OK, let's get to the bottom of this!--Well, hang on your hats again , folks, because these Vegans are not just fooling around and are...well, picky about what they would ingest.

As I read along here I saw something about food from insects...oh, they mean honey...but whatever else too I suppose ( no chocolate covered ants I assume)..

So, your friend the long-winded blogger gives you the low down...and don't say you haven't been warned

Veganism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the vegan diet and philosophy. For notable vegans, see List of vegans.

| Veganism | |

|---|---|

| Description | Elimination of the use of animal products |

| Early proponents | Roger Crab (1621–1680) James Pierrepont Greaves (1777–1842) Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888) Donald Watson (1910–2005) H. Jay Dinshah (1933–2000) |

| Origin of the term | 1 November 1944, with the foundation of the British Vegan Society |

| Notable vegans | |

| List of vegans | |

Distinctions are sometimes made between different categories of veganism. Dietary vegans (or strict vegetarians) refrain from consuming animal products, not only meat but, in contrast to ovo-lacto vegetarians, also eggs, dairy products and other animal-derived substances. The term ethical vegan is often applied to those who not only follow a vegan diet, but extend the vegan philosophy into other areas of their lives, and oppose the use of animals or animal products for any purpose.[1] Another term used is environmental veganism, which refers to the rejection of animal products on the premise that the harvesting or industrial farming of animals is environmentally damaging and unsustainable.[2]

The term vegan was coined in England in 1944 by Donald Watson, co-founder of the British Vegan Society, to mean "non-dairy vegetarian"; the society also opposed the consumption of eggs. In 1951 the society extended the definition of veganism to mean "the doctrine that man should live without exploiting animals," and in 1960 H. Jay Dinshah started the American Vegan Society, linking veganism to the Jain concept of ahimsa, the avoidance of violence against living beings.[3]

Veganism is a small but growing movement. In many countries the number of vegan restaurants is increasing, and some of the top athletes in certain endurance sports – for instance, the Ironman triathlon and the ultramarathon – practise veganism, including raw veganism.[4] Well-planned vegan diets have been found to offer protection against certain degenerative conditions, including heart disease,[5] and are regarded by the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada as appropriate for all stages of the life-cycle.[6] Vegan diets tend to be higher in dietary fibre, magnesium, folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E, iron, and phytochemicals, and lower in calories, saturated fat, cholesterol, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin D, calcium, zinc, and vitamin B12.[7] Because uncontaminated plant foods do not provide vitamin B12 (which is produced by microorganisms such as bacteria), researchers agree that vegans should eat foods fortified with B12 or take a daily supplement (see below).[8]

History

Coining the term vegetarianism (19th century)

Further information: History of vegetarianism

Fruitlands in 1915, an early vegan community in Harvard, Massachusetts

In the 19th century vegetarians who also avoided eggs and dairy products, or avoided using animals for any purpose, were referred to as strict or total vegetarians.[11] There were several attempts in the 19th century to establish strict-vegetarian communities. In 1834 Amos Bronson Alcott (1799–1888), the American transcendentalist and father of the novelist Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888) – opened the Temple School in Boston, Massachusetts, along strict-vegetarian principles, and in England in 1838 James Pierrepont Greaves (1777–1842) opened Alcott House in Ham, Surrey, a community and school that followed a strict-vegetarian diet.[12] In 1844 Alcott founded Fruitlands, a community in Harvard, Massachusetts, that opposed the use of animals for any purpose, including farming, though it lasted only seven months.[13]

Shift toward veganism (early 20th century)

Members of Alcott House were involved in 1847 in forming the British Vegetarian Society.[14] In 1851 an article appeared in the society's magazine about alternatives to leather for shoes, which the International Vegetarian Union cites as evidence of the existence in England of a group who were not only strict vegetarians, but avoided animal products entirely.[15] In 1886 the society published an influential essay, A Plea for Vegetarianism, by the English campaigner Henry Salt (1851–1939), a classics teacher at Eton. Salt promoted vegetarianism as a moral issue, not only as an issue of human health; in his Animals' Rights: Considered in Relation to Social Progress (1892), he was one of the first writers to make the paradigm shift from animal welfare to animal rights.[16] Salt wrote in his 1888 essay that being a vegetarian was a "formidable admission" to make, because "a Vegetarian is still regarded, in ordinary society, as little better than a madman."[17] The essay influenced, among others, Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948), who became a friend of Salt's.[18]

Mahatma Gandhi at the Vegetarian Society in London on 20 November 1931, with Henry Salt sitting to his right.[18]

In November 1931 Mahatma Gandhi addressed a meeting in London of the Vegetarian Society – attended by around 500 members, including Henry Salt – arguing that it ought to promote a meat-free diet as a moral issue, not as an issue of human health.[22] Gandhi had become friends with several vegetarian campaigners, including the human-rights campaigner Annie Besant (1847–1933), the novelist Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) and the physician Anna Kingsford (1846–1888), author of The Perfect Way in Diet (1881). His speech was called "The Moral Basis of Vegetarianism"; Norm Phelps writes that it was a rebuke to members who had focused on its health benefits.[23] Gandhi told the society he had found in his student days in London that vegetarians talked of nothing but food and disease: "I feel that this is the worst way of going about the business. I notice also that it is those persons who become vegetarians because they are suffering from some disease or other – that is, from purely the health point of view – it is those persons who largely fall back. I discovered that for remaining staunch to vegetarianism a man requires a moral basis."[24]

Coining the term vegan, founding of the Vegan Society (1944)

Further information: Vegan Society

In 1935 the Vegetarian Society's journal wrote that the issue of

whether vegetarians ought to eat dairy products and eggs was becoming

more pressing with every year.[21] In July 1943 Leslie Cross, a member of the Leicester Vegetarian Society, expressed concern in its newsletter, The Vegetarian Messenger, that vegetarians were still consuming cow's milk.[25]

He echoed the argument about eggs, that to produce milk for human

consumption the cow has to be separated from her calves soon after their

birth: "in order to produce a dairy cow, heart-rending cruelty, and not

merely exploitation, is a necessity."[26]

Cross was later a founder of the Plant Milk Society, now known as

Plamil Foods, which in 1965 began production of the first widely

distributed soy milk in the Western world.[27]In August 1944 two of the Vegetarian Society's members, Donald Watson (1910–2005) and Elsie "Sally" Shrigley (died 1978), suggested forming a subgroup of non-dairy vegetarians. When the executive committee rejected the idea, they and five others met on 1 November that year at the Attic Club in Holborn, London, to discuss setting up a separate organization.[28] They suggested several terms to replace non-dairy vegetarian, including dairyban, vitan, benevore, sanivore and beaumangeur. Watson decided on vegan, pronounced veegun (/ˈviːɡən/), with the stress on the first syllable. As he put it in 2004, the word consisted of the first three and last two letters of vegetarian, "the beginning and end of vegetarian." He called the new group the Vegan Society. Its first newsletter – priced 2d, or 1/- for a year's subscription – was distributed to 500 people.[29] Since 1994 World Vegan Day has been held every 1 November, the Vegan Society's founding date.[30]

Stepaniak writes that two vegan books appeared in 1946: the Leicester Vegetarian Society published Vegetarian Recipes without Dairy Produce by Margaret B. Rawls in the spring, and that summer the Vegan Society published Vegan Recipes by Fay K. Henderson.[31] In 1951 the Vegan Society broadened its definition of veganism to "the doctrine that man should live without exploiting animals," and pledged to seek an end to the use of animals "for food, commodities, work, hunting, vivisection and all other uses involving exploitation of animal life by man."[32] Leslie Cross, by then the society's vice-president, wrote: "[V]eganism is not so much welfare as liberation, for the creatures and for the mind and heart of man; not so much an effort to make the present relationship bearable, as an uncompromising recognition that because it is in the main one of master and slave, it has to be abolished before something better and finer can be built."[32]

Founding of the American Vegan Society (1960)

Further information: American Vegan Society

The first vegan society in the United States was founded in 1948 by a

nurse and chiropractor, Catherine Nimmo (1887–1985) of Oceano,

California, and Rubin Abramowitz of Los Angeles. Originally from the

Netherlands, Nimmo had been a vegan since 1931, and when the British

Vegan Society was founded she began distributing its newsletter, The Vegan News, to her mailing list within the United States.[33] In 1957 H. Jay Dinshah (1933–2000), the son of a Parsi

from Mumbai, visited a slaughterhouse and read some of Watson's

literature. He gave up all animal products, and on 8 February 1960

founded the American Vegan Society (AVS) in Malaga, New Jersey. He

incorporated Nimmo's society and explicitly linked veganism to the

concept of ahimsa, a Sanskrit word meaning "non-harming." The AVS called the idea "dynamic harmlessness," and named its magazine Ahimsa.[34] Joanne Stepaniak writes that two years later, in 1962, the word vegan was independently published for the first time, in the Oxford Illustrated Dictionary; the dictionary defined it as "a vegetarian who eats no butter, eggs, cheese or milk."[35]From marginal to mainstream (1980s–today)

Further information: List of vegans

Dean Ornish is one of a number of physicians who recommend a low-fat plant-based diet.

From the 1990s onwards, their arguments about the health benefits, together with growing concern for the welfare of animals raised in factory farms, led to an increased interest in veganism. In January 2011 the Associated Press (AP) reported that the vegan diet was moving from marginal to mainstream in the United States, with vegan books such as Skinny Bitch (2005) becoming best sellers, and several celebrities exploring vegan diets: "Today's vegans are urban hipsters, suburban moms, college students, even professional athletes." According to the AP, over half the 1,500 chefs polled in 2011 by the National Restaurant Association included vegan entrees in their restaurants, and chain restaurants began to mark vegan items on their menus.[38]

The first Vegetarian Butcher shop – selling vegan and vegetarian "mock meats" – opened in the Netherlands in 2010; as of September 2011 there were 30 branches in the Netherlands and Belgium.[39] In February 2011 Europe's first "all vegan" supermarket, Vegilicious, opened in Dortmund, Germany; elsewhere in Germany, Berlin has become known for its veganism and a "Vegan Spring" food fair has been held annually in Hanover since 2010.[40]

Former US president Bill Clinton adopted a vegan diet in 2010 after cardiac surgery, eating legumes, vegetables and fruit, together with a daily drink of almond milk, fruit and protein powder; his daughter Chelsea was already a vegan.[41] Oprah Winfrey followed a vegan diet for 21 days in 2008, and in 2011 asked her 378 production staff to do the same for one week.[42] In 2009 Dr. Mehmet Oz began advising his viewers to go vegan for 28 days.[43] In November 2010 Bloomberg Businessweek reported that a growing number within the business community were following a vegan diet, including William Clay Ford, Jr., Joi Ito, John Mackey, Russell Simmons, Biz Stone, Steve Wynn and Mortimer Zuckerman. The boxer Mike Tyson also announced that he had switched to a vegan diet.[44] In August 2011 Dr. Sanjay Gupta, CNN's chief medical correspondent, said in his documentary The Last Heart Attack that T. Colin Campbell's The China Study (2005), which cautions against the consumption of any animal fat or animal protein, had changed the way people all over the world eat, including Gupta himself.[45]

The issue that divided the early vegetarians – whether avoiding animal products was a moral issue, or for the most part a health one – persists. Dietary vegans avoid eating or drinking anything that contains an animal product (no meat, fish, eggs or dairy products) out of concern for human health or animal welfare, but may continue to use animal products in clothing, toiletries and other areas.[46] Against this, ethical vegans see veganism as a philosophy. They reject the commodity or property status of animals, and refrain entirely from using them or products derived from them; they will not use animals for food, clothing, entertainment or any other purpose.[47]

Demographics

Surveys in the United States suggest that between 0.5 and three percent (one to six million) in that country are vegan. In 1996 three percent said they did not use animals for any purpose.[48] A 2006 Harris Interactive poll suggested that 1.4 percent were dietary vegans, a 2008 survey for the Vegetarian Resource Group (VRG) reported 0.5 percent, a 2009 VRG survey said one percent – two million out of a population of 313 million, or one in 150 – and a 2012 Gallup poll reported two percent.[49]In Europe, The Times estimated in 2005 that there were 250,000 vegans in the UK, in 2006 The Independent estimated 600,000, and in 2007 a British government survey identified two percent as vegan.[50] The Netherlands Association for Veganism estimated there were 16,000 vegans in the Netherlands as of 2007, around 0.1 percent of the population.[51]

Animal products

Avoidance

Further information: Animal product and Rendering (food processing)

Ethical vegans entirely reject the commodification

of animals. The Vegan Society in the UK will only certify a product as

vegan if it is free of animal involvement as far as possible and

practical, including animal testing.[52]An animal product is any material derived from animals, including meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, dairy products, honey, fur, leather, wool, and silk. Other commonly used, but perhaps less well-known, animal products are beeswax, bone char, bone china, carmine, casein, cochineal, gelatin, isinglass, lanolin, lard, rennet, shellac, tallow, whey, and yellow grease. Many of these may not be identified in the list of ingredients in the finished product.[53]

Ethical vegans will not use animal products for clothing, toiletries, or any other reason, and will try to avoid ingredients that have been tested on animals. They will not buy fur coats, cars with leather in them, leather shoes, belts, bags, wallets, woollen jumpers, silk scarves, camera film, bedding that contains goose down or duck feathers, and will not use certain vaccines; the production of the flu vaccine, for example, involves the use of chicken eggs. Depending on their economic circumstances, vegans may donate items made from animal products to charity when they become vegan, or use them until they wear out. Clothing made without animal products is widely available in stores and online. Alternatives to wool include acrylic, cotton, hemp, rayon and polyester. Some vegan clothes, in particular shoes and leather alternatives, are made of petroleum-based products, which has triggered criticism because of the environmental damage associated with production.[54]

Milk and eggs

Further information: Dairy product and Egg (food)

One of the main differences between vegan and vegetarian diets is

that vegan diets exclude both eggs and dairy products (such as animal

milk, cheese, butter and yogurt). Ethical vegans state that the

production of eggs and dairy causes animal suffering and premature

death. For example, in both battery cage and free-range egg production, most male chicks are culled at birth because they will not lay eggs, and there is no financial incentive for a producer to keep them.[55]To produce milk from dairy cattle, dairy cows are kept almost permanently pregnant through artificial insemination to prolong lactation. Male calves are slaughtered at birth, sent for veal production, or reared for beef. Female calves are separated from their mothers a few days after birth and fed milk replacer, so that the cow's milk is retained for human consumption.[56] After about five years, once the cow's milk production has dropped, they are considered "spent" and sent to slaughter for hamburger meat and their hides. A dairy cow's natural life expectancy is about twenty years.[57] The situation is similar with goats and their kids.[58]

Honey and other insect products

Further information: Honey bee and Beekeeping

There is disagreement among vegan groups about the extent to which

products from insects must be avoided. Some vegans view the consumption

of honey as cruel and exploitative, and modern beekeeping a form of

enslavement.[59] Once the honey (the bees' natural food store) is harvested, it is common practice to substitute it with sugar or corn syrup

to maintain the colony over winter. Neither the Vegan Society nor the

American Vegan Society considers the use of honey, silk or other insect

products to be suitable for vegans, while Vegan Action and Vegan

Outreach regard it as a matter of personal choice.[60] Agave nectar is a popular vegan alternative to honey.[61]Vegan diet

Common dishes and ingredients

- Further information: Vegan recipes

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

Plant milk, ice-cream and cheese

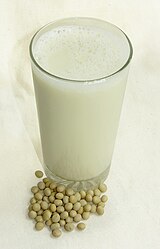

Plant cream and plant milk – such as soy milk, almond milk, grain milk (oat milk and rice milk) and coconut milk – are used instead of cows' or goats' milk. The most widely available are soy and almond milk. Soy milk provides around 7 g of protein per cup (250 ml or 8 fluid ounces). Almond milk has fewer calories but less protein.[64]

Like animal milk and meat, soy milk is a complete protein, meaning that it contains all the essential amino acids and can be relied upon entirely for protein intake.[62] Soy milk alone should not be used as a replacement for breast milk for babies; babies who are not breastfed need commercial infant formula, which is normally based on cow's milk or soy (the latter is known as soy-based infant formula or SBIF).[65]

Popular plant-milk brands include Dean Foods' Silk soy milk and almond milk, Blue Diamond's Almond Breeze, Taste the Dream's Almond Dream and Rice Dream, Plamil Foods' Organic Soya and Alpro's Soya. Vegan ice-creams based on plant milk include Tofutti, Turtle Mountain's So Delicious, and Luna & Larry’s Coconut Bliss.[66]

Cheese analogues are made from soy, nuts and tapioca. Vegan cheeses like Chreese, Daiya, Sheese, Teese and Tofutti can replace both the taste and meltability of dairy cheese.[67] Nutritional yeast is a common cheese substitute in vegan recipes.[68] Cheese substitutes can be made at home, using recipes from Joanne Stepaniak's Vegan Vittles (1996), The Nutritional Yeast Cookbook (1997), and The Uncheese Cookbook (2003), and Mikoyo Schinner's Artisan Vegan Cheese (2012).[69] One recipe for vegan brie involves combining cashews, soy yogurt and coconut oil.[70] Butter can be replaced with a vegan margarine such as Earth Balance.[71]

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered