're enjoying my newsletter, please consider supporting this labor of love with a donation – I spend countless hours and tremendous resources on it, and every little bit of support helps enormously. Hello, Larry! If you missed last week's edition – Louise Bourgeois on solitude, my commencement address about the soul-sustaining necessity of resisting self-comparison and fighting cynicism, Audre Lorde on silence, Bertrand Russell on freedom of thought and our only defense against propaganda, and more – you can catch up right here. If you're enjoying my newsletter, please consider supporting this labor of love with a donation – I spend countless hours and tremendous resources on it, and every little bit of support helps enormously.

|

I have thought and continued to think a great deal about the relationship between critical thinking and cynicism — what is the tipping point past which critical thinking, that centerpiece of reason so vital to human progress and intellectual life, stops mobilizing our constructive impulses and topples over into the destructiveness of impotent complaint and embittered resignation, begetting cynicism? In giving a commencement address on the subject, I found myself contemplating anew this fine but firm line between critical thinking and cynical complaint. To cross it is to exile ourselves from the land of active reason and enter a limbo of resigned inaction.

But cross it we do, perhaps nowhere more readily than in our capacity for merciless self-criticism. We tend to go far beyond the self-corrective lucidity necessary for improving our shortcomings, instead berating and belittling ourselves for our foibles with a special kind of masochism.

The undergirding psychology of that impulse is what the English psychoanalytical writer Adam Phillips explores in his magnificent essay “Against Self-Criticismâ€, found in his altogether terrific collection Unforbidden Pleasures ( public library).

In broaching the possibility of being, in some way, against self-criticism, we have to imagine a world in which celebration is less suspect than criticism; in which the alternatives of celebration and criticism are seen as a determined narrowing of the repertoire; and in which we praise whatever we can.

In Freud’s vision of things we are, above all, ambivalent animals: wherever we hate, we love; wherever we love, we hate. If someone can satisfy us, they can also frustrate us; and if someone can frustrate us, we always believe that they can satisfy us. We criticize when we are frustrated — or when we are trying to describe our frustration, however obliquely — and praise when we are more satisfied, and vice versa. Ambivalence does not, in the Freudian story, mean mixed feelings, it means opposing feelings.

[…]

Love and hate — a too simple, or too familiar, vocabulary, and so never quite the right names for what we might want to say — are the common source, the elemental feelings with which we apprehend the world; and they are interdependent in the sense that you can’t have one without the other, and that they mutually inform each other. The way we hate people depends on the way we love them, and vice versa. And given that these contradictory feelings are our ‘common source’ they enter into everything we do. They are the medium in which we do everything. We are ambivalent, in Freud’s view, about anything and everything that matters to us; indeed, ambivalence is the way we recognize that someone or something has become significant to us… Where there is devotion there is always protest… where there is trust there is suspicion.

[…]

We may not be able to imagine a life in which we don’t spend a large amount of our time criticizing ourselves and others; but we should keep in mind the self-love that is always in play.

But we have become so indoctrinated in this conscience of self-criticism, both collectively and individually, that we’ve grown reflexively suspicious of that alternative possibility. (Kafka, the great patron-martyr of self-criticism, captured this pathology perfectly: “There’s only one thing certain. That is one’s own inadequacy.â€) Phillips writes:

Self-criticism, and the self as critical, are essential to our sense, our picture, of our so-called selves.

[…]

Nothing makes us more critical, more confounded — more suspicious, or appalled, or even mildly amused — than the suggestion that we should drop all this relentless criticism; that we should be less impressed by it. Or at least that self-criticism should cease to have the hold over us that it does.

But this self-critical part of ourselves, Phillips points out, is “strikingly unimaginative†— a relentless complainer whose repertoire of tirades is so redundant as to become, to any objective observer, risible and tragic at the same time:

Were we to meet this figure socially, as it were, this accusatory character, this internal critic, we would think there was something wrong with him. He would just be boring and cruel. We might think that something terrible had happened to him. That he was living in the aftermath, in the fallout of some catastrophe. And we would be right.

