Julian Assange

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Julian Assange | |

|---|---|

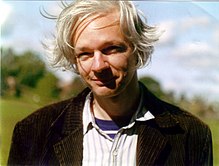

Assange in the Ecuadorian Embassy, London (August 2014)

| |

| Born | 3 July 1971 Townsville, Queensland, Australia |

| Residence | Embassy of Ecuador, London, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Alma mater | Central Queensland University University of Melbourne |

| Occupation | Editor-in-Chief of WikiLeaks |

| Home town | Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

Julian Paul Assange (born 3 July 1971) is an Australian computer programmer, publisher and journalist. He is known as the editor-in-chief of the website WikiLeaks, which he co-founded in 2006 after an earlier career in hackingand programming. WikiLeaks achieved particular prominence in 2010 when it published U.S. military and diplomatic documents leaked by Chelsea Manning. Assange has been under investigation in the United States since that time. In the same year, the Swedish Director of Public Prosecution opened an investigation into sexual offences that Assange is alleged to have committed.[1] In 2012, facing extradition to Sweden, he sought refuge at the Embassy of Ecuador in London and was granted political asylum by Ecuador.

Contents

[hide]Early life

Assange was born in the north Queensland city of Townsville,[2][3] to Christine Ann Assange (née Hawkins; b. 1951),[4] a visual artist,[5] and John Shipton, an anti-war activist and builder.[6] The couple had separated before Assange was born.[6]

When he was a year old, his mother married Richard Brett Assange,[7][8][9] an actor, with whom she ran "a small eccentric theatre company."[10] They divorced around 1979, and Assange's mother then became involved with Leif Meynell, also known as Leif Hamilton, a member of the Australian New Age group The Family, with whom she had a son before the couple broke up in 1982.[2][11][12] Assange had a nomadic childhood, and had lived in over thirty[13][14]different Australian towns by the time he reached his mid-teens, when he settled with his mother and half-brother in Melbourne, Victoria.[7][15]

He attended many schools, including Goolmangar Primary School in New South Wales (1979–1983)[10] and Townsville State High School,[16] as well as being schooled at home.[8] He studied programming, mathematics, and physics at Central Queensland University (1994)[17] and the University of Melbourne (2003–2006),[7][18] but did not complete a degree.[19]

Hacking

In 1987, Assange began hacking under the name Mendax (from Horace's splendide mendax: "nobly untruthful").[8][20] He and two others—known as "Trax" and "Prime Suspect"—formed an ethical hacking group they called the International Subversives.[8] During this time he hacked into the Pentagon and other U.S. Department of Defense facilities, MILNET, the U.S. Navy, NASA, and Australia's Overseas Telecommunications Commission; Citibank, Lockheed Martin, Motorola, Panasonic, and Xerox; and the Australian National University, La Trobe University, and Stanford University's SRI International.[21] He is thought to have been involved in the WANK (Worms Against Nuclear Killers) hack at NASA in 1989, but he does not acknowledge this.[22][23]

In September 1991, he was discovered hacking into the Melbourne master terminal of Nortel, a Canadian multinational telecommunications corporation.[8] The Australian Federal Police tapped Assange's phone line (he was using a modem), raided his home at the end of October,[24] and eventually charged him in 1994 with thirty-one counts of hacking and related crimes.[8] In December 1996, he pleaded guilty to twenty-five charges (the other six were dropped), and was ordered to pay reparations of A$2,100 and released on a good behaviour bond,[22][25] avoiding a heavier penalty due to the perceived absence of malicious or mercenary intent and his disrupted childhood.[26][27][28][29] After the trial, Assange lived in Melbourne, where he survived on single-parent income support.[25]

Programming

In 1993, Assange gave technical advice to the Victoria Police Child Exploitation Unit and assisted with prosecutions.[30] In the same year he was involved in starting one of the first public internet service providers in Australia, Suburbia Public Access Network.[7][31] He began programming in 1994, authoring or co-authoring the Transmission Control Protocol port scanner strobe.c (1995);[32][33] patches to the open-source database PostgreSQL (1996);[34][35] the Usenet caching software NNTPCache (1996);[36] the Rubberhose deniable encryptionsystem (1997),[37][38] which reflected his growing interest in cryptography;[39] and Surfraw, a command-line interface for web-based search engines (2000).[40] During this period he also moderated the AUCRYPTO forum;[39] ran Best of Security, a website "giving advice on computer security" that had 5,000 subscribers in 1996;[41] and contributed research to Suelette Dreyfus's Underground (1997), a book about Australian hackers, including the International Subversives.[20][42] In 1998, he co-founded the company Earthmen Technology.[28]

In 1999, Assange registered the domain leaks.org, but, as he put it, "I didn't do anything with it."[28][unreliable source?] He did, however, publicise a patent granted to the National Security Agency in August 1999 for voice-data harvesting technology: "This patent should worry people. Everyone's overseas phone calls are or may soon be tapped, transcribed and archived in the bowels of an unaccountable foreign spy agency."[39] This would remain an abiding concern, to which he returned more than a decade later in Cypherpunks (2012), foreseeing a dystopian future in which, "the Internet, our greatest tool for emancipation, has been transformed into the most dangerous facilitator of totalitarianism we have ever seen".[43]

WikiLeaks

Main article: WikiLeaks

After his period of study at the University of Melbourne, Assange and others established WikiLeaks in 2006. Assange is a member of the organisation's advisory board[44] and describes himself as the editor-in-chief.[45] From 2007 to 2010, Assange travelled continuously on WikiLeaks business, visiting Africa, Asia, Europe and North America.[8][14][46][47][48]

WikiLeaks published secret information, news leaks,[49] and classified media from anonymous sources.[50] The published material between 2006 and 2009 attracted various degrees of publicity,[51] but it was only after it began publishing documents supplied by Chelsea Manning that Wikileaks became a household name.[52] The Manning material included the Collateral Murder video (April 2010),[53] the Afghanistan war logs (July 2010), the Iraq war logs(October 2010), a quarter of a million diplomatic cables (November 2010), and the Guantánamo files (April 2011).

Opinions of Assange at this time were divided. Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard described his activities as "illegal,"[54] only to be told that he had broken no Australian law.[55] U.S. Vice President Joe Biden and others called him a "terrorist."[56][57][58][59][60] Some called for his assassination or execution.[61][62][63][64] Support came from people including the Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva,[65][66] Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin,[67][68] and activists and celebrities including Tariq Ali,[69] John Perry Barlow,[70] Daniel Ellsberg,[71][72] Mary Kostakidis,[73] John Pilger,[74][75] Vaughan Smith,[76][77] and Oliver Stone.[78]

The year 2010 culminated with the Sam Adams Award, which Assange accepted in October,[79] and a string of distinctions in December—the Le Monde readers' choice award for person of the year,[80][81] the Time readers' choice award for person of the year (he was also a runner-up in Time's overall person of the year award),[82][83] a deal for his autobiography worth at least US$1.3 million,[84][85][86] and selection by the Italian edition of Rolling Stone as "rockstar of the year."[87][88]

The following February he won the Sydney Peace Foundation Gold Medal for Peace with Justice, previously awarded to only three people—Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama, and Buddhist spiritual leader Daisaku Ikeda.[89] Two weeks later he filed for the trademark "Julian Assange" in Europe, which was to be used for "Public speaking services; news reporter services; journalism; publication of texts other than publicity texts; education services; entertainment services."[90][91][92] For several years a member of the Australian journalists' unionand still an honorary member,[93][94][95] he picked up the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism in June,[96][97] and the Walkley Award for Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism in November,[98][99] having earlier won the Amnesty International UK Media Award (New Media) in 2009.[100]

U.S. criminal investigation

After WikiLeaks released the Manning material, U.S. authorities began investigating WikiLeaks and Assange personally with a view to prosecuting them under the Espionage Act of 1917.[101] In November 2010, U.S. Attorney-General Eric Holder said there was "an active, ongoing criminal investigation" into WikiLeaks.[102] It emerged from legal documents leaked over the ensuing months that Assange and others were being investigated by a federal grand jury in Alexandria, Virginia.[103][104][105] An email from an employee of intelligence consultancy Strategic Forecasting, Inc. (Stratfor) leaked in 2012 said, "We have a sealed indictment on Assange."[106] The U.S. government denies the existence of such an indictment.[107][108]

In December 2011, prosecutors in the Chelsea Manning case revealed the existence of chat logs between Manning and an alleged WikiLeaks interlocutor they claimed to be Assange.[109][110] He "flatly" denies this,[111][112] dismissing the alleged connection as "absolute nonsense."[113] The logs were presented as evidence during Manning's court-martial in June–July 2013. The prosecution argued that they show WikiLeaks helping Manning reverse-engineer a password.[114][115] The evidence that the interlocutor was Assange is circumstantial, however, and Manning insists she acted alone.[105][115]

Assange was being examined separately by "several government agencies" in addition to the grand jury, most notably the FBI.[116] Court documents published in May 2014 suggest that Assange was still under "active and ongoing" investigation at that time.[117]

Swedish sex assault allegations

See also: Assange v Swedish Prosecution Authority

Assange is wanted for questioning over one count of unlawful coercion, two counts of sexual molestation, and one count of lesser-degree rape (mindre grov våldtäkt)[118] alleged to have been committed against two women during a visit to Sweden in August 2010.[119][120][121] Assange denies the allegations.[122][123]

On 7 December 2010, Assange was remanded in custody at London's Wandsworth Prison after a judge denied bail at a hearing considering his extradition to Sweden for criminal investigation into the sexual assault allegations against him.[124] On 16 December 2010, he was released on bail after another appeal.[125]

On 13 March 2015, in a reversal of their prior position on the matter, the Swedish prosecutors announced that they would be willing to interview Assange in the UK.[126]

On 11 May 2015, the Swedish Supreme court rejected Julian Assange's appeal against his arrest warrant.[127][128]

Political asylum and life at the Ecuadorian embassy

On 19 June 2012, Ecuadorian Foreign Minister Ricardo Patiño announced that Assange had applied for political asylum, that his government was considering the request, and that Assange was at the Ecuadorian embassy in London.[129][130][131][132]

On 16 August 2012, Foreign Minister Patiño announced that Ecuador was granting Assange political asylum.[133][134][135][136] Swedish lawyer Claes Borgström called Ecuador's decision "completely absurd" and "an abuse of the asylum instrument,"[137] a view echoed by others.[138][139][140] Latin American states expressed support for Ecuador.[141][142][143][144] Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa confirmed on 18 August that Assange could stay at the embassy indefinitely,[145][146][147] and the following day Assange gave his first speech from the balcony.[148][149][150][151] Assange's supporters forfeited £293,500 in bail[152] and sureties.[152][153]

His home since then has been an office converted into a studio apartment, equipped with a bed, telephone, sun lamp, computer, shower, treadmill, and kitchenette.[154][155][156] There was concern that the British police would try to extricate Assange from the embassy by force, but this did not occur.[157][158] Officers of the Metropolitan Police Service remain stationed outside the building to arrest him should he try to leave. The cost of the policing operation for the first two years of Assange's stay was £6.5 million.[159]

On 18 August 2014, Assange announced that he would be leaving the Ecuadorian embassy "soon."[160][161] While acknowledging that his health had "deteriorated," he emphasised that the announcement was prompted by "a range of important legal developments in the United Kingdom."[162]

Assange announced that he would run for the Australian Senate in March 2012 under the newly created WikiLeaks Party,[163][164] had his own talk show on Russia Today in April–July, made a guest star appearance on The Simpsonsin February,[165][166] was visited by Lady Gaga in October,[167] and Cypherpunks[43] was published in November. In the same year, he analysed the Kissinger cables held at the U.S. National Archives and released them in searchable form.[168][169] On 15 September 2014, he appeared via remote video link on Kim Dotcom's Moment of Truth town hall meeting held in Auckland.[170]

In April 2015, during a video conference to promote the documentary Terminal F about Edward Snowden, Bolivia's ambassador to Russia, María Luisa Ramos Urzagaste, accused Assange of putting the life of Bolivian president Evo Morales at risk by—as Assange reveals in the documentary—intentionally providing to the United States false rumors that Snowden was on the president's plane when it was forced to land in Vienna in July 2013. "It is possible that in this wide-ranging game that you began my president did not play a crucial role, but what you did was not important to my president, but it was to me and the citizens of our country. And I have faith that when you planned this game you took into consideration the consequences," the ambassador told Assange. Assange stated that the plan "was not completely honest, but we did consider that the final result would have justified our actions. We weren't expecting this outcome. The result was caused by the United States' intervention. We can only regret what happened."[171]

On July 3rd, 2015, in the context of an earlier statement by Christiane Taubira[172], Julian Assange requested asylum from France[173]. The request was rejected on the same day by the French presidency in a public statement[174].

Writings

Assange is an advocate of information transparency and "market libertarianism."[175] He has written a few short pieces, including "State and terrorist conspiracies" (2006),[176] "Conspiracy as governance" (2006),[177] "The hidden curse of Thomas Paine" (2008),[178] "What’s new about WikiLeaks?" (2011),[179] and the foreword to Cypherpunks (2012).[43] He also contributed research to Suelette Dreyfus's Underground (1997),[20] and received a co-writer credit for the Calle 13 song "Multi_Viral" (2013).

Cypherpunks is primarily a transcript of the The World Tomorrow episode eight two-part interview between Assange, Jacob Appelbaum, Andy Müller-Maguhn, and Jérémie Zimmermann.

Assange's book When Google Met WikiLeaks was published by OR Books on 18 September 2014.[180] The book recounts when Google CEO Eric Schmidt requested a meeting with Assange, while he was under house arrest in rural Norfolk, UK. Schmidt was accompanied by Jared Cohen, director of Google Ideas; Lisa Shields, vice president of the Council on Foreign Relations; and Scott Malcomson, the communications director for the International Crisis Group. Excerpts were published on the Newsweek website, while Assange participated in a Q&A event that was facilitated by the Reddit website and agreed to an interview with Vogue magazine.[181][182][183]

Personal life

While still in his teens, Assange married a woman known only as Teresa, and in 1989 they had a son, Daniel Assange, now a software designer.[7][19][184] The couple separated and fought over custody of the child until they worked out a custody agreement in 1999.[8]Assange was Daniel's primary caregiver for much of his childhood.[185] For a time he was the partner of WikiLeaks journalist Sarah Harrison.[15][186]

Works about Assange

| Wikinews has news related to: |

Books

- Nick Cohen, You Can't Read this Book: Censorship in an Age of Freedom (2012).

- Suelette Dreyfus, Underground: Tales of Hacking, Madness and Obsession on the Electronic Frontier (1997), with research by Julian Assange.

- Andrew Fowler, The Most Dangerous Man in the World: The Explosive True Story of Julian Assange and the Lies, Cover-ups and Conspiracies He Exposed (2011).

- David Leigh and Luke Harding, WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange's War on Secrecy (2011).

- Andrew O'Hagan, Julian Assange: The Unauthorised Autobiography (2011).

Essays

- Raffi Khatchadourian, "No secrets: Julian Assange's mission for total transparency," The New Yorker, 7 June 2010.

- Robert Manne, "The cypherpunk revolutionary: Julian Assange," The Monthly, March 2011. Reprinted in Robert Manne, Making Trouble: Essays Against the New Australian Complacency (Melbourne: Black Inc. Publishing, 2011).

- Andrew O'Hagan, "Ghosting: Julian Assange," London Review of Books, vol. 36, no. 5 (6 March 2014).

Films

- Underground: The Julian Assange Story (2012), Australian TV drama that premiered at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival.

- Julian (2012), Australian short film about nine-year-old Julian Assange. The film won several awards and prizes.

- The Fifth Estate (2013), thriller.

- Mediastan (2013), documentary produced by Assange; to challenge that of The Fifth Estate.

- We Steal Secrets: The Story of WikiLeaks (2013), American documentary.

Bibliography

- When Google Met WikiLeaks (2014) OR Books

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered