The Atlantic

Springtime in Tiananmen Square, 1989

Springtime in Tiananmen Square, 1989

While teaching English in Beijing, I witnessed one of the most tumultuous protests in modern history.

Kate Phillips

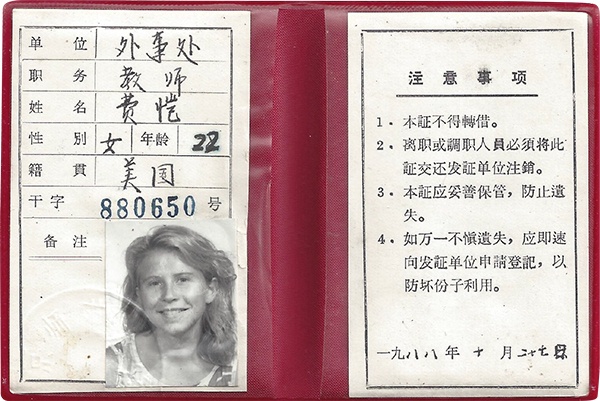

I had just graduated from Dartmouth College and was participating in the school’s one-year teacher-exchange program with Beijing Normal University. I was interested in writing and perhaps becoming a foreign correspondent, planning to publish articles while I worked and bicycled my way around the globe for several years with my boyfriend, Peter, who’d arranged a job at a different university in Beijing.

My teaching at Beijing Normal, or Beishida, was the bright spot in my dreary daily life. I was assigned to instruct Beishida professors from a wide variety of fields and also a few local professionals, who’d all competed for the opportunity to study with a native English speaker. At 22, I was younger than my students, in some cases by 20 years, and a good deal greener. They were formidably smart: three would go on the following year to positions at Oxford and Berkeley. Some laughed at my inexperience, not unkindly; a few complained to my director, Mr. Wu. At one of our first Wednesday teacher meetings, Mr. Wu, a short, twitchy man in his mid-50s, stretched his lips into a thin smile and told me I needed to exercise better “self-control” in front of my students. My explanations, he said, were too long. Soon afterward, he criticized my manner of conducting oral presentations. I’d been careful to give every student a chance to speak, but Mr. Wu said only the best students should be allowed to talk. This would “encourage” the bad ones, he said, and not waste anybody’s time.

During the second week of Advanced Composition, a solemn student, the government-mandated “class monitor,” raised her hand in the middle of my lecture and said, “Miss Kate, we are all wonder, why do you wear so many bracelets?” These were banged-up, two-dollar metal trinkets I’d picked up on backpacking trips to Morocco and Central America, yet she seemed to think I was inappropriately flamboyant. None of my students wore Mao suits anymore but they all dressed very conservatively. I scanned the classroom: Everyone was waiting eagerly for my response. I widened my eyes and said, “Because I like them,” and a few of the younger professors tittered.

As time passed, an atmosphere of playful camaraderie developed in my classes. For my students, too, our sessions offered a welcome departure from regular life. Together, we clowned around in celebration on the day China’s population officially hit the one-billion mark. At the Mid-Autumn Festival, we held a dance party where I refused repeated requests to demonstrate disco and breakdancing, both newly legalized in Beijing, before finally giving in to demands that I sing a Chinese children’s song. One of my older students was obsessed with the ancient medical art of qigong, a kind of breathing exercise, and after class he often entertained us all by attempting, unsuccessfully, to put me into a spiritual trance.

I set up a special Advanced Reading group that met for lively discussions over lunch at one or another of the school cafeterias. These were dirty, overcrowded places, rancid with the smell of undergraduates who exercised every day, were afforded showers only once a week, and lived six to a tiny room. The cafeterias served passable concoctions of tofu and cabbage, along with huge, disgusting vats of rice gruel that was slopped out by the ladleful as you waited in line with the bowl and spoon you had to bring from home. It made for a scene out of the novels of Charles Dickens, one of our group’s favorite authors. One day, in the middle of a conversation about F. Scott Fitzgerald, a student to whom I’d given the English name “Ginny”—a beautiful, married teacher in her mid-20s—plucked a ladybug from her gruel and flicked it on the floor. She rolled her eyes at me. A few years earlier, she said, a student had found a mouse in his rice. There had been a protest, and conditions in the cafeterias had improved—for three days.Like young women everywhere, Ginny and I bonded by way of commiseration. I soon found another ready friend among my students: Olivia, a literary-minded 26-year-old who’d been assigned a dull newspaper job at the university, and now, having reached the commonly accepted age limit for marriageability, was feeling pressure to settle down. A third friend, Feng Ying, was not in my classes, but a graduate student in the psychology department. On our long walks together, Feng Ying told me how her studies were helping her make sense of an almost unbearably fraught childhood, during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76, when millions of Chinese were killed, imprisoned, or relocated in Mao Zedong’s crazed attempts at communist purification. Feng Ying had secretly been obsessed with the phrase “Down with Mao!” and afraid to fall asleep every night, lest those words escape from her dreams and bring ruin upon her family.

More unexpected was the growing trust placed in me by students I didn’t know well. Many seemed eager to share their deepest hopes and disappointments under the cover of English. Two things stood out in what they shared: They were far more disappointed than hopeful, and they were fed up with feeling that way. Their frustration was compounded by material want, to be sure, but their yearning for a better life extended beyond the mere desire for personal advancement. Beneath their many complaints lingered the shadow of idealism—a sense that the political situation in their country should, and even might, change for the better. In retrospect, I know their simmering restlessness was shared by students and professors across Beijing’s campuses, and it would soon come to a boil.

Professors at Beishida had a standard of living just one step above the squalid norm for undergraduates. Tyrannical university administrators controlled every aspect of life. Salaries were so low that many instructors couldn’t afford necessary books or lab equipment, and even married faculty often lived together in dorm rooms with several roommates. My students regularly asked me why, given the freedom I enjoyed to choose my profession, I’d decided to become a teacher in China. They were grateful, in one sense, but they thought I’d been foolhardy.

Older students who’d suffered as adolescents through the Cultural Revolution found any excuse to write about that nightmare. Although its negative repercussions were still reverberating, the Cultural Revolution had been officially denounced, so it provided the perfect subterfuge for expressing ongoing disaffection. In an assigned paragraph about “The Person I Most Admire,” for instance, which I copied into my journal, one middle-aged office worker found occasion to confess:

When I was young, I admired the Monkey King [a famous character in Chinese literature]. When I was a teenager, Chairman Mao was our God. I was a Red Guard. During the Cultural Revolution, Chairman Mao became a human. Now I believe in nothing. Nothing matters to me. So I no longer admire anyone, except my own son.The younger faculty members were less resigned. By December of 1988, a handful of them had grown surprisingly direct in expressing their political dissent and their desire for reform. Gregory, a boyish philosophy professor with an easy laugh and a smattering of stubble on his cheeks, sometimes told anti-government jokes in the minutes before class began. If I asked him to use a word like “ineffective” out loud in a sentence, he’d usually work in the name of China’s paramount leader Deng Xiaoping. He even wrote down his best barbs, turning mundane assignments into brave little acts of defiance. Here, for example, was his take on the ordinary thank-you note:

Dear Sir Xiao-ping Deng,I shared some of their gloom, especially during the winter. It was bitterly cold, and on Tuesdays and Fridays the heat and electricity were shut off in my classroom as part of a campus-wide effort to save energy. Everywhere I went, people hacked up gobs of phlegm and spat them on the ground. I was repeatedly sick with respiratory infections and fevers, and then my hair began to fall out in big clumps, the result of what was eventually diagnosed as malnutrition and stress. My problems weren’t only physical. My relationship with Peter was also falling apart. We’d moved halfway around the world together and made idyllic plans for years of joint travel and work, so we were having trouble recognizing a painful reality that would change everything: We weren’t really in love anymore. “You want melodrama,” Peter told me one night. “You need ups and downs, or else the ups don’t feel great. I’m not like that and I don’t want to be.” His reasonableness was infuriating.

My hopes were shattered one by one since you have become the top leader of this country. I have no house, little money and low position. But I used to desire a personal car! I really thank you for this. It is said: the more poor a person is, the more noble. Perhaps you want us teachers to be more noble.

Thank you very much.

As spring approached, politics overtook my private turmoil, bringing a welcome release. On Saturday, April 15, Hu Yaobang—a controversial government official who had been admired by many students for his stands against corruption, government secrecy, and economic rigidity—died of a heart attack. Students at Beishida and other universities held “mourning” activities—disguised protests—in honor of his death. On Monday night, I went to view a memorial in one of the graduate student buildings. Later, at 1 a.m., I was awakened back in my room by some 500 Beihang University students marching down the street below shouting, “Beishida—come out with us!” They were headed to Tiananmen Square. But our students were locked inside the university gates, guarded by two official student political leaders.

Protests soon broke out all over the city. Students stayed in Tiananmen Square all night. After teaching on Wednesday, I took the subway seven miles southeast to the Square and got there around noon, just as 300 to 400 Beijing University students also arrived, having walked over 10 miles from their campus. They marched triumphantly to the central Monument to the People’s Heroes, where they joined thousands of other students in laying funeral wreaths and unfurling red banners.

The government’s response to all these activities was strangely muted. On Thursday, students went “on strike” at all the major universities across Beijing. Since my own students were professors, only one of them participated in the boycott, and only for a day. They continued to show up for class, even as normal undergraduate instruction became sporadic. Their presence allowed me to gauge evolving sentiment in the city. Some of my older students couldn’t bear the thought of yet another political upheaval interfering with their English education. They stared at me stone-faced and insisted that I continue with our grammar lessons, conversation drills, and spelling tests. Other, younger professors wanted only to talk about what was happening and exchange information. Gregory arrived breathless to class on Thursday, explaining that he’d followed a group of students on their way to the Square that morning, only to have them disappear before his very eyes. He suspected they had been waylaid by the police and secretly taken into custody. “What does the government want to do?” he later wrote in an assignment. “We worry over [the students’] safety. We love them.”

At the Square, we found some 100,000 people. Suddenly, I was scared. Not of the crowd, not in the least—but of how the government was going to react. It was midnight. A nerve-fraying electricity filled the air: unprecedented euphoria, mixed with dread. Something would have to happen before all these people would go home.

For seven weeks, the protests around Tiananmen Square continued unabated. Many of the people who filled the streets in the later days were not students but reform-minded citizens. For such a huge, motley assembly, the protesters were remarkably peaceful and unified. A charismatic 21-year-old from Beishida, Wu’er Kaixi, gave tearful, impassioned speeches, and became one of the main student leaders in the Square. (The names of all Chinese people in this essay have been changed with the exception of political figures and Wu’er Kaixi, who is currently exiled in Taiwan.)

In the second week of May, an acquaintance helped Peter and me get jobs at ABC. Like other foreign television networks, ABC was scrambling to prepare for Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s visit to Beijing on May 15, for the first Sino-Soviet summit in 30 years. The networks were hiring young expats to work as interpreters, production assistants, and all-around grunts. I signed up, excited to get a taste of life as a foreign correspondent and to earn some much-needed extra money. Every weekday, after teaching in the morning, I rode my bike 45 minutes east across the northern part of town to the Great Wall Sheraton, ABC’s temporary headquarters, to work for another 10 or 11 hours. On weekends, I worked and slept at the hotel.

On May 13, two days before Gorbachev arrived, the headlines changed. Students in the Square began a hunger strike intended to divert the attention of the international media, disrupt the summit, and humiliate the government. The crowd around the Square peaked at an astonishing 1 million people.In just a few short days, the jubilation of the previous weeks collapsed. On one of the increasingly rare nights when I slept at my dorm instead of hurrying back from ABC just before teaching in the morning, I watched in horror from my balcony as military trucks carrying soldiers standing at attention and giant black water cannons rolled down Xinjiekouwai. There were no more chanting marchers. Instead, a steady stream of courageous volunteer doctors and nurses in white jackets trickled down the street on bicycles with hastily made red crosses dangling from the handlebars, en route to help the hunger strikers. Their tinkling bells rang all night long, occasionally making their way into my dreams. Then one night, in the final week of May, I heard ambulance sirens wailing every few minutes, as the starving students began to collapse.

On Thursday night, June 1, I went to the Square for the last time, accompanying an ABC cameraman as a hauler and interpreter. That whole week, I’d been frustrated that only young men were being given this dangerous duty; I’d insisted that women were equally capable and that I deserved a chance. But now, faced with the near certainty of an impending crackdown, I was unnerved. I was having trouble understanding my role in another country’s politics. I revered the work of fabled correspondents like Martha Gellhorn, who had taken a stand against despotism in foreign lands including this one; I knew that the struggle for human rights in the world’s most populous country was a matter that transcended borders. But I didn’t want to risk my life to witness it.

I was that scared. I didn’t know my way around the Square’s dark side streets. In recent days, a rumor had been circulating that the army was waiting underground in the vast network of tunnels that runs beneath much of Beijing, and that at any moment troops were going to burst out unexpectedly from the mouths of the subway. The cement grounds of Tiananmen Square, so recently pulsing with the hopes and dreams of a not-yet-jaded generation, seemed poised to swallow us all up.

The crowd in the Square had shrunk dramatically as disorder and confusion had grown. There was infighting among the student leaders, and people accused them of corruption. Exhausted from the hunger strike and fearing the worst, students had begun abandoning the protest camp. Some of those still present had come to Beijing belatedly from other parts of the country after news of the demonstration had reached them, and they didn’t necessarily share the lofty ideals of the original participants. In some places I ventured that Thursday night, there was a raucous party atmosphere. I saw onlookers drinking beer, shouting, and blasting music from boom boxes. Around 3 a.m., a pickup truck passed far too close to me, carrying several young working men dressed in blue jumpsuits in the back. They were drunk. “Hey, get in!” they shouted to me. “Let’s go play!”

It was a massacre. Most of the carnage occurred not in the Square or right around it, but in the western-approaching streets that led to the Square. I viewed the videotapes of bloody bodies that came in with camera crews, and I made phone calls to local hospitals and to the Chinese Red Cross. We kept a running tally of the number of dead, which had reached 2,600 before everyone was ordered to stop talking to us.

Later on Sunday, the government initiated a whitewashing campaign, insisting that only a handful of civilians had died but that hundreds of soldiers had been beaten to death by rabble-rousers. In the coming days, Chinese television replayed tragic footage of these soldiers’ beatings—in truth, there were probably only a few—alongside clips of interviews with ordinary citizens, stolen from foreign news sources, spliced with captions that read, “This person is a counterrevolutionary. If you know this person, report him immediately.”

On Monday morning, I volunteered to ride my bicycle to ABC’s empty permanent office on Jianguomenwai Street to wait for the Chinese wire service’s report on the events. My journey was stunning. On one block, I’d see children playing in the street, enjoying what might have been any other sunny, tranquil spring day. Then, just a few blocks away, the sky would be filled with black smoke and I’d be surrounded by the smoldering hulls of burnt-out buses and trucks that had been abandoned the previous morning in desperate attempts to block the advancing army.

Bullets were coming toward me, too. I ducked beneath the window, terrified. I told the news desk I needed help getting back to the Sheraton. Next, realizing I had rare access to an international telephone line, I called my mother. When she heard the gunfire, she begged me to come home to Southern California. I agreed that I would leave the country for a while.

That afternoon, a newly hired ABC driver agreed to take me back to my dorm to retrieve my passport and some personal belongings. At one point, a dozen soldiers stopped our car, shoving their rifles up against our windows. When I walked onto the Beishida campus, it was deserted. Those students who could go back to their homes in Beijing had gone. As I approached my dorm, a group of undergraduate girls surrounded me, crying. I didn’t know them. “Are you leaving?” they asked me. “I think so,” I said, trying not to cry myself. The girls said they were from another province, and that they had no place to “hide.” It felt horrible, this unjust disparity between us. But then they smiled at me bravely. “We think you’re smart to go,” one of them said. “Please tell everyone what is happening here.”

Inside the lobby of my building, a dozen Japanese students were gathered around a representative from their embassy, waiting to board a bus to the airport. Someone told me that Mr. Wu had come by frantically that morning, searching for me and the other American teachers. He wanted to warn us to clear out; the dorm was no longer considered safe, and we were all being evicted. I hurried to my room. On the floor, just inside the door, I found a note from my friend Feng Ying. “Kate: Do you know what has happened?” it read. “Two of my friends have been killed. Please tell the world.” I slipped the note into my journal and clutched it tight. I grabbed my passport and left Beishida for good.

On Wednesday, when I was supposed to be hosting a class picnic, I said goodbye to Peter over the phone. I hadn’t seen him in days—he’d been out around the clock with the camera crews—and I would not see him again for many years, not until one quiet afternoon in a Seattle bookstore, when I was engaged to be married, and on a tour for my first book. (By then, my friend Olivia had become a professor in California and settled happily into family life there; we are still friends today.)

Frightened, and with an ABC video duct-taped to my stomach beneath my shirt, I headed to the Beijing airport, which was a madhouse of foreigners trying to get out of the country. I spent the next month drifting around Japan and Thailand, having terrible dreams every night. Although ABC had asked me back, I decided not to return to Beijing. I was exhausted and depressed. I’d learned some difficult lessons about ideals and reality. And I was beginning to comprehend another: I liked the idea of brave, worthwhile action in the world—and trying to honor such action in my writing—much more than I liked trying to be brave myself.