Freud termed this droll internal critic superego, and Phillips suggests that we suffer from a kind of Stockholm syndrome of the superego:

We are continually, if unconsciously, mutilating and deforming our own character. Indeed, so unrelenting is this internal violence that we have no idea what we are like without it. We know virtually nothing about ourselves because we judge ourselves before we have a chance to see ourselves (as though in panic). Or, to put it differently, we can judge only what we recognize ourselves as able to judge. What can’t be judged can’t be seen. What happens to everything that is not subject to approval or disapproval, to everything that we have not been taught how to judge? … The judged self can only be judged but not known. [We] think that it is complicitous not to stand up to, not to contest, this internal tyranny by what is only one part — a small but loud part — of the self.

The tyranny of the superego, Phillips argues, lies in its tendency to reduce the complexity of our conscience to a single, limiting interpretation, and to convincingly sell us on that interpretation as an accurate and complete representation of reality:

Self-criticism is nothing if it is not the defining, and usually the overdefining, of the limits of being. But, ironically, if that’s the right word, the limits of being are announced and enforced before so-called being has had much of a chance to speak for itself.

[…]

We consent to the superego’s interpretation; we believe our self-reproaches are true; we are overimpressed without noticing that that is what we are being.

With an eye to Freud’s legacy and the familiar texture of the human experience, Phillips makes his central point:

You can only understand anything that matters — dreams, neurotic symptoms, literature — by overinterpreting it; by seeing it from different aspects as the product of multiple impulses. Overinterpretation here means not settling for one interpretation, however apparently compelling it is. Indeed, the implication is — and here is Freud’s ongoing suspicion, or ambivalence, about psychoanalysis — that the more persuasive, the more compelling, the more authoritative, the interpretation is, the less credible it is, or should be. The interpretation might be the violent attempt to presume to set a limit where no limit can be set.

Here, the ideological wink at Sontag becomes apparent. Indeed, the Sontag classic would’ve been better titled “Against an Interpretation,†for the essence of her argument is precisely that a single interpretation invariably warps and flattens any text, any experience, any cultural artifact. (How tragicomical to see, then, that a reviewer who complains that Phillips’s writing is too open to interpretation both misses his point and, in doing so, makes it.)

What Phillips is advocating isn’t the wholesale relinquishing of interpretation but the psychological hygiene of inviting multiple interpretations as a way of countering the artificial authority of the superego and loosening its tyrannical grip on our experience of ourselves:

Authority wants to replace the world with itself. Overinterpretation means not being stopped in your tracks by what you are most persuaded by; it means assuming that to believe one interpretation is to radically misunderstand the object one is interpreting, and indeed interpretation itself.

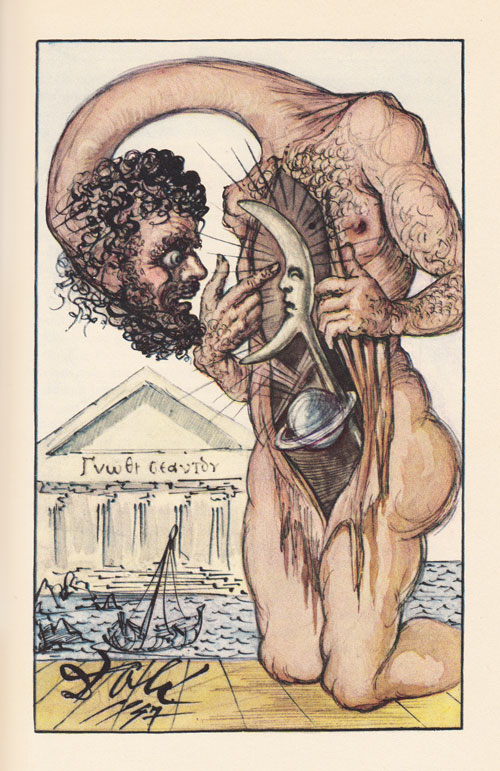

Illustration by Kate Beaton from To Be or Not To Be, a choose-your-own-adventure reimagining of Hamlet

Cuing in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, that “genius of self-reproach,†Phillips considers the cowardice of self-criticism:

Tragic heroes always underinterpret, are always emperors of one idea.

[…]

The first quarto of Hamlet has, “Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,†while the second quarto has, “Thus conscience does make cowards.†If conscience makes cowards of us all, then we are all in the same boat; this is just the way it is. If conscience simply makes cowards we can more easily wonder what else it might be able to make. Either way, and they are clearly different, conscience makes something of us; it is a maker, if not of selves, then of something about selves. It is an internal artist, of a kind… The superego … casts us as certain kinds of character: it, as it were, tells us who we really are. It is an essentialist: it claims to know us in a way that no one else, including ourselves, can ever do. And, like a mad god, it is omniscient: it behaves as if it can predict the future by claiming to know the consequences of our actions (when we know, in a more imaginative part of ourselves, that most actions are morally equivocal, and change over time in our estimation; no apparently self-destructive act is ever only self-destructive; no good is purely and simply that).

The superego is the sovereign interpreter… [It] tells us what we take to be the truth about ourselves. Self-criticism, that is to say, is an unforbidden pleasure. We seem to relish the way it makes us suffer [and] take it for granted that each day will bring its necessary quotient of self-disappointment. That every day we will fail to be as good as we should be; but without our being given the resources, the language, to wonder who or what is setting the pace; or where these rather punishing standards come from.

Under this docile surrender to self-criticism, Phillips cautions, our conscience slips into cowardice:

Conscience … it is the part of our mind that makes us lose our minds; the moralist that prevents us from evolving a personal, more complex and subtle morality; that prevents us from finding, by experiment, what may be the limits of our being. So when Richard III says, in the final act of his own play, “O coward conscience, how dost thou afflict me!â€, a radical alternative is being proposed. That conscience makes cowards of us all because it is itself cowardly. We believe in, we identify with, this starkly condemnatory and punitively forbidding part of ourselves; and yet this supposedly authoritative part of ourselves is itself a coward.

The most virulent and culturally contagious form of this cowardice, I would argue, is the resignation of cynicism — a resignation Phillips traces to the punitive system at the root of our culture’s moral framework, in which good behavior is incentivized largely through fear of punishment for bad behavior. This effort to foster the constructive by the destructive, he suggests, ends up turning us on ourselves as our fear of punishment metastasizes into self-criticism. (The cynic bypasses the constructiveness — that is, refuses to do anything about changing a situation for the better — and rushes straight to inflicting punishment, be it by insult or condemnation or that most cowardly and passive-aggressive fusion of the two, the eyeroll.)

Phillips returns to the central paradox, arguing for the importance of overinerpreting our self-critical conscience:

How has it come about that we are so bewitched by our self-hatred, so impressed and credulous in the face of our self-criticism, as unimaginative as it usually is? And why is it akin to a judgement without a jury? A jury, after all, represents some kind of consensus as an alternative to autocracy… We need to be able to tell the difference between useful forms of responsibility taken for acts committed, and the evasions of self-contempt… This doesn’t mean that no one is ever culpable; it means that culpability will always be more complicated than it looks; guilt is always underinterpreted… Self-criticism, when it isn’t useful in the way any self-correcting approach can be, is self-hypnosis. It is judgement as spell, or curse, not as conversation; it is an order, not a negotiation; it is dogma, not overinterpretation.

Our self-criticism, to be sure, couldn’t be entirely eradicated — nor should it, for it is our most essential route-recalculating tool for navigating life. But by nurturing our capacity for multiple interpretations, Phillips suggests, self-criticism can become “less jaded and jading, more imaginative and less spiteful.â€

Instead of consciously considering the semantic aspect of the images and vignettes she drew for each of the letters, Isol let the shape of the letter lead her brush toward a spontaneous burst of visual meaning — a sort of creative game that produced something utterly magical, more dream than dictionary, populated by kiwis and caterpillars and otherworldly creatures animated by the most inescapable emotional dimensions of human life: loneliness, gladness, petulance, tenderness, joy.

Isol reflects on how this playful exploration of shape and meaning guided her creative process:

I started by writing the letters the way I did in school: first printing them, then in cursive, uppercase, lowercase. After, I created images to put beside them. Finally I found the words to connect them. Words are a wonderful kind of glue.

[…]

When I look at these pages now I see that the letters have made friends with their images, as though they’ve known each other forever.

Isol wrote the book in her native Spanish, then translated each of the words into English — “a kind of reinvention†that became its own creative project as the words and images “found new ways to live together.â€

What reader could be more demanding than a child? Children have a lot of things to discover and I’d better be on their high level in order to satisfy their huge capacity for curiosity. I get my inspiration from what’s wild, from what’s ridiculous, from that independence of culture that children enjoy. They are beyond our conventions, they keep asking themselves all sorts of things.

The great Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky described the art of cinema as “sculpting in time,†asserting that people go to the movies because they long to experience “time lost or spent or not yet had.†A century earlier, the English photographer Eadweard Muybridge (April 9, 1830–May 8, 1904) exposed the bedrock of time and devised the first chisel for its sculpting in his pioneering photographic studies of motion, which forever changed the modern world — not only by ushering in a technological revolution the effects of which permeate and even dictate our daily lives today, but also, given how bound up in space and time our thinking ego is, transforming our very consciousness. For the very first time, Muybridge’s motion studies captured what T.S. Eliot would later call “the still point of the turning world.â€

Eadweard Muybridge: The Horse in Motion

Solnit frames the impact of the trailblazing experiments Muybridge conducted in the spring of 1872, when he first photographed a galloping horse:

[Muybridge] had captured aspects of motion whose speed had made them as invisible as the moons of Jupiter before the telescope, and he had found a way to set them back in motion. It was as though he had grasped time itself, made it stand still, and then made it run again, over and over. Time was at his command as it had never been at anyone’s before. A new world had opened up for science, for art, for entertainment, for consciousness, and an old world had retreated farther.

Technology and consciousness, of course, have always shaped one another, perhaps nowhere more so than in our experience of time — from the moment Galileo’s invention of the clock sparked modern timekeeping to the brutality with which social media timelines beleaguer us with a crushing sense of perpetual urgency. But the 1870s were a particularly fecund zeitgeist of technological transformation by Solnit’s perfect definition of technology as “a practice, a technique, or a device for altering the world or the experience of the world.†She writes:

The experience of time was itself changing dramatically during Muybridge’s seventy-four years, hardly ever more dramatically than in the 1870s. In that decade the newly invented telephone and phonograph were added to photography, telegraphy, and the railroad as instruments for “annihilating time and space.â€

[…]

The modern world, the world we live in, began then, and Muybridge helped launch it.

[…]

His trajectory ripped through all the central stories of his time — the relationship to the natural world and the industrialization of the human world, the Indian wars, the new technologies and their impact on perception and consciousness. He is the man who split the second, as dramatic and far-reaching an action as the splitting of the atom.

Eadweard Muybridge: Sequenced image of a rotating sulky wheel with self-portrait

Shining a sidewise gleam at just how radically the givens we take for granted have changed since Muybridge’s time, Solnit writes of that era in which a man could shoot his wife’s lover and be acquitted for justifiable homicide:

In the eight years of his motion-study experiments in California, he also became a father, a murderer, and a widower, invented a clock, patented two photographic innovations, achieved international renown as an artist and a scientist, and completed four other major photographic projects.

With the invention of cinema still more than a decade away, Muybridge’s shutters and film development techniques fused cutting-edge engineering and chemistry to produce more and better high-speed photographs than anyone had before. In a sense, Virginia Woolf’s famous complaint about the visual language of cinema — “the eye licks it all up instantaneously, and the brain, agreeably titillated, settles down to watch things happening without bestirring itself to think,†she scoffed in 1926 — was an indictment of this new visual language of time and, indirectly, of Muybridge’s legacy. Had he not rendered time visible and tangible, Bertrand Russell may not have proclaimed that “even though time be real, to realize the unimportance of time is the gate of wisdomâ€; had his pioneering photography not altered our relationship to the moment, Italo Calvino would not have had to issue his prescient lamentation that “the life that you live in order to photograph it is already, at the outset, a commemoration of itself.â€

Eadweard Muyridge: A man standing on his hands from a lying down position

In a testament to the notion that all creative work builds on what came before, Muybridge made significant improvements on the zoetrope — a rotating device, invented in 1834, which creates the illusion of motion by presenting a series of spinning images through a slot. But alongside the practical improvement upon existing technologies, he also built upon larger cultural leaps — most significantly, the rise of the railroads, which compressed space and time unlike anything ever had.

In 1872, the railroad magnate Leland Stanford — who would later co-found Stanford University with his wife, Jane — commissioned Muybridge to study the gaits of galloping and trotting horses in order to determine whether all four feet lifted off the ground at once at any point. Since horses gallop at a speed that outpaces the perception of the human eye, this was impossible to discern without freezing motion into a still image. So began Muybridge’s transformation of time.

Horse in Motion: One of Muybridge’s motion studies commissioned by Stanford

With her penchant for cultural history laced with subtle, perfectly placed political commentary, Solnit traces the common root of Hollywood and Silicon Valley to Muybridge:

Perhaps because California has no past — no past, at least, that it is willing to remember — it has always been peculiarly adept at trailblazing the future. We live in the future launched there.

If one wanted to find an absolute beginning point, a creation story, for California’s two greatest transformations of the world, these experiments with horse and camera would be it. Out of these first lost snapshots eventually came a world-changing industry, and out of the many places where movies are made, one particular place: Hollywood. The man who owned the horse and sponsored the project believed in the union of science and business and founded the university that much later generated another industry identified, like Hollywood, by its central place: Silicon Valley.

It would be impossible to grasp the profound influence Muybridge and his legacy had on culture without understanding how dramatically different the world he was born into was from the one he left. Solnit paints the technological backdrop of his childhood:

Pigeons were the fastest communications technology; horses were the fastest transportation technology; the barges moved at the speed of the river or the pace of the horses that pulled them along the canals. Nature itself was the limit of speed: humans could only harness water, wind, birds, beasts. Born into this almost medievally slow world, the impatient, ambitious, inventive Muybridge would leave it and link himself instead to the fastest and newest technologies of the day.

The first passenger railroad opened on September 15, 1830 — mere months after Muybridge’s birth. Like any technological bubble, the spread of this novelty brought with it an arsenal of stock vocabulary. The notion of “annihilating time and space†became one of the era’s most used, then invariably overused, catchphrases. (In a way, clichés themselves — phrases to which we turn for cognitive convenience, out of a certain impatience with language — are another manifestation of our defiant relationship to time.) Applied first to the railways, the phrase soon spread to the various technological advancements that radiated, directly or indirectly, from them. Solnit writes:

“Annihilating time and space†is what most new technologies aspire to do: technology regards the very terms of our bodily existence as burdensome. Annihilating time and space most directly means accelerating communications and transportation. The domestication of the horse and the invention of the wheel sped up the rate and volume of transit; the invention of writing made it possible for stories to reach farther across time and space than their tellers and stay more stable than memory; and new communications, reproduction, and transportation technologies only continue the process. What distinguishes a technological world is that the terms of nature are obscured; one need not live quite in the present or the local.

[…]

The devices for such annihilation poured forth faster and faster, as though inventiveness and impatience had sped and multiplied too.

Eadweard Muybridge: Running full speed (Animal Locomotion, Plate 62)

But perhaps the most significant impact of the railroads, Solnit argues, was that they began standardizing human experience as goods, people, and their values traveled faster and farther than ever before. In contracting the world, the railways began to homogenize it. And just as society was adjusting to this new mode of relating to itself, another transformative invention bookended the decade: On January 7, 1839, the French artist Louis Daguerre debuted what he called daguerreotypy — a pioneering imaging method that catalyzed the dawn of photography.

With an eye to the era’s European and American empiricism, animated by a “restlessness that regarded the unknown as a challenge rather than a danger,†Solnit writes:

Photography may have been its most paradoxical invention: a technological breakthrough for holding onto the past, a technology always rushing forward, always looking backward.

[…]

Photography was a profound transformation of the world it entered. Before, every face, every place, every event, had been unique, seen only once and then lost forever among the changes of age, light, time. The past existed only in memory and interpretation, and the world beyond one’s own experience was mostly stories… [Now,] every photograph was a moment snatched from the river of time.

The final invention in the decades’s trifecta of technological transformation was the telegraph. Together, these three developments — photography, the railroads, and the telegraph — marked the beginning of our modern flight from presence, which would become the seedbed of our unhappiness over the century that followed. By chance, Muybridge came into the world at the pinnacle of this transformation; by choice, he became instrumental in guiding its course and, in effect, shaping modernity.

Eadweard Muybridge: Cockatoo flying (Animal Locomotion, Plate 758)

Solnit writes:

Before the new technologies and ideas, time was a river in which human beings were immersed, moving steadily on the current, never faster than the speeds of nature — of currents, of wind, of muscles. Trains liberated them from the flow of the river, or isolated them from it. Photography appears on this scene as though someone had found a way to freeze the water of passing time; appearances that were once as fluid as water running through one’s fingers became solid objects… Appearances were permanent, information was instantaneous, travel exceeded the fastest speed of bird, beast, and man. It was no longer a natural world in the sense it always had been, and human beings were no longer contained within nature.

Time itself had been of a different texture, a different pace, in the world Muybridge was born into. It had not yet become a scarce commodity to be measured out in ever smaller increments as clocks acquired second hands, as watches became more affordable mass-market commodities, as exacting schedules began to intrude into more and more activities. Only prayer had been precisely scheduled in the old society, and church bells had been the primary source of time measurement.

Simone Weil once defined prayer as “absolutely unmixed attention,†and perhaps the commodification of time that started in the 1830s was the beginning of the end of our capacity for such attention; perhaps Muybridge was the horseman of our attentional apocalypse.

Eadweard Muybridge: Woman removing mantle

Solnit considers the magnitude of his ultimate impact on our experience of time:

In the spring of 1872 a man photographed a horse. With the motion studies that resulted it was as though he were returning bodies themselves to those who craved them — not bodies as they might daily be experienced, bodies as sensations of gravity, fatigue, strength, pleasure, but bodies become weightless images, bodies dissected and reconstructed by light and machine and fantasy.

[…]

What they had lost was solid; what they gained was made out of air. That exotic new world of images speeding by would become the true home of those who spent their Saturdays watching images beamed across the darkness of the movie theater, then their evenings watching images beamed through the atmosphere and brought home into a box like a camera obscura or a crystal ball, then their waking hours surfing the Internet wired like the old telegraph system. Muybridge was a doorway, a pivot between that old world and ours, and to follow him is to follow the choices that got us here.

If you're a Brain Pickings reader, you know that few living people elicit my intellectual admiration and spiritual affection more than writer Rebecca Solnit and On Beinghost Krista Tippett. Now you can hear the two of them in conversation — it might be the most enlivening 51 minutes you'll lend your ear to this year:

“You’ve got to tell the world how to treat you,â€James Baldwin observed in his terrific forgotten conversation with Margaret Mead. “If the world tells you how you are going to be treated, you are in trouble.†A generation later, the great poet (both in the literal and in the Baldwian sense), essayist, playwright, memoirist, and beloved professor Elizabeth Alexander explores the trying, triumphant art of that telling in Power and Possibility: Essays, Reviews, and Interviews ( public library) — a slim, towering treasure of a book.

Weaving together history, literature, politics, and personal experience, Alexander — who became the fourth poet in history to read at a U.S. presidential inauguration when she welcomed Barack Obama to the presidency with her poem “Praise Song for the Day†— examines the rewards and challenges of being a black woman, a poet, an academic figure of authority and, above all, of inhabiting a culture in which the Venn diagram of these psychographic particulars is still lamentably improbable.

Radiating from these essays and interviews is incisive and generous insight into writing, the creative process, and the complexity of the self.

Elizabeth Alexander

I want to inject them with a serum that makes them believe what I now: that speaking is crucial, that you have to tell your own story simultaneously as you hear and respond to the stories of others, that education is not something you passively consume.

And yet the necessity of speaking and the authority of visibility come with a personal cost, which Alexander articulates with a vulnerable self-awareness tremendously inspiring amid our culture of invulnerable facades:

I have been in public discussions where my own paralysis had made me quiet or less articulate than I can be and kept me, perhaps, from being the role model a young woman needed at that moment. I now choose my battles and deal with the same beleagueredness that perhaps my teachers those years ago felt. I have learned that you can’t always be who others need you to be at any moment.

Alexander revisits this question in another interview:

I try to remember that you can get really distracted by the demands people make on you. Demands that are real are one thing, demands that come from a real community in need, or a real person in need. We’re asked all the time to be of service. But demands that are about posturing — you may have to deal with them, but I’m trying to figure out a way not to let them worm their way in too much.

Asserting that this obligation to the truth of one’s story must be “lived in our day-to-day lives, in the way we conduct the business of our lives, in the way we spend our money and raise our children and make a multitude of decisions every day,†Alexander considers the role of writing in inhabiting one’s visibility:

Great writing can make you face the truth around you and within yourself.

In another interview from the collection, Alexander turns to the transmutation of personal truth into writing:

A lot of my poetry comes from “personal†or autobiographical material. What is the transformation that has to happen in order for those details and that realm of personal to work within a poem? I can’t really say that I could anatomize it, but I know that there’s a transformation that has to take place.

Citing Sterling Brown’s pronouncement that “every I is a dramatic I†— a quote she wove into her beautiful poem “Ars Poetica #100: I Believe†— Alexander adds:

Regardless of whether or not you’re working in an autobiographical or personal mode, if there is a persona in the poem, you have certain charges to make it work dramatically in the poem itself. So, fulfilling those demands in the poem as such puts a nice set of parameters around the question of working within the infinite personal, because it’s quite infinite… The day-to-day me “I†[is] one level removed, or alchemized.

For any poem to succeed, whatever its rules, there are strict rules, or else the whole thing falls apart.

She recounts what the inimitable Derek Walcott, her only poetry teacher, taught her about writing and about the loaded interplay between personal identity and creative integrity:

He would always say never try to charm in your poems, never try to charm with your identity, it’s not enough that you’re a cute, black girl.

That was very useful advice, though I was already averse to exploiting “identity.†I think the point is, he’s saying, none of us as persona is ever enough. Whatever your identity, your set of particulars, there is going to be someone out there who thinks it’s fascinating unto itself. But that unto itself doesn’t make for a fine poem you could stand with. So he was also saying, don’t be swayed and don’t let praise go to your head. And don’t let it get into your writing, and don’t let it get into your quest.

But Alexander notes that there is a universe of difference between not being swayed by praise and being wholly impermeable, severing one’s connection to the world — a connection carried out through the authenticity of the word:

We live in the word. And the word is precious, and the word must be precise, and the word is one of the ways we have to reach across to each other, and … it has to be tended with that degree of respect… I believe that life itself is profoundly poetic, in all sorts of … guises and unexpected places.

Being open to those poetic surprises, Alexander argues, also requires a certain openness to the audience and to the range of possible receptions:

To be presumptuous about any kind of audience is not a good thing. I’ve had too many wonderful surprises… I’ve had many surprises with people who read poetry who I wouldn’t have imagined read poetry, that it has a place in their lives. You just really never know. You just can’t let that imagining get into the creative process because it would twist it and distort it and shut it down… Some people talk about the ideal reader, and I don’t really have an ideal reader… I just trust that when it goes out there, it will be found by whoever can make use of it… The beautiful thing about poetry is that you never now who will find it, and you never know what will be found in it.

Spiritual and ethical situations and conundrums are occasions for poems — though I am rarely aware of the conundrum as such when I embark upon the poem — and the writing of the poem is a way of working through those conundrums and accepting their frequent open-endedness. Besides making and raising children, the mystery of making art is the most spiritual zone of my life.

No matter how devoted we are to the culture and to each other, we have a lot to overcome, imagining ourselves, or imagining each other. And in receiving each other.

Language, Alexander argues, is the locus of reception — the medium in which we imagine ourselves and each other — something she captures beautifully in the piercing final line of a poem: “…and are we not of interest to each other?†She revisits the complexity of personal identity and considers how the self lives in language:

It’s all well and good to have an idea, to say, I want to write about such-and-such and such-and-such. But I think the idea has to be rooted in language. It has to live in language.

[…]

That’s what catches the imagination of somebody else, a listener or a reader. Even the way that we express ourselves as non-poet “civilians,†if you will, is what makes us interesting to other people… Who is the self in language? And what is the revelatory and unguarded and surprising self in language? That’s what makes somebody else pay attention. When you start turning that into art, that’s what making poems is about.

But this unguarded self in language, she argues, isn’t about “superseding the social identity, but it is about protecting the full dimension of the self.†And yet social identity and the poetics of personhood can never be fully disentwined from one another, nor unmoored from the wider cultural context. Alexander writes:

Being an empowered and intelligent black person and even more so being an empowered and intelligent and self-respecting black woman is profoundly destabilizing to most status quo. You’ve got to remember that in a way that’s not disabling.

Those [are] examples of brilliant, courageous, beautiful, engaged lives full of rampant loving, loving of the world. Loving of the work. Loving of each other. Moving toward what we love and not just toward the destruction of enemies… And that’s what I feel like it’s important to do upon rising each day.

When I was younger I used to think that love as an ethic was … obviously a good thing, but a little corny. I am certainly an optimist but not a fool. In academic environments, we are taught a skepticism that can lead us to discount the power and force of love. But the older I get, the more I think of all the possible permutations and possibilities of a love ethic. To love someone or something is not just to agree with them or affirm them. To bother to engage with problematic culture, and problematic people within that culture, is an act of love. So what does it mean in a complex and dead-serious way to come from that place of love?

When asked about the mental habits and practicalities of her creative process in writing poetry, Alexander offers:

I try to grab things when I can, to keep notes of things as I internally hear them so that when I do have writing time I have something to begin with.

[…]

Paper first, then the screen, for I feel bollixed up if I don’t attend to my internal soundtrack, so there is a personal satisfaction that comes from attending to it in writing. Also, at this point, twenty years into my life as a poet, I feel clearer about having something to say and people who benefit from hearing it.

I always tell student poets to read and listen as much and as variously as they can to build up a rolodex of possibilities in their minds when they sit down to write a poem. You always need to have many more possibilities of approaching a poem than you end up using… It’s about tuning your internal ear and listening to what the poem at hand is trying to do and be.

This internal process, Alexander enjoins, should be the primary focus of creative work:

Submit to it, tend it, nurture it, honor it. Too many young writers get distracted by thinking about career before process; without process, there is no real work and thus, no career. Every day is another blank page to be filled from your own particular landscape. Process it all.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered