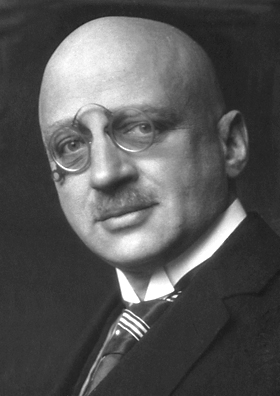

Fritz Haber

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Fritz Haber | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 December 1868 Breslau, Prussia |

| Died | 29 January 1934 (aged 65) Basel, Switzerland |

| Nationality | German |

| Fields | Physical chemistry |

| Institutions | Swiss Federal Institute of Technology University of Karlsruhe |

| Alma mater | University of Heidelberg,Humboldt University of Berlin Technical University of Berlin |

| Doctoral advisor | Robert Bunsen |

| Known for | Haber process Born-Haber cycle Fertilizer Haber–Weiss reaction Chemical warfare Explosives |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1918) Rumford Medal (1932) |

| Spouse | Clara Immerwahr (1901-1915; her death; 1 child) Charlotte Nathan (1917-1927; divorced; 2 children) |

Fritz Haber (German: [ˈhaːbɐ]; 9 December 1868 – 29 January 1934) was a German chemist of Jewish origin who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his development for synthesizing ammonia, important for fertilizers and explosives. The food production for half the world's current population depends on this method for producing fertilizer. Haber, along with Max Born, proposed the Born–Haber cycle as a method for evaluating the lattice energy of an ionic solid.

Notoriously, Haber is also remembered to history as the "father of chemical warfare" for his years of pioneering work developing and weaponizing chlorine and other poisonous gases during World War I, as well as his later founding chairmanship of the Degesch Corporation, which (two decades after Haber's term) knowingly produced the hydrogen cyanide-based Zyklon B gas used to kill millions in the gas chambers of the Holocaust[citation needed].

Contents

[hide]Early life and education[edit]

Fritz Haber was born in Breslau, Prussia (now Wrocław, Poland), into a well-off Jewish family.[1]:38 The family name Haber was a common one in the area, but Fritz Haber's family has been traced back to a great-grandfather, Pinkus Selig Haber, a wool dealer from Kempen. An important Prussian edict of 13 March 1812 determined that Jews and their families, including Pinkus Haber, were "to be treated as local citizens and citizens of Prussia". Under such regulations, members of the Haber family were able to establish themselves in respected positions in business, politics, and law.[2]:3–5

Fritz Haber was the son of Siegfried and Paula Haber, first cousins who married in spite of considerable opposition from their families.[3] Fritz's father Siegfried was a well-known merchant in the town, who had founded his own business in dye pigments, paints and pharmaceuticals.[2]:6 Paula experienced a difficult pregnancy and died three weeks after Fritz's birth, leaving Siegfried devastated and Fritz in the care of various aunts.[2]:11 When Fritz was about 6 years old, Siegfried remarried, to Hedwig Hamburger. Siegfried and his second wife had three daughters, Else, Helene and Frieda. Although his relationship with his father was distant and often difficult, Fritz developed close relationships with his step-mother and his half-sisters.[2]:7

By the time Fritz was born, the Habers had to some extent assimilated into German society. Fritz attended primary school at the Johanneum School, a "simultaneous school" open equally to Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish students.[2]:12 At age 11, he went to school at the St. Elizabeth classical school, in a class evenly divided between Protestant and Jewish students.[2]:14 His family supported the Jewish community and continued to observe many Jewish traditions, but were not strongly associated with the synagogue.[2]:15 Fritz Haber identified strongly as German, less so as Jewish.[2]:15

Fritz Haber successfully passed his examinations at the St. Elisabeth High School in Breslau in September 1886.[2]:16 Although his father wished him to apprentice in the dye company, Fritz obtained his father's permission to study chemistry, at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin (today the Humboldt University of Berlin), with the director of the Institute for Chemistry, A. W. Hofmann.[2]:17 Haber was disappointed by his initial winter semester (1886-1887) in Berlin, and arranged to attend the University of Heidelberg for the summer semester of 1887, where he studied under Robert Bunsen.[2]:18 He then returned to Berlin, to the Technical College of Charlottenburg (today the Technical University of Berlin).[2]:19 In the summer of 1889 he left university to perform a legally required year of voluntary service in the Sixth Field Artillery Regiment.[2]:20 Upon its completion, he returned to Charlottenburg where he became a student of Carl Liebermann. In addition to Liebermann's lectures on organic chemistry, Haber also attended lectures by Otto Witt on the chemical technology of dyes.[2]:21 Liebermann assigned Haber to work on reactions withPiperonal for his thesis topic, published as Über einige Derivate des Piperonals (About a Few Piperonal Derivatives) in 1891.[4] Haber received his doctorate cum laude from Friedrich Wilhelm University in May 1891, after presenting his work to a board of examiners from the University of Berlin, since Charlottenburg was not yet accredited to grant doctorates.[2]:22

With his degree, Fritz returned to Breslau to work at his father's chemical business. They did not get along well. Through Siegfried's connections, Fritz was assigned a series of practical apprenticeships in different chemical companies, to gain experience. These included Grunwaldt and Company (a Budapest distillers), an Austrian ammonia-sodium factory, and the Feldmühle paper and cellulose works. Haber realized, based on these experiences, that he needed to learn more about technical processes, and convinced his father to let him spend a semester at Polytechnic College in Zürich (now the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), studying with Georg Lunge.[2]:27–29 In fall of 1892, Haber returned again to Breslau to work in his father's company, but the two men continued to clash and Siegfried finally accepted that they could not work well together.[2]:30–31

Early career[edit]

Haber then sought an academic appointment, first working as an independent assistant to Ludwig Knorr at the University of Jena between 1892 and 1894.[2]:32 During his time in Jena, Haber converted from Judaism to Lutheranism, possibly in an attempt to improve his chances of getting a better academic or military position.[2]:33 Knorr recommended Haber to Carl Engler,[2]:33 a professor chemistry at the University of Karlsruhe who was intensely interested in the chemical technology of dye and the dye industry, and the study of synthetic materials for textiles.[2]:38 Engler referred Haber to a colleague in Karlsruhe, Hans Bunte, who made Haber an Assistent in 1894.[2]:40[5]

Bunte suggested that Haber examine the thermal decomposition of hydrocarbons. By making careful quantitative analyses, Haber was able to establish that "the thermal stability of the carbon-carbon bond is greater than that of the carbon-hydrogen bond in aromatic compounds and smaller in aliphatic compounds", a classic result in the study of pyrolysis of hydrocarbons. This work became Haber's habilitation thesis.[2]:40

Haber was appointed a Privatdozent in Bunte's institute, taking on teaching duties related to the area of dye technology, and continuing to work on the combustion of gases. In 1896, the university supported him in traveling to Silesia, Saxony, and Austria to learn about advances in dye technology.[2]:41

In 1897 Haber made a similar trip to learn about developments in electrochemistry.[2]:41 He had been interested in the area for some time, and had worked with another privadocent, Hans Luggin, who gave theoretical lectures in electrochemistry and physical chemistry. Haber's 1898 book Grundriss der technischen Elektrochemie auf theoretischer Grundlage (Outline of technical electrochemistry based on theoretical foundations) attracted considerable attention, particularly his work on the reduction of nitrobenzene. In the book's foreword, Haber expresses his gratitude to Luggin, who, sadly, died on 5 December 1899.[2]:42 Haber collaborated with others in the area as well, including Georg Bredig, a student of Wilhelm Ostwald in Leipzig.[2]:43

Bunte and Engler supported an application for further authorization of Haber's teaching activities, and on 6 December 1898, Haber was invested with the title of Extraordinarius and an associate professorship, by order of the Grand Duke Friedrich von Baden.[2]:44

Haber worked in a variety of areas while at Karlsruhe, making significant contributions in several areas. In the area of dye and textiles, he and Friedrich Bran were able to theoretically explain steps in textile printing processes developed byAdolf Holz. Discussions with Carl Engler prompted Haber to explain autoxidation in electrochemical terms, differentiating between dry and wet autoxidation. Haber's examinations of the thermodynamics of the reaction of solids confirmed thatFaraday's laws hold for the electrolysis of crystalline salts. This work led to a theoretical basis for the glass electrode and the measurement of electrolytic potentials. Haber's work on irreversible and reversible forms of electrochemical reductionare considered classics in the field of electrochemistry. He also studied the passivity of non-rare metals[clarification needed] and the effects of electric current on corrosion of metals.[2]:55 In addition, Haber published his second book,Thermodynamik technischer Gasreaktionen : sieben Vorlesungen (1905) trans. Thermodynamics of technical gas-reactions : seven lectures (1908), later regarded as "a model of accuracy and critical insight" in the field of chemical thermodyamics.[2]:56–58

In 1906, Max Le Blanc, chair of the physical chemistry department at Karlsruhe, accepted a position at the University of Leipzig. After receiving recommendations from a search committee, the Ministry of Education in Baden offered the full professorship for physical chemistry at Karlsruhe to Fritz Haber, who accepted the offer.[2]:61

Nobel Prize[edit]

During his time at University of Karlsruhe from 1894 to 1911, Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch developed the Haber–Bosch process, which is the catalytic formation of ammonia from hydrogen and atmospheric nitrogen under conditions of high temperature and pressure.[6] The Haber–Bosch process was a milestone in industrial chemistry. The production of nitrogen-based products such as fertilizer and chemical feedstocks, previously dependent on acquisition of ammonia from limited natural deposits, now became possible using an easily available, abundant base—atmospheric nitrogen.[7] The ability to produce much larger quantities of nitrogen-based fertilizers in turn supported much greater agricultural yields.[8]

The discovery of a new way of producing ammonia had other significant economic impacts as well. Chile had been a major (and almost unique) producer of natural deposits such as sodium nitrate (caliche). After the introduction of the Haber process, naturally extracted nitrate production in Chile fell from 2.5 million tons (employing 60,000 workers and selling at $45/ton) in 1925 to just 800,000 tons, produced by 14,133 workers, and selling at $19/ton in 1934.[9]

The annual world production of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer is currently more than 100 million tons. The food base of half of the current world population is based on the Haber–Bosch process.[8]

Haber was awarded the 1918 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work. (He actually received the award in 1919).[10]

Haber was also active in the research on combustion reactions, the separation of gold from sea water, adsorption effects, electrochemistry, and free radical research (see Fenton's reagent). A large part of his work from 1911 to 1933 was done at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry and Elektrochemistry at Berlin-Dahlem. In 1953, this institute was renamed for him. He is sometimes credited, incorrectly, with first synthesizing MDMA (which was first synthesized by Merck KGaA chemist Anton Köllisch in 1912).[11][12]

World War I[edit]

Haber played a major role in the development of chemical warfare in World War I, in spite of their proscription in the Hague Convention of 1907 (to which Germany was a signatory). He was promoted to the rank of captain and made head of the Chemistry Section in the Ministry of War soon after the war began.[2]:133 In addition to leading the teams developing chlorine gas and other deadly gases for use in trench warfare, Haber was on hand personally when it was first released by the German military at the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April to 25 May 1915) in Belgium.[2]:138 Haber also helped to develop gas masks with adsorbent filters which could protect against such weapons. A special troop was formed for gas warfare (Pioneer Regiments 35 and 36), under the command of Otto Peterson, with Haber and Friedrich Kerschbaum as advisors. Haber actively recruited physicists, chemists, and other scientists to be transferred to the unit. Future Nobel laureatesJames Franck, Gustav Hertz, and Otto Hahn served as gas troops in Haber's unit.[2]:136–138 In 1914 and 1915, before the Second Battle of Ypres, Haber's unit investigated reports that the French had deployed Turpenite, a supposed chemical weapon, against German soldiers.[13]

Gas warfare in World War I was, in a sense, the war of the chemists, with Haber pitted against French Nobel laureate chemist Victor Grignard. Regarding war and peace, Haber once said, "During peace time a scientist belongs to the World, but during war time he belongs to his country." This was an example of the ethical dilemmas facing chemists at that time.[14]

Haber was a patriotic German who was proud of his service during World War I, for which he was decorated.[15] He was even given the rank of captain by the Kaiser, rare for a scientist too old to enlist in military service.

In his studies of the effects of poison gas, Haber noted that exposure to a low concentration of a poisonous gas for a long time often had the same effect (death) as exposure to a high concentration for a short time. He formulated a simple mathematical relationship between the gas concentration and the necessary exposure time. This relationship became known as Haber's rule.

Haber defended gas warfare against accusations that it was inhumane, saying that death was death, by whatever means it was inflicted. During the 1920s, scientists working at his institute developed the cyanide gas formulation Zyklon A, which was used as an insecticide, especially as a fumigant in grain stores.[16]

Personal life and family[edit]

Haber married Clara Immerwahr on 3 August 1901.[2]:46 They met in Breslau in 1889, while Haber was serving his required year in the military. Clara was the daughter of a chemist who owned a sugar factory, and the first woman to earn a PhD at the University of Breslau.[2]:20 She converted to Christianity in 1897, some years before she and Haber became engaged.[2]:46 After their marriage, Clara gave up her career in chemistry, and tried to become the perfect wife.[2]:174 Their son Hermann was born on 1 June 1902.[2]:173 Intelligent and perfectionist, Clara became increasingly depressed. When World War I began, she is believed to have opposed Haber's work in chemical warfare. On 2 May 1915, following an argument with Haber, she committed suicide in their garden by shooting herself in the heart with his service revolver. She did not die immediately, and was found by her 13-year-old son, Hermann, who had heard the shots.[2]:176 It is believed that her suicide may have been in part a response to Haber's having personally overseen the first successful use of chlorine at the Second Battle of Ypres on 22 April 1915.[17][18] Haber left within days for the Eastern Front to oversee gas release against the Russians.[19][20] Originally buried in Daheim, Clara's remains were later transferred at her husband's request to Basel, where she is buried next to him.[2]:176

Haber married his second wife, Charlotte Nathan, on 25 October 1917 in Berlin.[2]:183 Charlotte, like Clara, converted from Judaism to Christianity before marrying Haber.[2]:183 The couple had two children, Eva-Charlotte and Ludwig-Fritz ("Lutz").[2]:186 Again, however, there were conflicts, and the couple were divorced as of 6 December 1927.[2]:188

Between World Wars[edit]

From 1919 to 1923 Haber continued to be involved in Germany's secret development of chemical weapons, working with Hugo Stoltzenberg, and helping both Spain and Russia in the development of chemical gases.[2]:169

In the 1920s, Haber searched exhaustively for a method to extract gold from sea water, and published a number of scientific papers on the subject. After years of research, he concluded that the concentration of gold dissolved in sea water was much lower than those reported by earlier researchers, and that gold extraction from sea water was uneconomic.[1]:91–98

By 1931, Haber was increasingly concerned about the rise of National Socialism in Germany, and the possible safety of his friends, associates, and family. Under the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service of 7 April 1933, Jewish scientists at the Kaiser Wilhelm Society were particularly targeted. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Naturwissenschaft charged that "The founding of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes in Dahlem was the prelude to an influx of Jews into the physical sciences. The directorship of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical and Electrochemistry was given to the Jew F. Haber, the nephew of the big-time Jewish profiteer Koppel". (Koppel was not in fact related to Haber).[2]:277–280 Ordered to dismiss all Jewish personnel, Haber attempted to delay their departures long enough to find them somewhere to go.[2]:285–286 As of 30 April 1933, Haber wrote to Bernhard Rust, the national and Prussian minister of Education, and to Max Planck, president of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, to tender his resignation as the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, and as a professor at the university, effective 1 October 1933. He stated that although, as a converted Jew, he might be legally entitled to remain in his position, he no longer wished to do so.[2]:280

Haber and his son Hermann also urged that Haber's children by Charlotte Nathan, at boarding school in Germany, should leave the country.[2]:181 Charlotte and the children moved to England around 1933 or 1934. After the war, Charlotte's children became English citizens.[2]:188–189

Haber left Dahlem in August 1933, staying briefly in Paris, Spain, and Switzerland. He was in extremely poor health, and suffered what was either a stroke or a heart attack.[2]:288

In the meantime, some of the scientists who had been Haber's counterparts and competitors in England during World War I now helped him and others to leave Germany. Brigadier Harold Hartley, Sir William Jackson Pope and Frederick G. Donnan arranged for Haber to be officially invited to Cambridge, England.[2]:287–288 There, with his assistant Joseph Joshua Weiss, Haber lived and work for a few months.[2]:288 Scientists such as Ernest Rutherford were less forgiving of Haber's involvement in poison gas warfare: Rutherford pointedly refused to shake hands with him.[21]

Death[edit]

In 1933, during Haber's brief sojourn in England, Chaim Weizmann offered him the directorship at the Sieff Research Institute (now the Weizmann Institute) in Rehovot, in Mandatory Palestine. He accepted, and left for the Middle East in January 1934, traveling with his half-sister, Else Haber Freyhahn.[2]:209, 288–289 His ill health overpowered him and on 29 January 1934, at the age of 65, he died of heart failure, mid-journey, in a Basel hotel.[2]:299–300 Following Fritz' wishes, Fritz and Clara's son Hermann arranged for Fritz to be cremated and buried in Basel's Hörnli Cemetery on 29 September 1934, and for Clara's remains to be removed from Dahlem and re-interred with him on 27 January 1937.[2]:300[22] Fritz Haber bequeathed his extensive private library to the Sieff Institute, where it was dedicated as the Fritz Haber Library on 29 January 1936. Hermann Haber helped to move the library and gave a speech at the dedication.[2]:182

Hermann Haber lived in France until 1941, but was unable to obtain French citizenship. When Germany invaded France during World War II, Hermann and his family escaped internment on a French ship travelling from Marseilles to the Caribbean. From there, they obtained visas allowing them to emigrate to the United States. Hermann's wife Margarethe died after the end of the war, and Hermann committed suicide in 1946.[2]:182–183

Several members of Haber's extended family died in concentration camps, including his half-sister Frieda's daughter, Hilde Glücksmann, her husband, and their two children.[2]:235 One of his children,Ludwig ("Lutz") Fritz Haber (1921–2004), became an eminent historian of chemical warfare in World War I and published a book called The Poisonous Cloud (1986).[23]

Awards and Honours[edit]

- Foreign Honorary Member, American Academy of Arts and Sciences(1914)[1]:152[24]

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1918)[5]

- Bunsen Medal of the Bunsen Society of Berlin, with Carl Bosch (1918)[25]

- President of the German Chemical Society (1923)[26]:169

- Honorary Member, Société Chimique de France (1931)[1]:152

- Honorary Member, Chemical Society of England (1931)[1]:152

- Honorary Member, Society of Chemical Industry, London, (1931)[1]:152

- Rumford Medal, American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1932)[27]

- Foreign Associate Member, National Academy of Sciences, USA (1932)[28][29]

- Honorary Member, USSR Academy of Sciences (1932)[1]:152

- Board of Directors, International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, 1929-1933; Vice-President, 1931[2]:271

- Goethe-Medaille für Kunst und Wissenschaft (Goethe Medal for Art and Science) from the President of Germany.[26]

Criticism[edit]

Haber received much criticism for his involvement in the development of chemical weapons in pre-World War II Germany, both from contemporaries and from modern-day scientists.[30] The research results show the ambivalence of his scientific activity: on the one hand, development of ammonia synthesis for the manufacture of explosives and of a technical process for the industrial manufacture and use of poison gas in warfare; but on the other hand, development of an industrial process without which the food supply for today's world population might be greatly diminished.

Dramatic treatment[edit]

A fictional description of Haber's life, and in particular his longtime relationship with Albert Einstein, appears in Vern Thiessen's 2003 play Einstein's Gift. Thiessen describes Haber as a tragic figure who strives unsuccessfully throughout his life to evade both his Jewish ancestry and the moral implications of his scientific contributions.

BBC Radio 4 Afternoon Play has broadcast two plays on the life of Fritz Haber. This is the description of the first[31] from the Diversity Website:

| “ | Bread from the Air, Gold from the Sea as another chemical story (R4, 1415, 16 Feb 01). Fritz Haber found a way of making nitrogen compounds from the air. They have two main uses: fertilizers and explosives. His process enabled Germany to produce vast quantities of armaments. (The second part of the title refers to a process for obtaining gold from sea water. It worked, but didn't pay.) There can be few figures with a more interesting life than Haber, from a biographer's point of view. He made German agriculture independent of Chilean saltpetre during the Great War. He received the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, yet there were moves to strip him of the award because of his work on gas warfare. He pointed out, rightly, that most of Nobel's money had come from armaments and the pursuit of war. After Hitler's rise to power, the government forced Haber to resign from his professorship and research jobs because he was Jewish. | ” |

The second was entitled "The Greater Good" and was first broadcast on 23 October 2008.[32] It was directed by Celia de Wolff and written by Justin Hopper, and starred Anton Lesser as Haber. It explored his work on gas warfare during theFirst World War and the strain it put on his wife Clara (Lesley Sharp), concluding with her suicide and its cover-up by the authorities. Other cast included Dan Starkey as Haber's research associate Otto Sackur, Stephen Critchlow as Colonel Peterson, Conor Tottenham as Haber's son Hermann, Malcolm Tierney as General Falkenhayn and Janice Acquah as Zinaide.

In 2008, a short film entitled Haber depicted Fritz Haber's decision to embark on the gas warfare program and his relationship with his wife.[33] The film was written and directed by Daniel Ragussis.[34][35]

In 2012, Haber was featured on an episode of Dark Matters: Twisted But True.

In December 2013 Haber was the subject of a BBC World Service radio programme: "Why has one of the world's most important scientists been forgotten?".[38]

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered