Michel de Montaigne

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

| Born | Michel Eyquem de Montaigne 28 February 1533 (O.S.) Château de Montaigne |

|---|---|

| Died | 13 September 1592 (aged 59) Château de Montaigne |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| School | Renaissance humanism Renaissance skepticism |

| Notable ideas | The essay, Montaigne's wheel argument |

In his own time, Montaigne was admired more as a statesman than as an author. The tendency in his essays to digress into anecdotes and personal ruminations was seen as detrimental to proper style rather than as an innovation, and his declaration that, 'I am myself the matter of my book', was viewed by his contemporaries as self-indulgent. In time, however, Montaigne would be recognized as embodying, perhaps better than any other author of his time, the spirit of freely entertaining doubt which began to emerge at that time. He is most famously known for his skeptical remark, 'Que sçay-je?' ('What do I know?' in Middle French; modern French Que sais-je?). Remarkably modern even to readers today, Montaigne's attempt to examine the world through the lens of the only thing he can depend on implicitly—his own judgment—makes him more accessible to modern readers than any other author of the Renaissance. Much of modern literary non-fiction has found inspiration in Montaigne and writers of all kinds continue to read him for his masterful balance of intellectual knowledge and personal story-telling.

Contents

Life

Château de Montaigne, a house built on the land once owned by Montaigne's family. His original family home no longer exists, though the tower in which he wrote still stands.

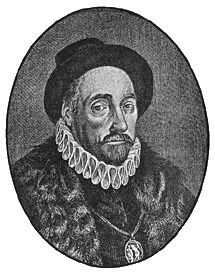

Portrait of Michel de Montaigne by Dumonstier around 1578.

The Tour de Montaigne (Montaigne's tower), mostly unchanged since the 16th century, where Montaigne's library was located

His mother lived a great part of Montaigne's life near him, and even survived him, but is mentioned only twice in his essays. Montaigne's relationship with his father, however, is frequently reflected upon and discussed in his essays.

From the moment of his birth, Montaigne's education followed a pedagogical plan sketched out by his father and refined by the advice of the latter's humanist friends. Soon after his birth, Montaigne was brought to a small cottage, where he lived the first three years of life in the sole company of a peasant family, 'in order to', according to the elder Montaigne, 'draw the boy close to the people, and to the life conditions of the people, who need our help.'[13] After these first spartan years, Montaigne was brought back to the château. The objective was for Latin to become his first language. The intellectual education of Montaigne was assigned to a German tutor (a doctor named Horstanus who couldn't speak French). His father hired only servants who could speak Latin and they also were given strict orders to always speak to the boy in Latin. The same rule applied to his mother, father, and servants, who were obliged to use only Latin words he himself employed, and thus acquired a knowledge of the very language his tutor taught him. Montaigne's Latin education was accompanied by constant intellectual and spiritual stimulation. He was familiarized with Greek by a pedagogical method that employed games, conversation, and exercises of solitary meditation, rather than books.

The atmosphere of the boy's life, although designed by highly refined rules taken under advisement by his father, created in the boy's life the spirit of "liberty and delight", in order to "to make me relish... duty by an unforced will, and of my own voluntary motion... without any severity or constraint;"[14] yet he would have everything in order to take advantage of his freedom. And so a musician woke him every morning, playing one instrument or another,[15] and an épinettier (with a zither) was the constant companion to Montaigne and his tutor, playing a tune to alleviate boredom and tiredness.

Around the year 1539, Montaigne was sent to study at a prestigious boarding school in Bordeaux, the Collège de Guyenne, then under the direction of the greatest Latin scholar of the era, George Buchanan, where he mastered the whole curriculum by his thirteenth year. He then studied law in Toulouse and entered a career in the local legal system. He was a counselor of the Court des Aides of Périgueux and, in 1557, he was appointed counselor of the Parlement in Bordeaux (a high court). From 1561 to 1563 he was courtier at the court of Charles IX; he was present with the king at the siege of Rouen (1562). He was awarded the highest honour of the French nobility, the collar of the Order of St. Michael, something to which he aspired from his youth. While serving at the Bordeaux Parliament, he became very close friends with the humanist poet Étienne de la Boétie, whose death in 1563 deeply affected Montaigne. It has been argued that because of Montaigne's "imperious need to communicate," that, after losing Étienne, he began the Essais as his "means of communication;" and that "the reader takes the place of the dead friend."[16]

In a prearranged marriage, Montaigne married Françoise de la Cassaigne. He did not marry her under his own free will and was pressured by family to do so;[citation needed] they had six daughters, though only the second-born survived childhood.

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

| Portals |

In 1571, he retired from public life to the Tower of the Château, his so-called "citadel", in the Dordogne, where he almost totally isolated himself from every social and family affair. Locked up in his library, which contained a collection of some 1,500 works, he began work on his Essais ("Essays"), first published in 1580. On the day of his 38th birthday, as he entered this almost ten-year period of self-imposed reclusion, he had the following inscription crown the bookshelves of his working chamber:

'In the year of Christ 1571, at the age of thirty-eight, on the last day of February, his birthday, Michael de Montaigne, long weary of the servitude of the court and of public employments, while still entire, retired to the bosom of the learned virgins, where in calm and freedom from all cares he will spend what little remains of his life, now more than half run out. If the fates permit, he will complete this abode, this sweet ancestral retreat; and he has consecrated it to his freedom, tranquility, and leisure.’[17]During this time of the Wars of Religion in France, Montaigne, a Roman Catholic, acted as a moderating force,[citation needed] respected both by the Catholic King Henry III and the Protestant Henry of Navarre.

In 1578, Montaigne, whose health had always been excellent, started suffering from painful kidney stones, a sickness he had inherited from his father's family. Throughout this illness, he would have nothing to do with doctors or drugs.[18] From 1580 to 1581, Montaigne traveled in France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, partly in search of a cure, establishing himself at Bagni di Lucca where he took the waters. His journey was also a pilgrimage to the Holy House of Loreto, to which he presented a silver relief depicting himself and his wife and daughter kneeling before the Madonna, considering himself fortunate that it should be hung on a wall within the shrine.[19] He kept a fascinating journal recording regional differences and customs and a variety of personal episodes, including the dimensions of the stones he succeeding in ejecting from his bladder. This was published much later, in 1774, after its discovery in a trunk which is displayed in his tower.[20]

While travelling through Rome in 1581 Montaigne was detained in order to have the text of his Essais examined by Sisto Fabri who served as Master of the Sacred Palace under Pope Gregory XIII. After Fabri examined Montaigne's Essais the text was returned to its author on 20 March, 1581. Montaigne had apologized for references to the pagan notion of "fortuna" as well as for writing favorably of Julian the Apostate and of heretical poets, and was released to follow his own conscience in making emendations to the text.[21]

While in the city of Lucca in 1581, he learned that he had been elected mayor of Bordeaux; he returned and served as mayor. He was reelected in 1583 and served until 1585, again moderating between Catholics and Protestants. The plague broke out in Bordeaux toward the end of his second term in office, in 1585. In 1586, the plague and the Wars of Religion prompted him to leave his château for two years.[18]

Montaigne continued to extend, revise, and oversee the publication of Essais. In 1588 he wrote its third book and also met the writer Marie de Gournay, who admired his work and later edited and published it. Montaigne called her his adopted daughter.[18] King Henry III was assassinated in 1589, and Montaigne then helped to keep Bordeaux loyal to Henry of Navarre, who would go on to become King Henry IV.

Montaigne died of quinsy at the age of 59, in 1592 at the Château de Montaigne. The disease in his case "brought about paralysis of the tongue",[22] and he had once said "the most fruitful and natural play of the mind is conversation. I find it sweeter than any other action in life; and if I were forced to choose, I think I would rather lose my sight than my hearing and voice."[23] Remaining in possession of all his other faculties, he requested mass, and died during the celebration of that mass.[24]

He was buried nearby. Later his remains were moved to the church of Saint Antoine at Bordeaux. The church no longer exists: it became the Convent des Feuillants, which has also disappeared.[25] The Bordeaux Tourist Office says that Montaigne is buried at the Musée Aquitaine, Faculté des Lettres, Université Bordeaux 3 Michel de Montaigne, Pessac. His heart is preserved in the parish church of Saint-Michel-de-Montaigne.

The humanities branch of the University of Bordeaux is named after him: Université Michel de Montaigne Bordeaux 3.

Essais

Main article: Essays (Montaigne)

His fame rests on the Essais, a collection of a large number

of short subjective treatments of various topics published in 1580,

inspired by his studies in the classics, especially Plutarch.

Montaigne's stated goal is to describe humans, and especially himself,

with utter frankness. Montaigne's writings are studied within literary

studies, as literature and philosophy around the world.Inspired by his consideration of the lives and ideals of the leading figures of his age, he finds the great variety and volatility of human nature to be its most basic features. He describes his own poor memory, his ability to solve problems and mediate conflicts without truly getting emotionally involved, his disdain for the human pursuit of lasting fame, and his attempts to detach himself from worldly things to prepare for his timely death. He writes about his disgust with the religious conflicts of his time, reflecting a spirit of skepticism and belief that humans are not able to attain true certainty. The longest of his essays, Apology for Raymond Sebond, contains his famous motto, "What do I know?"

Montaigne considered marriage necessary for the raising of children, but disliked strong feelings of passionate love because he saw them as detrimental to freedom. In education, he favored concrete examples and experience over the teaching of abstract knowledge that has to be accepted uncritically. His essay "On the Education of Children" is dedicated to Diana of Foix.

The Essais exercised important influence on both French and English literature, in thought and style.[26] Francis Bacon's Essays, published over a decade later, in 1596, are usually assumed to be directly influenced by Montaigne's collection, and Montaigne is cited by Bacon alongside other classical sources in later essays.[27]

Montaigne's Influence on Psychology

Though not a scientist, Montaigne made observations on topics in psychology.[28] In his essays, he developed and explained his observations of these topics. His thoughts and ideas covered topics including (but not limited to) thought, motivation, fear, happiness, child education, experience, and human action. Montaigne’s ideas have had an impact on psychology and are a part of psychology’s rich history.Child Education

Child education was among the psychological topics that he wrote about.[28] His essays On the Education of Children, On Pedantry, and On Experience explain the views he had on child education.[29]:61:62:70 Some of his views on child education are still relevant today.[30]

Montaigne’s views on the education of children were opposed to the common educational practices of his day.[29]:63:67He found fault with both what was taught and how it was taught.[29]:62 Much of the education during Montaigne’s time was focused on the reading of the classics and learning through books.[29]:67Montaigne disagreed with learning strictly through books. He believed it was necessary to educate children in a variety of ways.He also disagreed with the way information was being presented to students. It was being presented in a way that encouraged students to take the information that was taught to them as absolute truth. Students were denied the chance to question the information. Therefore, students could not truly learn. Montaigne believed that to truly learn, a student had to take the information and make it their own.

At the foundation Montaigne believed that the selection of a good tutor was important for the student to become well educated.[29]:66 Education by a tutor was to be done at the pace of the student.[29]:67He believed that a tutor should be in dialogue with the student, letting the student speak first. The tutor should also allow for discussions and debates to be had. Through this dialogue, it was meant to create an environment in which students would teach themselves. They would be able to realize their mistakes and make corrections to them as necessary.

Individualized learning was integral to his theory of child education as well. He argued that student combines information he already knows with what is learned and forms a unique prospective on the newly learned information from his previous knowledge.[31]:356 Montaigne also thought that tutors should encourage a student’s natural curiosity and allow them to question things.[29]:68He postulated that a successful student was one that was encouraged to question things and study them for themselves, rather than simply accepting what they heard from the authorities on any given topic. Montaigne believed that a child’s curiosity could serve as an important teaching tool when a child is allowed to explore the things that they are curious about.

Experience was also a key element to learning for Montaigne. Tutors needed to teach students through experience rather than through the mere memorization of knowledge often practiced in book learning.[29]:62:67He argued that students would become passive adults; blindly obeying and lacking the ability to think on their own.[31]:354Nothing of importance would be retained and no abilities would be learned.[29]:62 He believed that learning through experience was superior to learning through the use of books.[30] For this reason he encouraged tutors to educate their students through practice, travel, and human interaction. In doing so, he argued that students would become active learners, who could claim knowledge for themselves.

Montaigne’s views on child education continue to have an influence in the present. Variations of Montaigne’s ideas on education are incorporated into modern learning in some ways. He argued against the popular way of teaching in his day, encouraging individualized learning. He believed in the importance of experience over book learning and memorization. Ultimately, Montaigne postulated that the point of education was to teach a student how to have a successful life by practicing an active and socially interactive lifestyle..[31]:355

Related writers and influence

Thinkers exploring similar ideas include Erasmus, Thomas More, and Guillaume Budé, who all worked about fifty years before Montaigne. Most of Montaigne's Latin quotations are from Erasmus' Adagia, and most critically, all of his quotations from Socrates.Since Edward Capell first made the suggestion in 1780, some scholars believe that Shakespeare was familiar with Montaigne's essays.[32] John Florio's translation of Montaigne's Essais became available to Shakespeare in English in 1603.[33] It is suggested[by whom?] that Montaigne's influence is especially noticeable in Hamlet and King Lear, both in language and in the skepticism present in both plays.[improper synthesis?]

| Of The Caniballes translated by John Florio (1603)

John Florio also translated Montaigne's essay titled ""Of

Friendship"" in 1603. This translated form could have been available to

""William Shakespeare"" and may have had some influence over his

sonnets, which were addressed primarily to a young man. |

The Tempest Act 2, Scene 1 |

| It is a nation, would I answer Plato, that hath no kinde of traffike, no knowledge of Letters, no intelligence of numbers, no name of magistrate, nor of politike superioritie; no use of service, of riches or of povertie; no contracts, no successions, no partitions, no occupation but idle; no respect of kindred, but common, no apparell but naturall, no manuring of lands, no use of wine, corne, or mettle. The very words that import lying, falshood, treason, dissimulations, covetousnes, envie, detraction, and pardon, were never heard of amongst them. How dissonant would hee finde his imaginarie common-wealth from this perfection? | Gonzalo:I' the commonwealth I would by contraries execute all things; for no kind of traffic would I admit; no name of magistrate; letters should not be known; riches, poverty, and use of service, none; contract, succession, bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none; no use of metal, corn, or wine, or oil; no occupation; all men idle, all: and women too, but innocent and pure; no sovereignty...All things in common nature should produce without sweat or endeavour; treason, felony, sword, pike, knife, gun, or need of any engine, would I not have; but nature should bring forth, of it own kind, all foison, all abundance, to feed my innocent people...I would with such perfection govern, sir, To excel the golden age. |

| That The Taste of Goods or Evils Doth Greatly Depend on the Opinion We Have of Them translated by John Florio (1603) | Hamlet Act 2, Scene 1 |

| "Men...are tormented by the opinions they have of things, and not by things themselves" | Hamlet: Why, then, 'tis none to you; for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so: to me it is a prison. |

Much of Blaise Pascal's skepticism in his Pensées has been traditionally attributed to his reading Montaigne.[34]

The English essayist William Hazlitt expressed boundless admiration for Montaigne, exclaiming that "he was the first who had the courage to say as an author what he felt as a man. ... He was neither a pedant nor a bigot. ... In treating of men and manners, he spoke of them as he found them, not according to preconceived notions and abstract dogmas".[35] Beginning most overtly with the essays in the "familiar" style in his own Table-Talk, Hazlitt tried to follow Montaigne's example.[4]

Ralph Waldo Emerson chose "Montaigne; or, the Skeptic" as a subject of one of his series of lectures entitled Representative Men, alongside other subjects such as Shakespeare and Plato. Friedrich Nietzsche judged of Montaigne: "That such a man wrote has truly augmented the joy of living on this Earth".[36]

The American philosopher Eric Hoffer employed Montaigne both stylistically and in thought. In Hoffer's memoir, Truth Imagined, he said of Montaigne, "He was writing about me. He knew my innermost thoughts." The Welsh novelist John Cowper Powys expressed his admiration for Montaigne's philosophy in his books Suspended Judgements (1916) and The Pleasures of Literature (1938). Judith N. Shklar introduces her book Ordinary Vices (1984), "It is only if we step outside the divinely ruled moral universe that we can really put our minds to the common ills we inflict upon one another each day. That is what Montaigne did and that is why he is the hero of this book. In spirit he is on every one of its pages..."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered