Magazine

A fascination with gangsters

- 22 September 2015

- Magazine

Studiocanal

Studiocanal

The film Legend, telling the story of the Kray twins, has broken box office records since its release earlier this month. Johnny Depp has played notorious Boston gangster Whitey Bulger. But what is it about gangsters' life stories that continues to fascinate audiences?

Warning: This piece contains spoilers

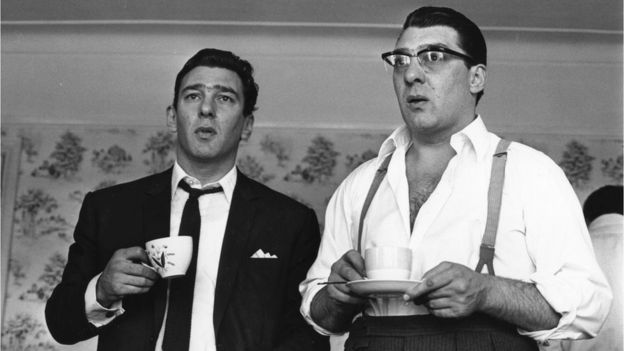

"I am not going to waste words on you," said Justice Melford Stevenson as he sentenced Ronnie and Reggie Kray to life imprisonment. "In my view society has earned a rest from your activities."

The judge's disdain at the end of their murder trial in 1969 reflects an official view of gangsters. They hurt and kill for money. They torture rivals. They steal. They sell drugs. They traffic people for sex. They terrorise neighbourhoods.

But, contrary to the judge's wishes, leaders of organised crime need not fear obscurity. Hundreds of films and books have been made and written about their exploits.

The hunger for information shows no sign of letting up with Legend, a Krays biopic starring Tom Hardy as both brothers, taking more than £5m in its opening weekend. This is the biggest figure for a September opening and the biggest for a British production with an 18 certificate.

Warner Brothers

Warner Brothers

Black Mass, starring Johnny Depp as the Boston gangster James "Whitey" Bulger, has opened in the US and is out soon in the UK. Classics like the Godfather trilogy, Goodfellas, Angels With Dirty Faces, Scarface (two versions) and the Untouchables continue to fascinate, despite showing violence, intimidation and abuse.

What is it that makes gangsters at once so appalling and appealing?

"There's something immensely aspirational about it - this sense that they can do anything," says David Wilson, professor of criminology at Birmingham City University. "They take risks that we would never take in real life. Often there's a good-looking actor playing the lead. They look cool. They wear clothes that are fashionable."

There's also nostalgia - the Krays' trial and imprisonment came at the end of the 1960s, London's "swinging" decade. They mixed with celebrities, politicians and society figures before their downfall. Most of those involved or affected by the Krays' reign are no longer active or alive, so a sheen of legend attaches itself more easily.

The Krays

Getty Images

Getty Images- Identical twins, Ronnie and Reggie, born in 1933 and raised in East London; they became Britain's most notorious gangsters in 1950s and 1960s

- Involved in protection rackets, illegal gambling, arson and murder; attracted wider fame in 1964 when a newspaper (unsuccessfully) claimed Ronnie Kray was having an affair with a peer, Lord Boothby

- The twins were arrested in 1968, tried and convicted for separate murders - both were sentenced to life imprisonment

- Ronnie died in jail and Reggie after a brief release when suffering from cancer

Films about criminals have been popular for more than a century. DW Griffith's The Musketeers of Pig Alley, released in 1912, is regarded by many critics as the world's first gangster movie. Without revealing the plot, it's fair to say its main villain doesn't really get his comeuppance.

US academics Robert Bieber and Robert Kelly have written of gangsterism in popular culture in this era as a parallel of the American Dream - the poor managing to establish an exalted position in society and great wealth by illegal means. For those denied opportunities, they become criminal class warriors.

ALAMY

ALAMY

Wilson is sceptical of this idea, though, arguing that an interest in gangsters is less about their origins than their destination in life. "You could get a film about [Metropolitan Police Commissioner] Bernard Hogan-Howe, who came from quite a poor background, but no-one would want to make that. There's something about good guys that doesn't resonate with a cinema-going audience. They won't take the same level of risk or behave outside any moral compass."

The films of the 1910s and 1920s were seen by many to glamorise crime. So theHays Code, setting out moral guidelines for Hollywood in 1930, stipulated that the "sympathy of the audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin".

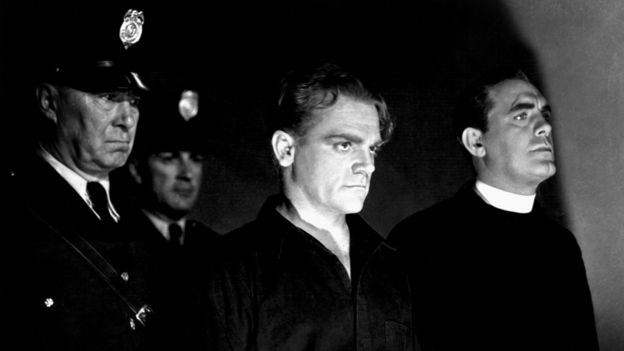

Directors used their ingenuity to include some ambiguity while ostensibly following the code. The 1932 film Scarface, at the time seen as highly violent, had the subtitle The Shame of the Nation. With its whiff of excitement, it's debatable whether this discouraged or encouraged people to watch. In 1938's Angels With Dirty Faces, James Cagney goes to the electric chair, although there is no sense of remorse.

ALAMY

ALAMY

Simple morality and gangster films had an uneasy relationship even before the code's demise in the mid-1960s. "Although movie viewers expect criminals to fail which means prison or death," say Bieber and Kelly, "the bad guys are seen somewhat sympathetically as victims of circumstances as much as they are perceived as psychopaths or social misfits."

This theme continues in Michael Corleone, the main character in the Godfather Trilogy, released from 1972 to 1990, pulled into running his Mafia family's operations and becoming gradually more brutal. "I didn't see him as a gangster," Al Pacino, who played Corleone, has said. "I felt his power was his enigmatic quality."

ALAMY

ALAMY

Legend's director, Brian Helgeland, has spoken of the need to humanise Reggie Kray, in contrast to his brother, who was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic in 1979. The film, narrated from the point of view of Reggie's wife Frances, shows his decline after her suicide.

But films struggle against time constraints when showing people's lives, often restricted to their most exciting events.

"You see these people at a distance," says writer and broadcaster Antony Earnshaw. "A lot of audiences don't want to see the truth of what these people did. If you put that on screen, they are repulsed by it. They want to believe in the legend and not the truth. Unless you grew up in 1960s Bethnal Green, how can you ever know what the Krays were like?"

"Extreme acts" of good and evil are what attract people, Earnshaw argues. The Krays were known for generosity towards their friends, while their enemies experienced violence.

ALAMY

ALAMY

There are broadly two types of gangster films - the fictional and those based on real stories. The Krays and Black Mass are both among the latter.

These involve a "fine balance" between entertaining audiences and showing the reality, says Earnshaw. This is particularly so as many people who knew Bulger's victims, and to a lesser extent those of the Krays, will still be around.

The Krays were themselves fans of classic US gangster movies and were said to base some of their mannerisms on those of actors like Cagney, Spencer Tracey and Humphrey Bogart. They seem to inhabit a more glamorous world than most. Money, fast cars, sex: films continue to show a lot of the upside. "There's still a romanticisation of the gangster," says Earnshaw.

Gangsters are often shown as colourful characters, from Robert De Niro's portrayal of Chicago bootlegger Al Capone in The Untouchables to the assortment of East End villains to be found in Guy Ritchie's Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels.

There is a sense of honour among many screen gangsters, particularly "omerta" - the mafia's understanding that all members of an organisation maintain silence about its activities, especially when the police are involved.

Whitey Bulger, a prominent figure in Boston's organised crime scene from the 1970s to the mid-1990s, was found guilty in 2013 of 11 murders. He was sentenced two two life terms, plus five years. Ronnie Kray died in 1995 and Reggie Kray in 2000.

ALAMY

ALAMY

Where the ugly reality of gangsters' violence intrudes it can still be shocking, even in the context of a film about them. In Goodfellas, released almost exactly 25 years ago, Joe Pesci's Tommy glasses a restaurateur who asks him to pay the bill. Tommy kills another man, after he mocks his previous career as a shoe-shine boy while standing in the same bar. He punches him repeatedly, while an associate kicks him. Tommy blames the death on "disrespect".

"It's that mentality that frightens me, the way they can act so suddenly in this way," says Earnshaw. "You must never believe that these people are your friends."

More from the Magazine

Getty Images

Getty Images

The Manson case involved drugs, orgies and cults, three concerns shared by parents of children growing up in the "free love" atmosphere of the 1960s. It also came at a time of intense divisions in the US over civil rights, race and the Vietnam War.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

Magazine

Kissed by a giraffe

- 23 September 2015

- Magazine

Struggling to survive

- 23 September 2015

- Magazine

The kidnap machine

- 22 September 2015

- Magazine

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please leave a comment-- or suggestions, particularly of topics and places you'd like to see covered