André Malraux

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| André Malraux | |

|---|---|

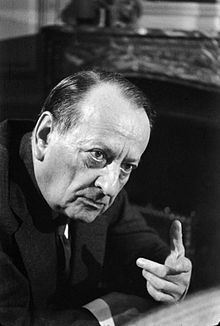

André Malraux in 1974

|

|

| Born | 3 November 1901 Paris, France |

| Died | 23 November 1976 (aged 75) Créteil, France |

| Occupation | Author, statesman |

| Citizenship | French |

| Notable works | La Condition Humaine (Man's Fate) (1933) |

| Notable awards | Prix Goncourt |

| Spouse | Clara Goldschmidt, Josette Clotis, Marie-Madeleine Lioux |

| Children | Florence, Pierre-Gauthier, Vincent |

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

| Portals |

Contents

Early years

Malraux was born in Paris in 1901, the son of Fernand-Georges Malraux and Berthe Lamy (Malraux). His parents separated in 1905 and eventually divorced. There are suggestions that Malraux's paternal grandfather committed suicide in 1909.[1]Malraux was raised by his mother, maternal aunt Marie and maternal grandmother, Adrienne Lamy-Romagna, who had a grocery store in the small town of Bondy.[1][2] His father, a stockbroker, committed suicide in 1930 after the international crash of the stock market and onset of the Great Depression.[3] From his childhood, associates noticed that André had marked nervousness and motor and vocal tics. The recent biographer Olivier Todd, who published a book on Malraux in 2005, suggests that he had Tourette's syndrome, although that has not been confirmed.[4] Either way, most critics have not seen this as a significant factor in Malraux's life or literary works.

The young Malraux left formal education early, but he followed his curiosity through the booksellers and museums in Paris, and explored its rich libraries as well.

Marriage and family

In 1922, Malraux married Clara Goldschmidt. Malraux and his first wife separated in 1938 but didn't divorce until 1947. His daughter from this marriage, Florence (b. 1933), married the filmmaker Alain Resnais.[5]After the breakdown of his marriage with Clara, Malraux lived with journalist and novelist Josette Clotis, starting in 1933. Malraux and Josette had two sons: Pierre-Gauthier (1940–1961) and Vincent (1943–1961). During 1944, while Malraux was fighting in Alsace, Josette died, aged 34, when she slipped while boarding a train. His two sons died together in 1961 in an automobile accident.

In 1948, Malraux married a second time, to Marie-Madeleine Lioux, a concert pianist and the widow of his half-brother, Roland Malraux. They separated in 1966.

Subsequently, Malraux lived with Louise de Vilmorin in the Vilmorin family château at Verrières-le-Buisson, Essonne, a suburb southwest of Paris. Vilmorin was best known as a writer of delicate but mordant tales, often set in aristocratic or artistic milieu. Her most famous novel was Madame de..., published in 1951, which was adapted into the celebrated film The Earrings of Madame de... (1953), directed by Max Ophüls and starring Charles Boyer, Danielle Darrieux and Vittorio de Sica. Vilmorin's other works included Juliette, La lettre dans un taxi, Les belles amours, Saintes-Unefois, and Intimités. Her letters to Jean Cocteau were published after the death of both correspondents. After Louise's death, Malraux spent his final years with her relative, Sophie de Vilmorin.

Career

Early years

Malraux's first published work, an article entitled "The Origins of Cubist Poetry", appeared in the magazine Action in 1920. This was followed in 1921 by three semi-surrealist tales, one of which, "Paper Moons", was illustrated by Fernand Léger. Malraux also frequented the Parisian artistic and literary milieux of the period, meeting figures such as Demetrios Galanis, Max Jacob, François Mauriac, Guy de Pourtalès, André Salmon, Jean Cocteau, Raymond Radiguet, Florent Fels, Pascal Pia, Marcel Arland, Edmond Jaloux, and Pierre Mac Orlan.[6]Indochina

In 1923, aged 22, Malraux left for Cambodia with Clara.[7] There, together with Clara and a friend, Louis Chevasson, he undertook a small expedition into unexplored areas of the Cambodian jungle in search of lost Khmer temples, hoping to recover items that might be sold to art museums. On his return, he was arrested by French colonial authorities for removing a bas-relief from Banteay Srei (a somewhat ironic turn of events[citation needed] given that French authorities had themselves removed large numbers of statues and bas-reliefs from temples such as Angkor Wat). Malraux, who believed he had acted within the law as it then stood, contested the charges but was unsuccessful.[8]Malraux's experiences in Indochina led him to become highly critical of the French colonial authorities there. In 1925, with Paul Monin,[9] a progressive lawyer, he helped to organize the Young Annam League and founded a newspaper L'Indochine.[10]

On his return to France, Malraux published The Temptation of the West (1926). The work was in the form of an exchange of letters between a Westerner and an Asian, comparing aspects of the two cultures. This was followed by his first novel The Conquerors (1928), and then by The Royal Way (1930) which reflected some of his Cambodian experiences.[11] In 1933 Malraux published Man's Fate (La Condition Humaine), a novel about the 1927 failed Communist rebellion in Shanghai. The work was awarded the 1933 Prix Goncourt.[12]

Spanish Civil War

During the 1930s, Malraux was active in the anti-fascist Popular Front in France. At the beginning of the Spanish Civil War he joined the Republican forces in Spain, serving in and helping to organize the small Spanish Republican Air Force.[13] (Curtis Cate, one of his biographers, claims that Malraux was slightly wounded twice during efforts to stop the Falangists' takeover of Madrid, but the historian Hugh Thomas claims otherwise.)The French government sent aircraft to Republican forces in Spain, but they were obsolete by the standards of 1936. They were mainly Potez 540 bombers and Dewoitine D.372 fighters. The slow Potez 540 rarely survived three months of air missions, moving some 80 knots against enemy fighters flying at more than 250 knots. Few of the fighters proved to be airworthy, and they were delivered intentionally without guns or gunsights. (The Ministry of Defense of France had feared that modern types of planes would easily be captured by the Germans fighting for Francisco Franco, and the lesser models were a way of maintaining official "neutrality".)[14] The planes were surpassed by more modern types introduced by the end of 1936 on both sides.

The Republic circulated photos of Malraux standing next to some Potez 540 bombers suggesting that France was on their side, at a time when France and the United Kingdom had declared official neutrality. But Malraux's commitment to the Republicans was personal, like that of many other foreign volunteers, and there was never any suggestion that he was there at the behest of the French Government. Malraux himself was not a pilot, and never claimed to be one, but his leadership qualities seem to have been recognized because he was made Squadron Leader of the 'España' squadron. Acutely aware of the Republicans' inferior armaments, of which outdated aircraft were just one example, he toured the United States to raise funds for the cause. In 1938 he published L'Espoir (Man's Hope), a novel influenced by his Spanish war experiences.[15]

Malraux's participation in major historical events such as the Spanish Civil War inevitably brought him determined adversaries as well as strong supporters, and the resulting polarization of opinion has colored, and rendered questionable, much that has been written about his life. Fellow combatants praised Malraux's leadership and sense of camaraderie,[16] although Antony Beevor says he was criticized by the representative of the Comintern who described him as an "adventurer" for his high profile and demands on the Spanish Republican government. (This criticism is not surprising, however, since the Comintern regularly criticized anyone who did not toe the party line, and despite his support for the Republicans, Malraux was never a member of the Communist Party.)[17] Antony Beevor also claims that "Malraux stands out, not just because he was a mythomaniac in his claims of martial heroism – in Spain and later in the French Resistance – but because he cynically exploited the opportunity for intellectual heroism in the legend of the Spanish Republic."[17] These statements are, however, very questionable since Malraux nowhere makes "claims of martial heroism". In fact, he rarely wrote about his own military experience and when he did (e.g. in his Antimemoirs) placed very little emphasis on his own role.

As a general comment it is worth adding that Malraux's participation in events such as the Spanish Civil War has tended to distract attention from his important literary achievement. Malraux saw himself first and foremost as a writer and thinker (and not "man of action" as biographers so often portray him) but his extremely eventful life – a far cry from the stereotype of the French intellectual confined to his study or a Left Bank café – has tended to obscure this fact. As a result, his literary works, including his important works on the theory of art, have received less attention than one might expect, especially in Anglophone countries.[18]

World War II

At the beginning of the Second World War, Malraux joined the French Army. He was captured in 1940 during the Battle of France but escaped and later joined the French Resistance.[19] In 1944, he was captured by the Gestapo.[20] He later commanded the tank unit Brigade Alsace-Lorraine in defence of Strasbourg and in the attack on Stuttgart.[21]After the war, Malraux was awarded the Médaille de la Résistance and the Croix de guerre. The British awarded him the Distinguished Service Order, for his work with British liaison officers in Corrèze, Dordogne and Lot. After Dordogne was liberated, Malraux led a battalion of former resistance fighters to Alsace-Lorraine, where they fought alongside the First Army.[22]

During the war, he worked on his last novel, The Struggle with the Angel, the title drawn from the story of the Biblical Jacob. The manuscript was destroyed by the Gestapo after his capture in 1944. A surviving first section, titled The Walnut Trees of Altenburg, was published after the war.

After the war

U.S. President John F. Kennedy, Marie-Madeleine Lioux, André Malraux, U.S. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, and U.S. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson at an unveiling of the Mona Lisa at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Mrs. Kennedy described Malraux as "the most fascinating man I've ever talked to".[23]

When de Gaulle returned to the French presidency in 1958, Malraux became France's first Minister of Cultural Affairs, a post he held from 1958 to 1969. Among many initiatives, he launched an innovative (and subsequently widely-imitated) program to clean the blackened facades of notable French buildings, revealing the natural stone underneath.[24] He also created a number of maisons de la culture in provincial cities and worked to preserve France's national heritage.

In 1957, Malraux published the first volume of his trilogy on art entitled The Metamorphosis of the Gods. The second two volumes (not yet translated into English) were published shortly before he died. They are entitled L’Irréel and L'Intemporel and discuss artistic developments from the Renaissance to modern times. Malraux also initiated the series Arts of Mankind, an ambitious survey of world art that generated more than thirty large, illustrated volumes.

Malraux was an outspoken supporter of the Bangladesh liberation movement during the 1971 Pakistani Civil War and despite his age seriously considered joining the struggle.

During this post-war period, Malraux also published a series of semi-autobiographical works, the first entitled Antimémoires (1967). A later volume in the series, Lazarus, is a reflection on death occasioned by his experiences during a serious illness. La Tête d'obsidienne (1974) (translated as Picasso's Mask) concerns Picasso, and visual art more generally.

Malraux died in Créteil, near Paris, on 23 November 1976. He was buried in the Verrières-le-Buisson (Essonne) cemetery. In recognition of his contributions to French culture, his ashes were moved to the Panthéon in Paris during 1996, on the twentieth anniversary of his passing.

Legacy and honours

- 1933, Prix Goncourt

- Médaille de la Résistance

- Croix de guerre

- Distinguished Service Order (United Kingdom)

- 1968, an international Malraux Society was founded in the United States. It produces the journal Revue André Malraux Review, Michel Lantelme, editor, at University of Oklahoma.[27]

- Another international Malraux association, the Amitiés internationales André Malraux, is based in Paris.

- A French-language website, Site littéraire André Malraux,[28] offers a valuable source of research and information about Malraux's works and critical commentary.

Quotations

"Man is dead, after God". Malraux, The Temptation of the West. (1926)‘The artist is not the transcriber of the world, he is its rival.’ Malraux, L'Intemporel (3rd volume of The Metamorphosis of the Gods.)

'In a world in which everything is subject to the passing of time, art alone is both subject to time and yet victorious over it'. Malraux in a television program about art, 1975.

"Art is an object lesson for the gods." The Voices of Silence

"The art museum is one of the places that give us the highest idea of man." The Voices of Silence

"Humanism does not consist in saying: ‘No animal could have done what I have done,’ but in declaring: ‘We have refused what the beast within us willed to do, and we seek to reclaim man wherever we find that which crushes him.’" The Voices of Silence

"The greatest mystery is not that we have been flung at random between this profusion of matter and the stars, but that within this prison we can draw from ourselves images powerful enough to deny our nothingness." Les Noyers de l'Altenburg

Bibliography

- Lunes en Papier, 1923 (Paper Moons, 2005)

- La Tentation de l'Occident, 1926 (The Temptation of the West, 1926)

- Royaume-Farfelu, 1928 (The Kingdom of Farfelu, 2005)

- Malraux, André (1928). Les Conquérants (The Conquerors). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50290-8. (reprint University of Chicago Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-226-50290-8)

- La Voie royale, 1930 (The Royal Way or The Way of the Kings, 1930)

- La Condition humaine, 1933 (Man's Fate, 1934)

- Le Temps du mépris, 1935 (Days of Wrath, 1935)

- L'Espoir, 1937 (Man's Hope, 1938)

- Malraux, André (1948). Les Noyers de l'Altenburg (The Walnut Trees of Altenburg). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50289-2. (reprint University of Chicago Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-226-50289-2)

- La Psychologie de l'Art, 1947–1949 (The Psychology of Art)

- Le Musée imaginaire de la sculpture mondiale (1952–54) (The Imaginary Museum of World Sculpture (in three volumes))

- Les Voix du silence, 1951 (The Voices of Silence, 1953)

- La Métamorphose des dieux (English translation: The Metamorphosis of the Gods, by Stuart Gilbert):

- Vol 1. Le Surnaturel, 1957

- Vol 2. L'Irréel, 1974

- Vol 3. L'Intemporel, 1976

- Antimémoires, 1967 (Anti-Memoirs, 1968 – autobiography)

- Les Chênes qu'on abat, 1971 (Felled Oaks or The Fallen Oaks)

- Lazare, 1974 (Lazarus, 1977)

- L'Homme précaire et la littérature, 1977

- Saturne: Le destin, l'art et Goya, (Paris: Gallimard, 1978) (Translation of an earlier edition published in 1957: Malraux, André. * Saturn: An Essay on Goya. Translated by C.W. Chilton. London: Phaidon Press, 1957.)

- Lettres choisies, 1920–1976. Paris, Gallimard, 2012.

References

- "Biographie détaillée", André Malraux Website, accessed 3 Sep 2010

- Cate, p. 4

- Cate, p. 153

- Katherine Knorr (31 May 2001). "Andre Malraux, the Great Pretender". The New York Times.

- Cate, pp. 388–389

- Biographie détaillée. Malraux.org. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- Cate, pp. 53–58

- Hierarchies of value at Angkor Wat | Lindsay French. Academia.edu. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- Yves Le Jariel, L'ami oublié de Malraux en Indochine, Paul Monin (1890-1929)

- Cate, pp. 86–96

- Cate, p. 159

- Cate, pp. 170–181

- Cate, pp. 228–242

- Cate, p. 235

- John Sturrock (9 August 2001). "The Man from Nowhere". The London Review of Books 23 (15).

- Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure, André Malraux's Theory of Art (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009). pp. 25–27.

- Beevor, p. 140

- Derek Allan, "Art and the Human Adventure, André Malraux's Theory of Art" (Rodopi, 2009)

- Cate, pp. 278–287

- Cate, pp. 328–332

- Cate, pp. 340–349

- "Recommendations for Honours and Awards (Army)—Malraux, Andre" (fee usually required to view full pdf of original recommendation). DocumentsOnline. The National Archives. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- Scott, Janny (11 September 2011). "In Oral History, Jacqueline Kennedy Speaks Candidly After the Assassination". The New York Times.

- Chilvers, Ian. Entry for AM in The Oxford Dictionary of Art (Oxford, 2004). Accessed on 6/28/11 at: http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Andre_Malraux.aspx#4

- Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure: André Malraux's Theory of Art, Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009, p. 21

- Derek Allan. Art and Time, Cambridge Scholars: 2013

- ''Revue André Malraux Review''. Revueandremalraux.com. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- Site littéraire André Malraux. Malraux.org. Retrieved on 1 August 2014.

- This article incorporates information from the revision as of 2010-02-5 of the equivalent article on the French Wikipedia.

Further reading

- Art and the Human Adventure: André Malraux's Theory of Art (Amsterdam, Rodopi: 2009) Derek Allan

- André Malraux (1960) by Geoffrey H. Hartman

- André Malraux: The Indochina adventure (1960) by Walter Langlois (New York Praeger).

- Malraux, André (1976). Le Miroir des Limbes. Bibliothèque de la Pléiade (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-010864-3.

- Malraux (1971) by Pierre Galante (SBN 40212441-3)

- André Malraux: A Biography (1997) by Curtis Cate Fromm Publishing (ISBN 208066795)

- Malraux ou la Lutte avec l'ange. Art, histoire et religion (2001) by Raphaël Aubert (ISBN 2-8309-1026-5)

- Malraux : A Life (2005) by Olivier Todd (ISBN 0375407022) Review by Christopher Hitchens

- Dits et écrits d'André Malraux : Bibliographie commentée (2003) by Jacques Chanussot and Claude Travi (ISBN 2-905965-88-6)

- André Malraux (2003) by Roberta Newnham (ISBN 9781841508542)

- David Bevan (1986). André Malraux: towards the expression of transcendence. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-0552-0.

- Jean François Lyotard (1999). Signed, Malraux. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3106-3.

- Geoffrey T. Harris (1996). André Malraux: a reassessment. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-12925-5.

- Antony Beevor (2006). The battle for Spain: the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303765-1.

- Andre Malraux: Tragic Humanist (1963) by Charles D. Blend, Ohio State University Press (Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 62-19865)

- Derek Allan, Art and Time, Cambridge Scholars, 2013.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered